In Fp, Fe content may play a role in controlling deformation mechanisms. Subtle change in textures observed in room temperature DAC experiments may be linked to reduced activity of {110}〈1  0〉 (Tommaseo et al., 2006). In low pressure, high‐temperature shear experiments (300 MPa and up to 1473K), changes in deformation mechanisms appear to be most pronounced in samples with Fe contents in excess of 50% (Long et al., 2006). During high‐temperature deformation of Fp to high shear strains, {111}〈1

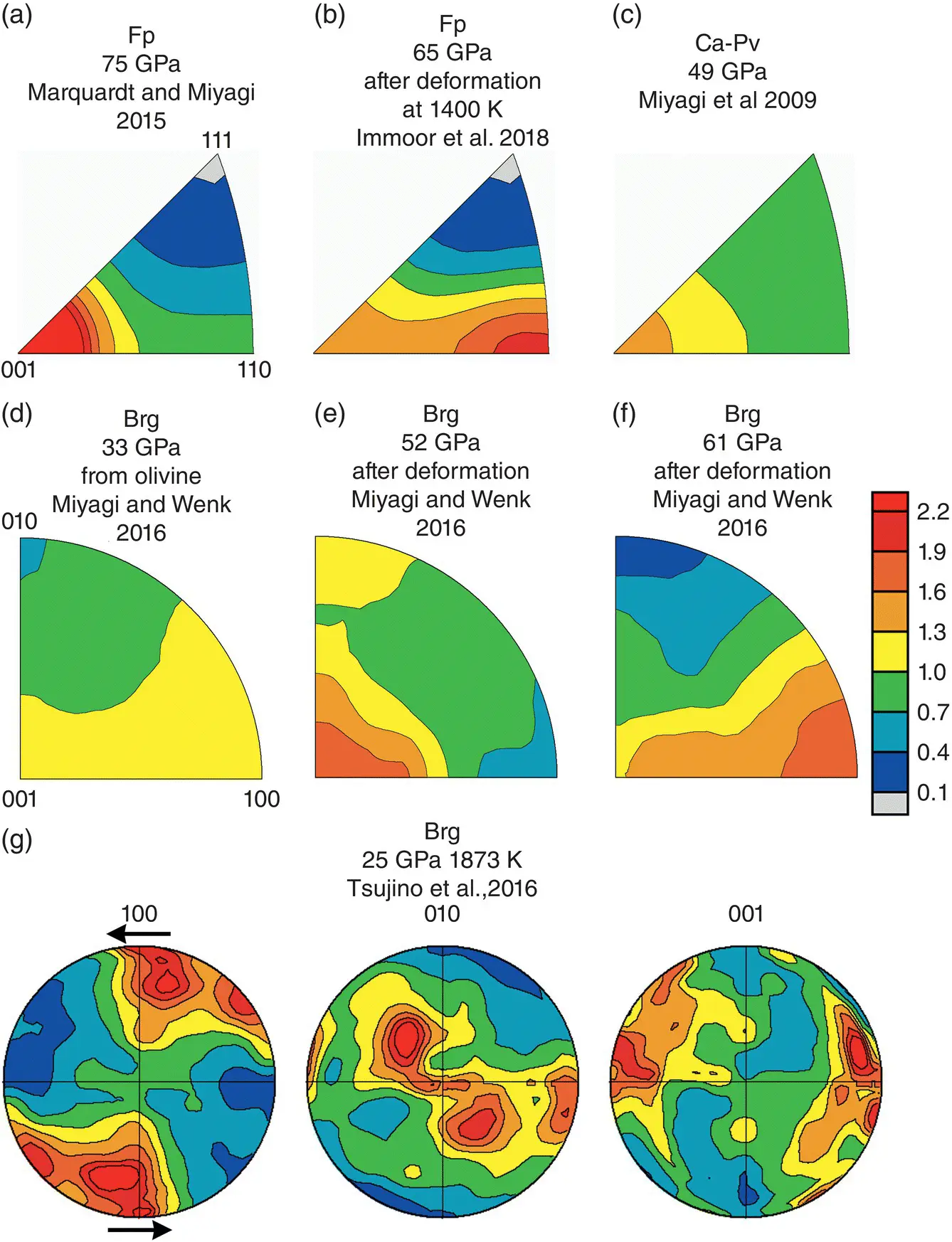

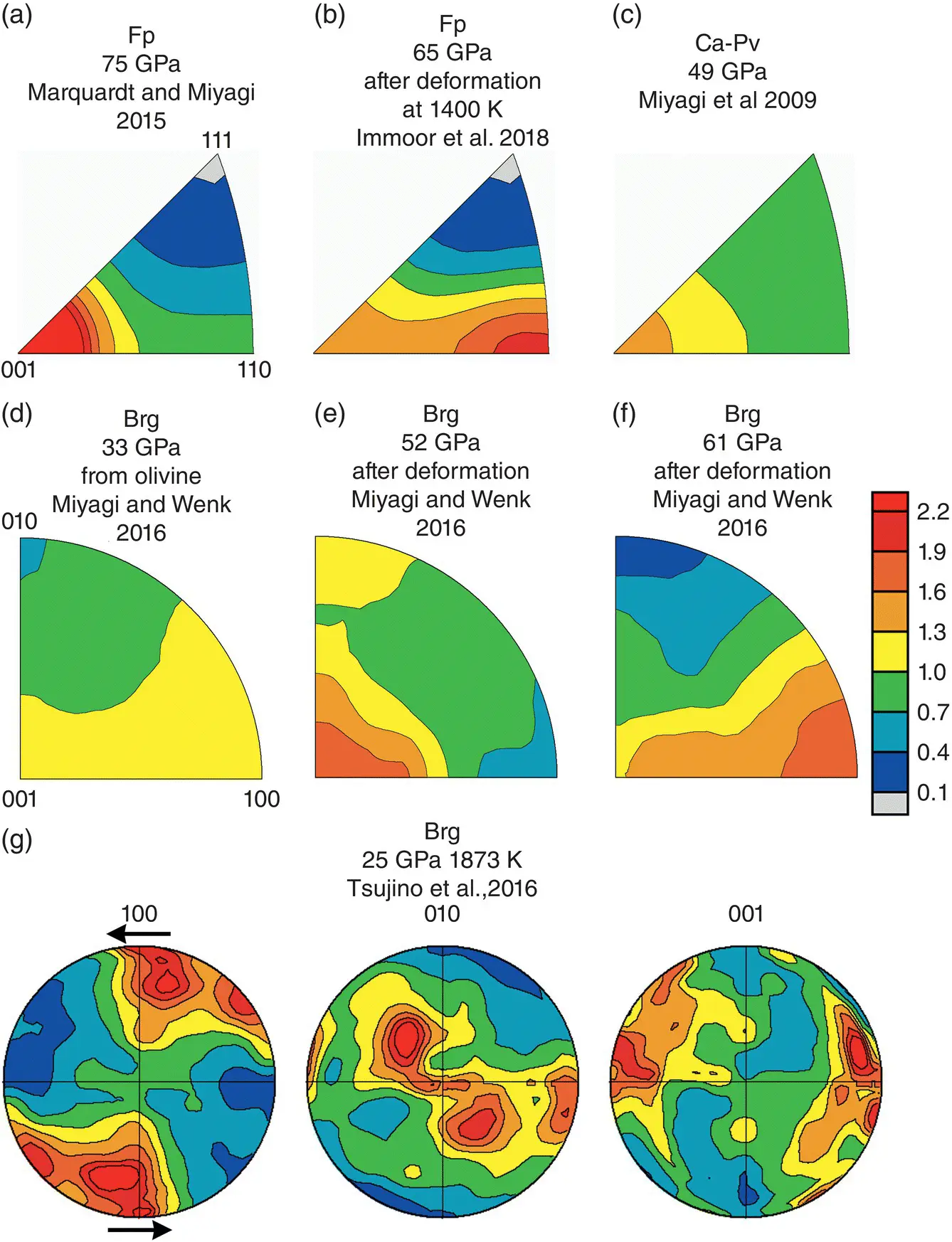

0〉 (Tommaseo et al., 2006). In low pressure, high‐temperature shear experiments (300 MPa and up to 1473K), changes in deformation mechanisms appear to be most pronounced in samples with Fe contents in excess of 50% (Long et al., 2006). During high‐temperature deformation of Fp to high shear strains, {111}〈1  0〉 slip may also be activated (Heidelbach et al., 2003; Long et al., 2006; Yamazaki & Karato, 2002). Recent resistive heated DAC experiments on Fp show a transition to a {110} maximum in IPFs of the compression direction ( Figure 2.4b), and this is attributed to increased activity of {100}〈011〉 slip with temperature at mantle pressures (Table 1). At ~1400K and pressures of 30–60 GPa both {110}〈1

0〉 slip may also be activated (Heidelbach et al., 2003; Long et al., 2006; Yamazaki & Karato, 2002). Recent resistive heated DAC experiments on Fp show a transition to a {110} maximum in IPFs of the compression direction ( Figure 2.4b), and this is attributed to increased activity of {100}〈011〉 slip with temperature at mantle pressures (Table 1). At ~1400K and pressures of 30–60 GPa both {110}〈1  0〉 and {100}〈011〉 slip systems are ~equally active (Immoor et al., 2018). Based on current experimental data, it appears that {110}〈1

0〉 and {100}〈011〉 slip systems are ~equally active (Immoor et al., 2018). Based on current experimental data, it appears that {110}〈1  0〉 is typically dominant in Fp at lower pressure and temperature and at high pressure and temperature {100}〈011〉 becomes increasingly dominant ( Table 2.1).

0〉 is typically dominant in Fp at lower pressure and temperature and at high pressure and temperature {100}〈011〉 becomes increasingly dominant ( Table 2.1).

Figure 2.4 Summary of textures observed in ferropericlase (a) and (b), CaSiO 3perovskite (c), and in bridgmanite (d–g). Textures are shown as equal area, upper hemisphere, projection inverse pole figures of the compression direction for (a–f). Due to the lower symmetry deformation geometry (shear) the texture data of Tsujino et al. (2016) are represented as pole figures of (100) (010), and (001). Black arrows indicate the sense of shear. The textures plotted in g) are those from the extended data figure 7 of Tsujino et al. (2016) which were obtained using the Materials Analysis Using Diffraction program (Lutterotti et al., 1997). Scale bar is in multiples of random distribution.

There is only one room temperature deformation experiment measuring texture development in Ca‐Pv (Miyagi et al., 2009). This experiment measured texture development at ~25–50 GPa and found a {100} compression texture ( Figure 2.4c) consistent with deformation on the {110}〈1  0〉 slip system ( Table 2.1; pseudo cubic reference). This is consistent with computational work (Ferré et al., 2009). One should note that Ca‐Pv deviates from the cubic symmetry but the structure is poorly constrained due to the small deviations from cubic symmetry. Several potential lower symmetry structures have been proposed (Shim et al., 2002).

0〉 slip system ( Table 2.1; pseudo cubic reference). This is consistent with computational work (Ferré et al., 2009). One should note that Ca‐Pv deviates from the cubic symmetry but the structure is poorly constrained due to the small deviations from cubic symmetry. Several potential lower symmetry structures have been proposed (Shim et al., 2002).

Deformation of Bridgmanite.

A few deformation studies exist on Brg, using the DAC (Meade et al., 1995; Meade & Jeanloz, 1990; Merkel et al., 2003; Miyagi & Wenk, 2016; Wenk et al., 2004; Wenk, Lonardelli, et al., 2006), a modified large‐volume press assembly (Chen et al., 2002; Cordier et al., 2004; Tsujino et al., 2016), and the RDA (Girard et al., 2016). Early DAC deformation studies of Brg found no evidence for texture development in decompressed samples (Meade et al., 1995) or in in‐situ measurements of samples deformed outside the Brg stability field (Merkel et al., 2003). In contrast, Wenk et al. (2004) and Wenk, Lonardelli, et al. (2006) reported significant texture development in Brg and Brg + Fp aggregates synthesized in‐situ in the DAC from different starting materials. Different textures were observed, depending on starting material, and it was suggested that textures could be explained by slip on (010)[100], (100)[010], and (001)(110). Twinning on (110) was also suggested as a mechanism for texture development (Wenk et al., 2004). However, subsequent measurements by Miyagi & Wenk (2016) showed that the wide range of textures observed in Wenk et al. (2004) were likely due to the phase transformation from varied starting materials. Synthesis of bridgmanite from enstatite results in a strong (001) transformation texture while synthesis from olivine or ringwoodite results in a weak (100) transformation texture (e.g., Figure 2.4d; Miyagi & Wenk, 2016).

Twinning has been documented in Brg and is associated with the phase transformation to Brg but also has been observed in stress relaxation experiments. TEM studies of recovered samples from high‐pressure experiments documented reflection twins on (110) and (112) (Martinez et al., 1997; Y. Wang et al., 1990, 1992). In‐situ stress relaxation measurements at 20 GPa and 1073 K using the LVP and also found evidence for activity of (110) twinning (Chen et al., 2002).

Experimental evidence for slip systems in Brg generally shows either deformation on (001) planes or (100) planes. Several studies have documented texture, line broadening, or TEM observations consistent with slip on (001) planes. Cordier et al. (2004) suggested (001)[100] and (001)[010] dislocations based on x‐ray line broadening analysis of samples recovered from a large‐volume press deformation experiment at 25 GPa and 1700 K. A TEM study by Miyajima et al. (2009) documented 〈110〉 Burgers vectors, indicating that the likely slip plane is (001). Room‐temperature DAC experiments observed a (001) maximum at pressures < 55 GPa and room temperature ( Figure 2.4e), consistent with dominant (001) slip, with some combination of slip in [100], [010], and 〈110〉 directions (Miyagi & Wenk, 2016). However, after laser annealing and compression above 55 GPa, Miyagi & Wenk (2016) observed a (100) texture maximum ( Figure 2.4f) consistent with slip on (100). Interestingly, numerical modeling using first principles and the Peierls‐Nabarro model suggests that at pressures < 30GPa, slip on (001)〈110〉 is dominant, but at higher pressures (100)[010] slip is more active in Brg (Mainprice et al., 2008). Recent shear deformation experiments to 80% strain at 25 GPa and 1873 K in the D‐DIA with a Kawai type assembly showed textures consistent with slip on (100)[001] ( Figure 2.2g; Tsujino et al., 2016).

Generally, numerical models to evaluated slip system strengths find that (010)[100] and (100)[010] should be the easiest slip systems (Ferré et al., 2007; Gouriet et al., 2014; Hirel et al., 2014). So far, experiments have not documented evidence for (010) slip. One should note, however, that due to geometric constraints and the number of symmetric variants, the easiest slip systems is not always most active during deformation (Mainprice et al., 2008). Based on experiments, it appears that at lower pressures and room temperature, slip on (001) dominates, but at higher pressure and at higher temperature (100), slip appears to be active ( Table 2.1). However, systematic studies of slip system changes in Brg as a function of temperature, pressure, strain rate, and composition have not been performed and remain technically challenging. Furthermore, numerical simulations indicate that in the lower mantle, pure‐climb creep (Nabarro, 1967) may be the dominant deformation mechanism (Boioli et al., 2017; Cordier & Goryaeva, 2018; Reali et al., 2019), but due to experimental limitations, this deformation regime has yet to be explored in bridgmanite.

Читать дальше

0〉 (Tommaseo et al., 2006). In low pressure, high‐temperature shear experiments (300 MPa and up to 1473K), changes in deformation mechanisms appear to be most pronounced in samples with Fe contents in excess of 50% (Long et al., 2006). During high‐temperature deformation of Fp to high shear strains, {111}〈1

0〉 (Tommaseo et al., 2006). In low pressure, high‐temperature shear experiments (300 MPa and up to 1473K), changes in deformation mechanisms appear to be most pronounced in samples with Fe contents in excess of 50% (Long et al., 2006). During high‐temperature deformation of Fp to high shear strains, {111}〈1  0〉 slip may also be activated (Heidelbach et al., 2003; Long et al., 2006; Yamazaki & Karato, 2002). Recent resistive heated DAC experiments on Fp show a transition to a {110} maximum in IPFs of the compression direction ( Figure 2.4b), and this is attributed to increased activity of {100}〈011〉 slip with temperature at mantle pressures (Table 1). At ~1400K and pressures of 30–60 GPa both {110}〈1

0〉 slip may also be activated (Heidelbach et al., 2003; Long et al., 2006; Yamazaki & Karato, 2002). Recent resistive heated DAC experiments on Fp show a transition to a {110} maximum in IPFs of the compression direction ( Figure 2.4b), and this is attributed to increased activity of {100}〈011〉 slip with temperature at mantle pressures (Table 1). At ~1400K and pressures of 30–60 GPa both {110}〈1  0〉 and {100}〈011〉 slip systems are ~equally active (Immoor et al., 2018). Based on current experimental data, it appears that {110}〈1

0〉 and {100}〈011〉 slip systems are ~equally active (Immoor et al., 2018). Based on current experimental data, it appears that {110}〈1  0〉 is typically dominant in Fp at lower pressure and temperature and at high pressure and temperature {100}〈011〉 becomes increasingly dominant ( Table 2.1).

0〉 is typically dominant in Fp at lower pressure and temperature and at high pressure and temperature {100}〈011〉 becomes increasingly dominant ( Table 2.1).

0〉 slip system ( Table 2.1; pseudo cubic reference). This is consistent with computational work (Ferré et al., 2009). One should note that Ca‐Pv deviates from the cubic symmetry but the structure is poorly constrained due to the small deviations from cubic symmetry. Several potential lower symmetry structures have been proposed (Shim et al., 2002).

0〉 slip system ( Table 2.1; pseudo cubic reference). This is consistent with computational work (Ferré et al., 2009). One should note that Ca‐Pv deviates from the cubic symmetry but the structure is poorly constrained due to the small deviations from cubic symmetry. Several potential lower symmetry structures have been proposed (Shim et al., 2002).