A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

www.wiley.com/go/wessells/urologic A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Injury from explosions are classified into: (i) primary BI due to the interaction of the blast wave with gas‐filled structures; (ii) secondary BI due to ballistic trauma resulting from fragmentation wounds from the explosive device or the environment; (iii) tertiary BI due to displacement of the victim or environmental structures, which are largely blunt injuries; and (iv) quaternary BI or burns, toxins, and radiation contamination [17]. Most primary BI do not result in surviving causalities because these patients would have been so close to the blast epicenter that they likely sustained lethal injuries. The pressure wave caused by blasts cause damage primarily to gas‐containing organs, such as the lung; the kidneys are remarkably resilient to the pressure effects of blasts, although renal pelvis injuries have been documented [18]. The kidneys are mainly injured by the secondary and tertiary mechanisms. The PRI from blasts have pathophysiology similar to more common injury patterns, such as GSW. Although these fragments are often much smaller than bullets, they may cause more tissue damage due to the sheer number of fragments and because the velocity of these fragments can be over twice that of a rifle.

Anatomy

It is imperative to have a sound understanding of renal anatomy, as it is foundational for understanding associated injury patterns, surgical approach/reconstruction, and comprises the basis of non‐operative management (NOM). The kidneys are paired retroperitoneal organs extending from vertebral levels T12 to L3. From deep to superficial, the layers surrounding the kidney are as follows: renal capsule, peri‐renal fat, renal fascia (Gerota's fascia), and para‐renal fat. Both Gerota's fascia and the renal capsule are responsible for tamponade of renal hematomas and they are both critical layers for renorrhaphy. The vascular supply consists of one main renal artery and vein, although about 25% of kidneys have accessory vessels. The internal structure can grossly be divided into the renal parenchyma and collecting system. The latter is comprised of minor and major calyces that coalesce into the renal pelvis. This distinction between the parenchyma and collecting system is important in renal injury grading ( Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 AAST Renal injury classification, revised in 2018.

| Grade I | Contusion or nonexpanding subcapsular hematoma |

| Grade II | Nonexpanding perirenal hematoma |

| <1 cm cortical laceration without urinary extravasation | |

| Grade III | Cortical laceration >1 cm without urinary extravasation |

| Any injury in the presence of a kidney vascular injury or active bleeding contained within Gerota's fascia | |

| Grade IV | Laceration into collecting system |

| Segmental renal artery or vein injury | |

| Active bleeding beyond Gerota's fascia | |

| Segmental or complete kidney infarction due to vessel thrombosis without active bleeding | |

| Grade V | Main renal artery or vein laceration or hilar avulsion |

| Devascularized kidney with active bleeding | |

| Shattered kidney with loss of identifiable parenchymal renal anatomy |

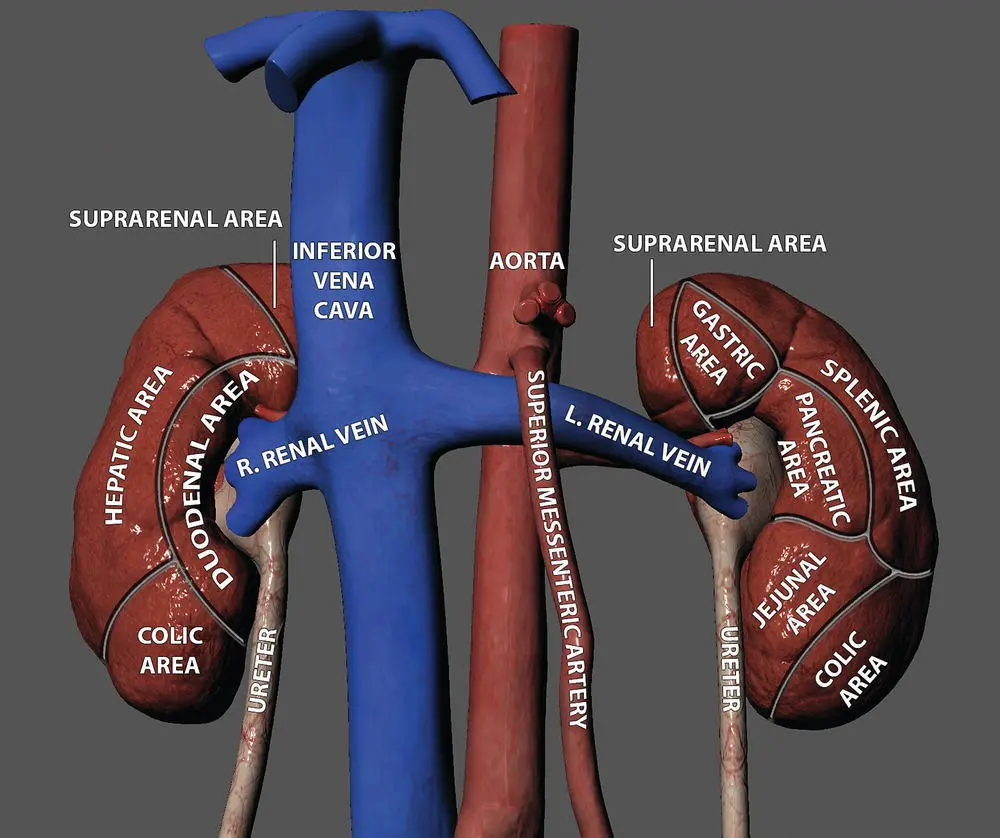

Figure 2.1 The kidneys and their association with adjacent organs.

Source: figure courtesy of Daniel Burke, University of Washington.

The diaphragm, 11th and 12th ribs, quadratus lumborum, and psoas major surround both kidneys. Anteriorly, the right kidney is associated with the liver, duodenum, and right colic flexure; the left kidney is associated with the spleen, stomach, pancreas, left colic flexure, and jejunum ( Figure 2.1). Even with the safeguards of their retroperitoneal location, they are susceptible to penetrating trauma and it is due to their close anatomical relationship with other organs that isolated PRI is rare.

Evaluation

The initial evaluation and management of trauma patients has been standardized according to set protocols with the development of the Advance Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines. Thus, the initial management of the trauma patient has often been completed by the trauma team prior to the involvement of a urologist [19, 20]. Vitals sign monitoring is imperative in patients with PRI, as patient stability dictates management.

For suspected renal trauma, the evaluation should include a thorough history and physical examination to evaluate for penetrating entry and exit wounds, flank ecchymosis, rib fractures, and gross hematuria. In addition to standard laboratory testing, a urinalysis should be obtained to evaluate for microscopic hematuria – defined as three or more red blood cells per high power field. Hematuria is the best indicator of significant renal trauma; however, it is not a sensitive marker, as up to 20.8% of patients with renal trauma lack hematuria [21, 22].

Imaging

The goals of imaging are to grade the renal injury, identify injuries to other organs, and demonstrate the presence of a functioning contralateral kidney should operative management be necessary. The stability of the patient determines the initial imaging; unstable patients cannot obtain computed tomography (CT) scans if they require immediate intervention and the kidneys and retroperitoneum can be assessed in the operating room at time of laparotomy. In military trauma, due to forward deployment of combat support hospitals and the technological progression of expeditionary medicine, CT capabilities are available in war zones and the imaging principles remain congruent with civilian trauma [23].

All stable patients with penetrating abdominal trauma should get diagnostic imaging with IV contrast enhanced CT. To fully evaluate and stage renal trauma ( Table 2.1), the American Urological Association (AUA) and European Association of Urology (EAU) recommend a three‐phase CT [24, 25]:

1 Arterial phase: to assess for vascular injury and active contrast extravasation

2 Nephrographic phase: to demonstrate parenchymal contusions and lacerations

3 Delayed phase: to identify collecting system injury.

In clinical practice, however, whole‐body trauma imaging is often obtained prior to the involvement of the urologist and delayed phase imaging is not routinely performed. As the optimal timing for delayed phase imaging is 9–10 minutes after contrast injection, another CT can be performed without repeat IV contrast injection if performed within this time window [26]. If there is a PRI on initial imaging and delayed phase imaging was not obtained, a repeat CT with delayed phase imaging is still recommended and can be performed with low risk of contrast‐induced nephropathy [27].

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) organ injury scale is the most commonly‐used tool to grade traumatic solid organ injuries. The AAST staging for renal trauma is shown in Table 2.1. Although it was not originally designed to be a prognostic tool, studies have shown good correlation between higher‐grade renal injuries and need for surgical intervention, such as nephrectomy [28, 29].

Findings on CT that are risk factors for hemorrhage and need for urgent invasive intervention are hematoma with a diameter greater than 3.5 cm, medial renal laceration, and intravascular contrast extravasation. In patients with two or more of these risk factors, the risk of intervention to control bleeding was 66.7% [30].

For higher‐grade renal lacerations (Grade IV–V), penetrating trauma, or patients experiencing complications (fever, ileus, etc.), both the AUA and EAU recommend repeat CT imaging two to four days after the initial trauma, because these are prone to developing complications from their initial injury, such as urinoma or persistent bleeding [24, 25].

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.