Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A comprehensive review of the properties of biocomposites and their applications Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites

Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of BIocomposites

Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Moreover, hybrid biocomposites refer to composites in which two or more different biofibers (natural fibers) are combined in a matrix, or a mixture of natural fibers with synthetic fibers in a matrix [4]. One synthetic fiber commonly used for improving the mechanical response in natural FRP composites is glass or carbon fibers. Several types exist for hybrid composites. These types are dependent on the material constituent mixture [16, 17].

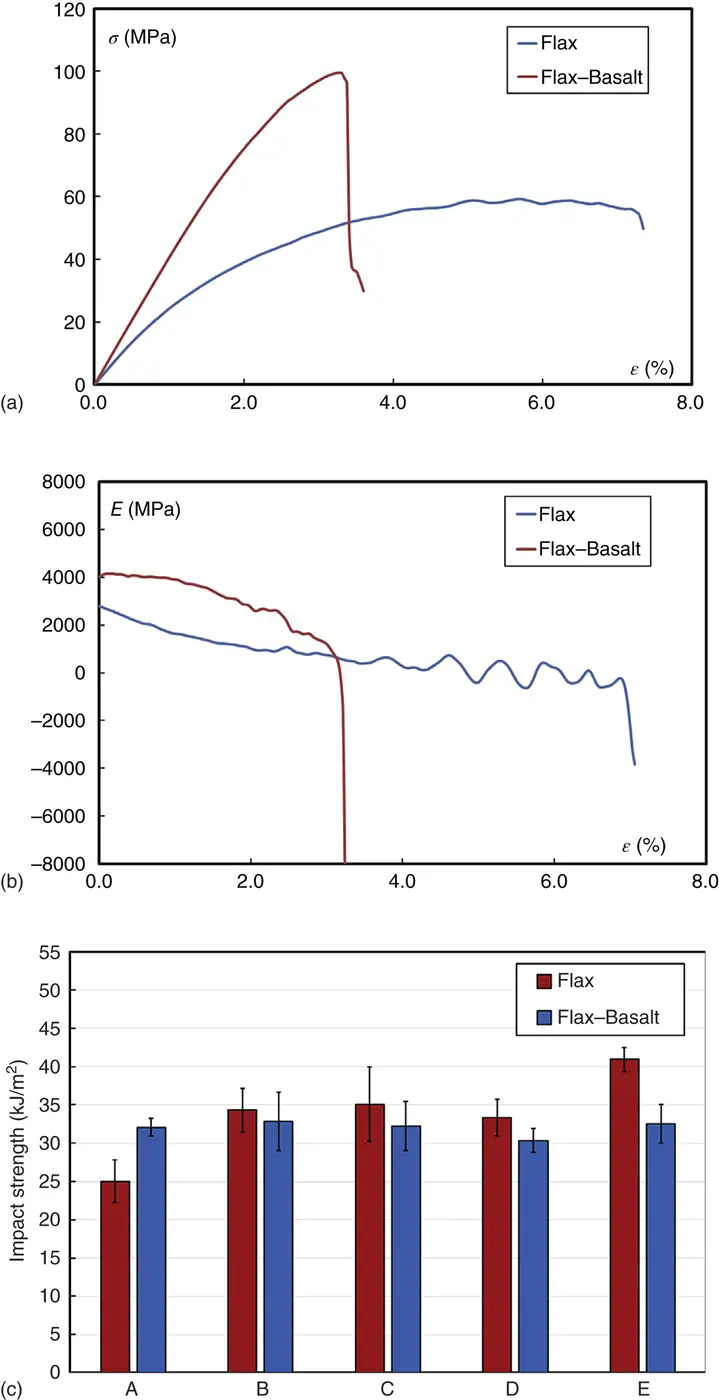

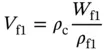

For instance, Figure 1.3shows higher mechanical properties of unaged hybrid flax/basalt FRP composite sample A, when compared with single or non‐hybrid flax FRP composite. However, the impact strength property of the aged hybrid counterpart samples B, C, D, and E changed insignificantly after 15, 30, 45, and 60 aging days of salt‐fog environment conditions ( Figure 1.3c) of the hybrid types. Additional mechanical behaviors of some FRP hybrid biocomposites are presented later in Table 1.5by considering their natural/natural fiber combined reinforcements.

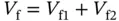

In preparing hybrid FRP composites, the rule of mixture comes to play, while the volume fraction can be obtained using Eqs. (1.1)– (1.6)[8].

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.3)

Figure 1.3 Improved mechanical properties of hybrid flax–basalt fibers FRP composites, depicting (a) stress–strain, (b) modulus–strain curves, and (c) impact strengths of aged and unaged biocomposites.

Source: Fiore et al. [18]. © 2016, Elsevier.

(1.4)

(1.5)

(1.6)

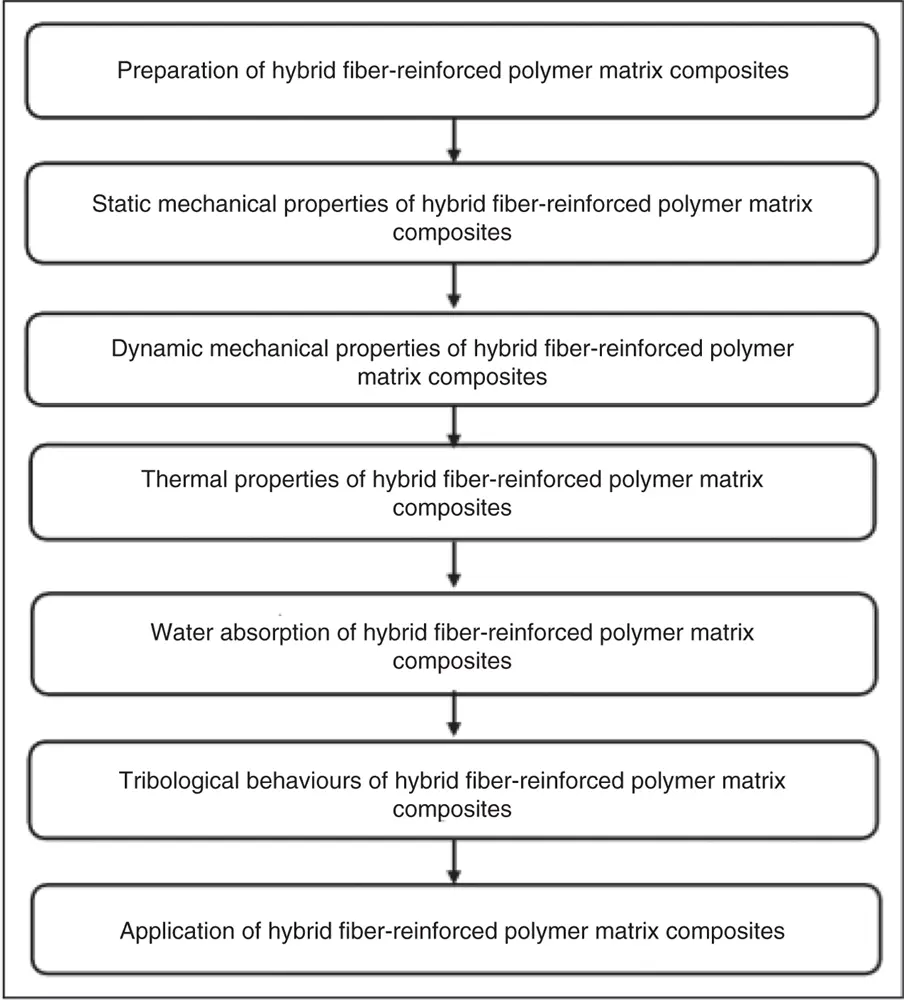

where V fdenotes total reinforcement volume fraction, V c1and V c2represent the first and second reinforcement relative volume fractions, V f1and V f2stand for the first and second fiber volume fractions, ρ cand ρ fdesignate the densities of the composites and fiber, while W findicates the weight of the fiber. The methodology for preparing and characterizing hybrid fiber‐reinforced PMCs as well as its applications is presented in Figure 1.4.

However, the present chapter does not cover all the methodologies shown in Figure 1.4in detail, because the scope of this chapter is not manufacturing processes and techniques of natural FRP composite materials.

1.4 Mechanical Behaviors of Natural Fiber‐Reinforced Polymer‐Based Hybrid Composites

There are many properties of materials that determine where they function or are used in the engineering space. The required characteristics in a proposed design will determine what combinations of materials will be relevant and which of the various mechanical properties are of interest in such instances. Notable among the mechanical properties usually considered in engineering are tensile, compressive, flexural, and impact strengths, among others. These properties are discussed in Section 1.4.1.

Figure 1.4 Flowchart of preparation and characterization of the hybrid FRP composites.

Source: Sathishkumar et al. [8]. © 2014, SAGE Publications.

1.4.1 Hybrid Natural FRP Composites

This section discusses hybrid biocomposites in which their combined fibers are entirely natural (biofibers).

1.4.1.1 Bagasse/Jute FRP Hybrid Composites

Jute is a popular plant‐based fiber (vegetable) with dominant presence in tropical countries across the Asian continent, such as China, Brazil, Nepal, Bangladesh, India, and Thailand. They account for about 95% of jute fiber (JF) production worldwide [4]. Jute is considered as a lignocellulosic bast fiber, having comparative advantages with respect to renewability, biodegradability (which makes it eco‐friendly), high strength as well as high initial modulus over other fibers [11]. Bagasse, also called sugarcane bagasse, is a lingocellulosic by‐product of the sugar industry, mostly utilized as a fuel in boilers and sugar factories. Compared with other residues (by‐products), including wheat straw and rice, bagasse is preferred, because its ash content is lower [19].

A study of mechanical behavior of hybrid FRP composites with short JF and short bagasse fiber (BF) bundles reinforcement was carried out by Saw and Datta [20]. They used epoxidized phenolic novolac (EPN) as resin matrix and investigated various fiber surface treatments and fiber ratios. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) alkali solution was used to treat the JF bundles. The BF bundles were either modified using chlorine dioxide (ClO 2) and furfuryl alcohol (C 5H 6O 2) or left untreated. The modification of the fiber surface was necessary for quinones creation in the lignin areas of the BF bundles. The created quinones then reacted with the furfuryl alcohol, and thereby improved the BF bundles' (modified) ability for better adhesion. Their result revealed greater mechanical responses (flexural, tensile and impact properties) for hybridized BF (modified) and JF bundles (alkali‐treated) in the EPN resin matrix than the BF bundles that were not modified. They obtained an optimum mechanical behavior at a BF/JF ratio of 50 : 50, as depicted in Table 1.5.

1.4.1.2 Bamboo/MFC FRP Hybrid Composites

Asian giants, India and China, are the chief producers of bamboo fiber with more than 80% of global production [21]. This biofiber is highly attractive, due to its renewable nature and low environmental impact. It grows rapidly and has comparative high strength to other biofibers, such as cotton and jute [22].

An unprecedented biocomposite (hybrid) that contained biodegradable poly‐lactic acid (PLA) matrix with microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) and bamboo fiber bundles reinforcements was developed by Okubo et al. [23]. Various nomenclatures have been used for describing MFC in the literature, such as microfibril, microfibrillar cellulose, microfibril aggregates, nanofibril, nanofibrillar cellulose, nanofiber, and fibril aggregates [24]. They conducted an investigation on how MFC dispersion influenced the responses of composites reinforced with bamboo fibers by dispersing MFC in a polymer matrix of PLA by a three‐roll mill calendering process. This calendering process helps to compress or smoothen a material. They used the PLA (bio‐based and biodegradable) polymer matrix for interfacial bonding enhancement with the MFC. The diameter of bamboo fiber bundles was about 200 μm, while that of MFC was just a few microns, which was much smaller. Using gap settings in decreasing order of 70, 50, 35, 25, 15, 10, and 5 μm, they processed the mixture of the MFC and PLA in the three‐roll mill. About 200% increase in the fracture energy was realized when they added 1 wt.% of MFC to the PLA matrix and milled the MFC/PLA composite at the smallest gap setting of 5 μm, which was quite significant. This hybrid composite combination of bamboo fiber and the PLA matrix with 1 wt.% MFC reinforcement was observed to prevent an abrupt crack channel through the bamboo fiber effectively, and thus produced a significant improvement in fracture strength. The results of other mechanical behaviors are presented in Table 1.5.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mechanical and Dynamic Properties of Biocomposites» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.