A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

www.wiley.com/go/wessells/urologic A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Management

Non‐Operative

Traditionally, penetrating trauma has been managed with surgical exploration. However, there has been a shift toward more conservative management of trauma patients due to the improvements in imaging, interventional radiology, and resuscitation techniques. For hemodynamically stable patients, NOM with close patient observation should be offered as first‐line therapy [25].

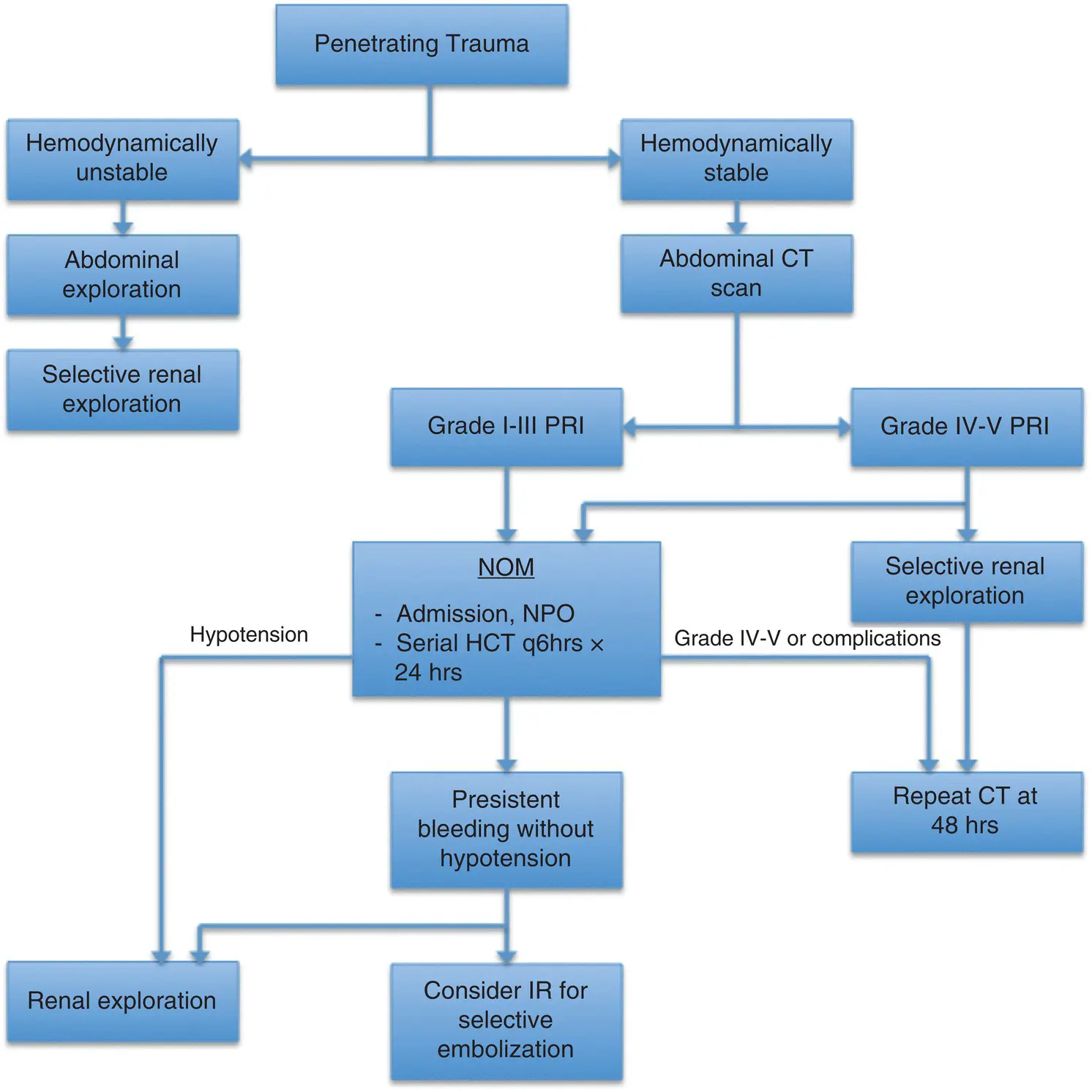

Although there is no consensus algorithm for NOM and there is significant institutional variance, NOM generally comprise of bedrest, strict hemodynamic monitoring in a critical care unit, and serial hematocrit (HCT) checks. If patients are hemodynamically stable with down‐trending HCTs, they should be resuscitated with blood products. The presence of active bleeding on imaging, combined with transfusion requirement or hemodynamic instability, indicate that interventional radiology should be consulted for selective embolization. For patients with urinary extravasation, ureteral stenting should be considered, although optimal timing for stenting (early vs. late) is not currently known. We propose one management strategy in Figure 2.2. NOM, however, should not be equated to non‐interventional management. Rather, NOM should be viewed as an algorithmic approach with stepwise escalation of intervention based on patient dynamics (see Figure 2.3).

For renal injuries, the site of the wound, hemodynamic stability, and diagnostic imaging (grade of injury) are the main determinants for intervention. Although higher‐grade injuries (Grade IV and V) are more likely to require surgical exploration, with careful selection and staging, patients with PRI may be offered a trial of expectant management.

In one series, 54% of stab wounds were successfully managed non‐operatively, with only 3% of patients requiring exploration for delayed bleeding [31]. Another series found that stab wounds were more likely to be successfully managed with NOM if the site of abdominal wound penetration is posterior to the anterior axillary line [32].

PRI from low‐velocity GSWs can be managed with NOM. In one large series, approximately 30% of gunshot PRIs were successfully managed with observation [33]. As there is also a shift toward selective NOM for gunshot abdominal trauma wounds, there may be a larger impetus for NOM in patients with PRI who would not otherwise undergo surgical exploration [34].

Figure 2.2 Proposed Proposed treatment algorithm. CT, computed tomography; HCT, hematocrit; IR, interventional radiology; NOM, non‐operative management; NPO nothing by mouth; PRI, penetrating renal injury.

One quandary has been the management of suspected renal trauma in patients without pre‐operative CT imaging. Data suggests that even if patients are undergoing surgical exploration for associated non‐urologic injuries, renal exploration is not always necessary. The only absolute indication for renal exploration is a pulsatile or expanding retroperitoneal hematoma. Stable retroperitoneal hematomas should not be explored [24]. Obvious urinary leakage from a penetrating mechanism requires evaluation to exclude a renal pelvis or ureteral injury (see Figure 2.4). In one large series of patients undergoing exploratory laparotomy for renal GSWs, 56% of patients did not need renal exploration and renal exploration was associated with a 50% nephrectomy rate [35]. If patients undergo emergent laparotomy without imaging and a stable zone II (retroperitoneal flank) hematoma is not explored, they should receive appropriate renal imaging once stable, in order to evaluate the extent of the injury.

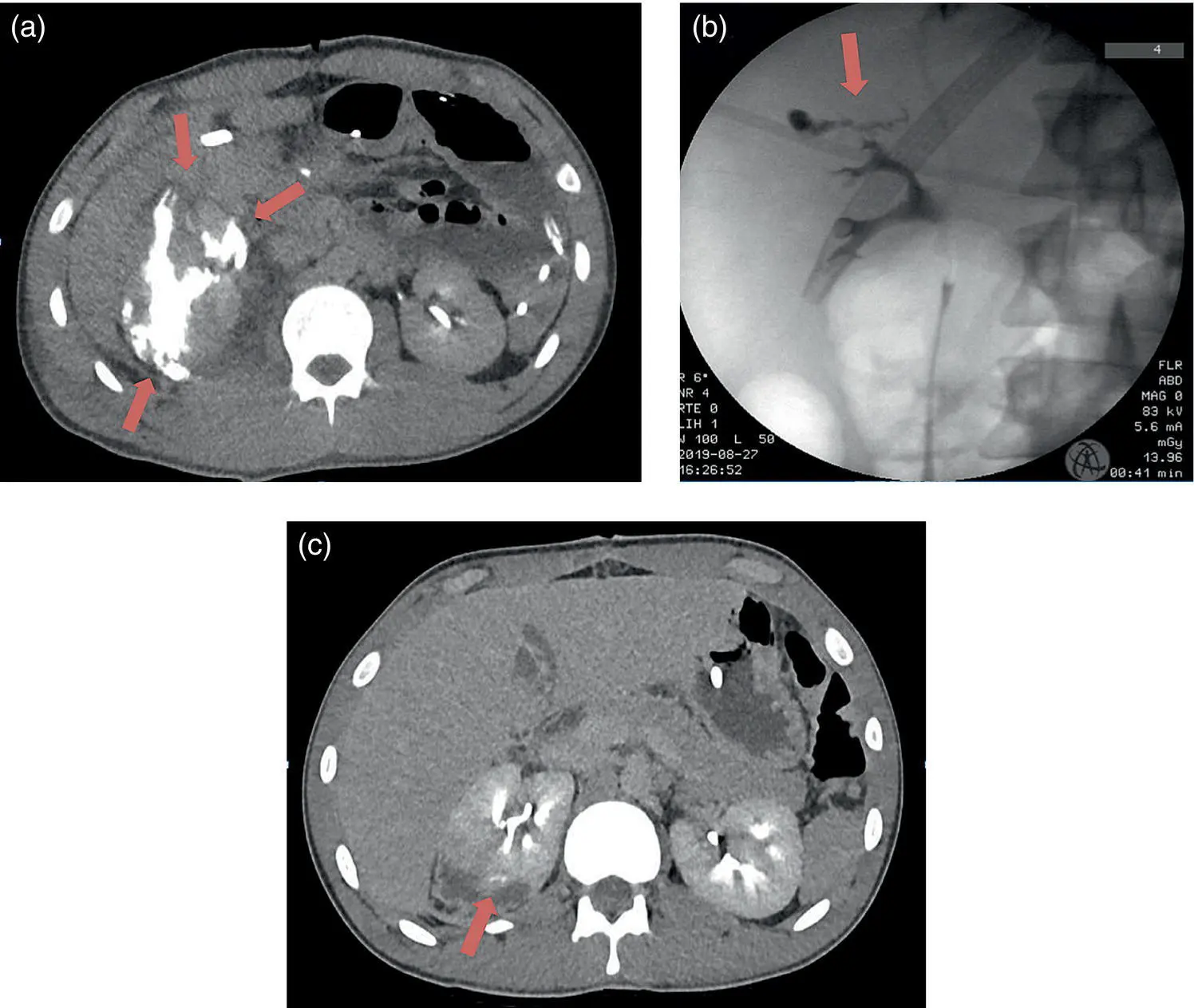

Figure 2.3 Twenty‐one‐year‐old male who sustained a GSW to the abdomen. He had a grade IV right PRI, with injuries to the liver and duodenum. (a) CT demonstrates a significant urine leak on initial delayed phase imaging. (b) He was taken to the operating room for retrograde pyelogram and ureteral stenting. Pyelogram demonstrates contrast extravasation from the middle calyx. Arrow depicts area of contrast extravasation. (c) Repeat CT scan with delayed phase imaging at two weeks demonstrates improved, but persistent contrast extravasation. He was taken to the operating room six weeks after ureteral stenting where retrograde pyelogram demonstrated complete healing of his collecting system and his stent was removed.

Source: courtesy of Jonathan Wingate, MD.

Operative

Operative management of PRI is not as nuanced as NOM – an unstable patient, unresponsive to resuscitation, requires immediate surgical exploration. Surgical exploration is traditionally performed via a midline transabdominal approach. These cases are often performed in conjunction with trauma surgeons, as the rates of concomitant non‐GU organ injuries are very high [8, 36].

Prior to exploring a zone II hematoma, the surgeon should ensure there is a contralateral kidney if no pre‐operative imaging was obtained. This can be performed by manual palpation of the contralateral kidney or a single shot urogram (2 ml/kg of IV contrast followed by a KUB at 10 minutes).

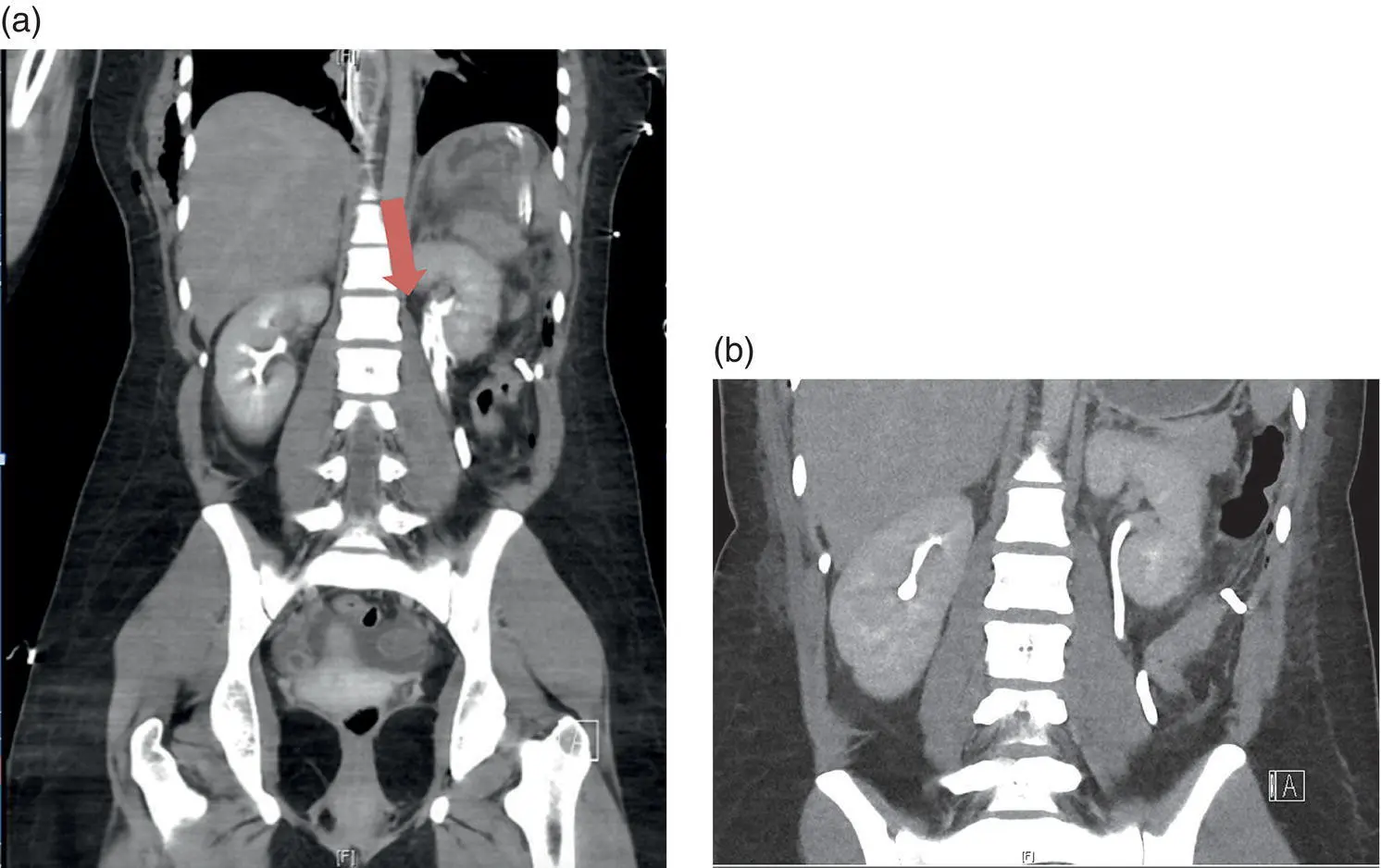

Figure 2.4 Twenty‐five‐year‐old female who sustained multiple stab wounds with a machete. (a) CT scan demonstrates contrast extravasation from the left collecting system. Intra‐operatively, she was noted to have a 1.5 cm renal laceration in the inferior pole. There was active urine extravasation from the wound. A renorrhaphy was performed. She also had injuries to the small bowel and right chest. (b) CT performed 48 hours after renorrhaphy demonstrates resolution of the urine leak.

Source: courtesy of Jonathan Wingate, MD.

Principles of damage control surgery are abbreviated operation, intensive care resuscitation, and definitive surgery. For penetrating trauma, if there is concern for active bleeding at time of laparotomy, source control should be obtained. If there is an expanding zone II hematoma consistent with active renal bleeding, this should be explored. However, for non‐expanding hematomas, if the patient is unstable, four‐quadrant packing with temporary abdominal closure may be performed in order to allow for resuscitation.

There are two surgical approaches to the kidney – medial or lateral. In the medial approach, the renal vessels are isolated prior to renal exploration as early vascular control may decrease nephrectomy rates and blood loss during surgery [37]. The retroperitoneum is incised over the aorta superior to the inferior mesenteric artery and medial to the inferior mesenteric vein. The anterior surface of the aorta is explored until the left renal vein is encountered crossing anteriorly over the aorta. Vessel loops are then placed around the renal hilum and early vascular control is obtained. The kidney is then exposed by incising the peritoneum lateral to the colon and mobilizing the peritoneum off Gerota's fascia. This approach takes longer and may be difficult in the setting of large hematomas.

In cases of active hemorrhage or an unstable patient, one may not have time to get proximal renal vascular access. For rapid exposure, the kidney can be approached laterally – the retroperitoneum lateral to the kidney is opened and the kidney is delivered into the operative field. Manual compression of the renal parenchyma can help tamponade the bleeding. The hilum can also be manually compressed then a vascular clamp is applied. For significant bleeding, more proximal control can be temporarily obtained through digital compression of the aorta at the diaphragmatic hiatus or with the use of a padded Richardson retractor [38].

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.