In geophysical modeling, we often quantify uncertainty using different statistics and probability tools, such as probability distributions, statistical estimators, and geostatistical realizations. For example, the uncertainty associated with the prediction of porosity and fluid saturation from seismic data can be represented by the joint probability distributions of porosity and fluid saturation at each location in the reservoir, by a set of statistical estimations such as the mean, the maximum a posteriori estimate, the confidence interval, and the variance, or by an ensemble of multiple realizations obtained by sampling the probability distribution. In general, it is always possible to build the most‐likely model of the properties of interest from these statistics and probability tools and present the solution in a deterministic form. For example, we can compute the most‐likely value of the probability distribution of porosity and fluid saturation at each location in the reservoir. However, subsurface models are often highly uncertain owing to the lack of direct measurements, the limited quality and resolution of the available geophysical data, the approximations in the physical models, and the natural variability and heterogeneity of subsurface rocks. Therefore, the uncertainty of the predictions should always be considered in any decision‐making process associated with subsurface models.

In this chapter, we review the main concepts of probability and statistics. These results are used in the following chapters to build mathematical methodologies for reservoir modeling, such as geostatistical simulations and inverse methods.

In this review, E represents a generic event and P ( E ) represents its probability. For example, E might represent the occurrence of hydrocarbon sand in a reservoir and P ( E ) the probability of finding hydrocarbon sand at a given location.

Probability theory is based on three axioms:

1 The probability P(E) of an event E is a real number in the interval [0, 1]: (1.1)

2 The probability P(S) of the sample space S is 1:(1.2)

3 If two events, E1 and E2, are mutually exclusive, i.e. E1 ∩ E2 = ∅ (in other words, if the event E1 occurs, then the event E2 does not occur and if the event E2 occurs, then the event E1 does not occur), then the probability of the union E1 ∪ E2 of the two events, i.e. the probability of one of two events occurring, is the sum of the probabilities of the two events P(E1) and P(E2): (1.3)

The axioms in Eqs. (1.1)–(1.3) are the foundations of probability theory. Based on these axioms, the probability of the complementary event  i.e. the probability that the event E does not occur, is given by:

i.e. the probability that the event E does not occur, is given by:

(1.4)

since  . From the axioms, we can also derive that the probability of the union of two generic events, not necessarily mutually exclusive, is:

. From the axioms, we can also derive that the probability of the union of two generic events, not necessarily mutually exclusive, is:

(1.5)

where P ( E 1∩ E 2) is the probability that both events occur. For mutually exclusive events, the intersection of the two events is the empty set ( E 1∩ E 2= ∅), and the probability of the intersection is P ( E 1∩ E 2) = 0; therefore, Eq. (1.5)reduces to the third axiom (Eq. 1.3). The result in Eq. (1.5)can be proven using set theory and the three axioms. The probability P ( E 1∩ E 2) is generally called joint probability and it is often indicated as P ( E 1, E 2).

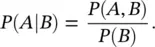

A fundamental concept in probability and statistics is the definition of conditional probability, which describes the probability of an event based on the outcome of another event. In general, the probability of an event E can be defined more precisely if additional information related to the event is available. For example, seismic velocity depends on a number of factors, such as porosity, mineral volumes, and fluid saturations. If one of these factors is known, then the probability of seismic velocity can be estimated more precisely. For instance, if the average porosity of the reservoir is 0.30, it is more likely that the seismic velocity will be relatively low, whereas if the average porosity of the reservoir is 0.05, then it is more likely that the seismic velocity will be relatively high. This idea can be formalized using the concept of conditional probability. Given two events A and B , the conditional probability P ( A ∣ B ) is defined as:

(1.6)

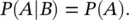

Two events A and B are said to be independent if the joint probability P ( A , B ) is the product of the probability of the events, i.e. P ( A , B ) = P ( A ) P ( B ). Therefore, given two independent events A and B , the conditional probability P ( A ∣ B ) reduces to:

(1.7)

This means that the probability of A does not depend on the outcome of the event B . For a more detailed description of probability theory, we refer the reader to Papoulis and Pillai (2002).

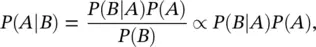

In many practical applications, calculating the joint probability P ( A , B ) in the definition of the conditional probability ( Eq. 1.6) is prohibitive; for example, owing to the lack of data. A common tool to estimate conditional probabilities is Bayes' theorem. This result expresses the conditional probability P ( A ∣ B ) as a function of the conditional probability P ( B ∣ A ), which might be easier to calculate in some applications.

Bayes' theorem states that the conditional probability P ( A ∣ B ) is given by:

(1.8)

where P ( A ) is the probability of A , P ( B ∣ A ) is the probability of the event B given the event A , and P ( B ) is the probability of B . The term P ( A ) is called the prior probability of A since it measures the probability before considering additional information associated with the event B . The term P ( B ∣ A ) is the likelihood function of the event B to be observed for each possible outcome of the event A . The term P ( B ) represents the marginal probability of the event B and it is a normalizing constant to ensure that P ( A ∣ B ) satisfies the axioms. The resulting conditional probability P ( A ∣ B ) is also called the posterior probability of the event A , since it is computed based on the outcome of the event B .

Читать дальше

i.e. the probability that the event E does not occur, is given by:

i.e. the probability that the event E does not occur, is given by:

. From the axioms, we can also derive that the probability of the union of two generic events, not necessarily mutually exclusive, is:

. From the axioms, we can also derive that the probability of the union of two generic events, not necessarily mutually exclusive, is: