16.See the account of Pythagoras and his philosophy in Lewes' History of Philosophy, pp. 18-38 (1871).

17.See Section i, 24, 32, 35; Section ii, 28, 29, 30, 35.

18.As a specimen of what the ablest Sung scholars teach, I may give the remarks (from the I Collected Comments') of K û K ăn (of the same century as K û Hsî, rather earlier) on the 4th paragraph of Appendix V:--In the Yî there is the Great Extreme. When we speak of the yin and yang, we mean the air (or ether) collected in the Great Void. When we speak of the Hard and Soft, we mean that ether collected, and formed into substance. Benevolence and righteousness have their origin in the great void, are seen in the ether substantiated, and move under the influence of conscious intelligence. Looking at the one origin of all things we speak of their nature; looking at the endowments given to them, we speak of the ordinations appointed (for them). Looking at them as (divided into) heaven, earth, and men, we speak of their principle. The three are one and the same. The sages wishing that (their figures) should be in conformity with the principles underlying the natures (of men and things) and the ordinances appointed (for them), called them (now) yin and yang, (now) the hard and the soft, (now) benevolence and righteousness, in order thereby to exhibit the ways of heaven, earth, and men; it is a view of them as related together. The trigrams of the Yî contain the three Powers; and when they are doubled into hexagrams, there the three Powers unite and are one. But there are the changes and movements of their (several) ways, and therefore there are separate places for the yin and yang, and reciprocal uses of the hard and the soft.'

19.Dissertation on the Theology of the Chinese, pp. 111, 112.

20.Theology of the Chinese, p. 122.

21.Translation of the Yî King, p. 312.

22.Section i, 23, 32, 51, 58, 62, 64, 67, 68, 69, 73, 76, 81; Section ii, 11, 15, 33, 34, 41, 45.

23. K ung-yung xxxi, 4.

24.Section i, 34. This is the only paragraph where kwei-shăn occurs.

25.Section ii, 5.

26.This view seems to be in accordance with that of Wû Kh ăng (of the Yüan dynasty), as given in the 'Collected Comments' of the Khang-hsî edition. The editors express their approval of it in preference to the interpretation of K û Hsî, who understood the whole to refer to the formation of the lineal figures, the 'application' being 'the manipulation of the stalks to find the proper line.'

27.But the Chinese term Shăng  , often rendered 'produced,' must not be pressed, so as to determine the method of production, or the way in which one thing comes from another.

, often rendered 'produced,' must not be pressed, so as to determine the method of production, or the way in which one thing comes from another.

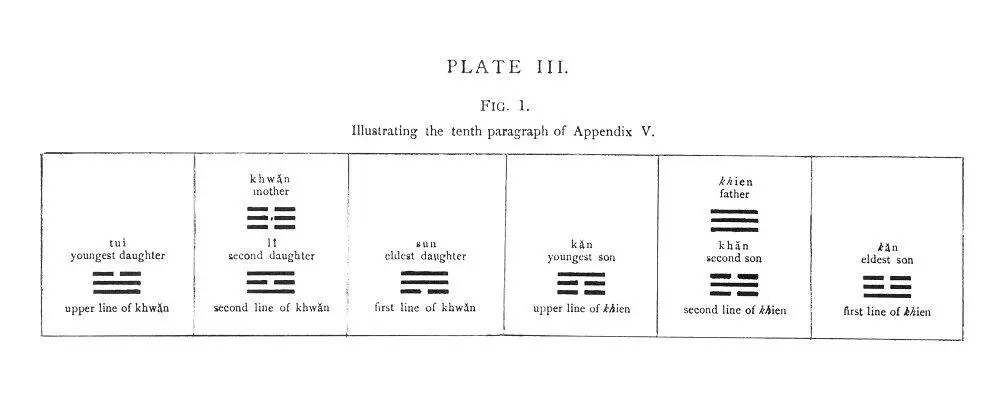

28.The significance of the mythological paragraph is altogether lost in Canon McClatchie's version:--' Kh ien is Heaven, and hence he is called Father; Khwăn is Earth, and hence she is called Mother; K ăn is the first male, and hence he is called the eldest son,' &c. &c.

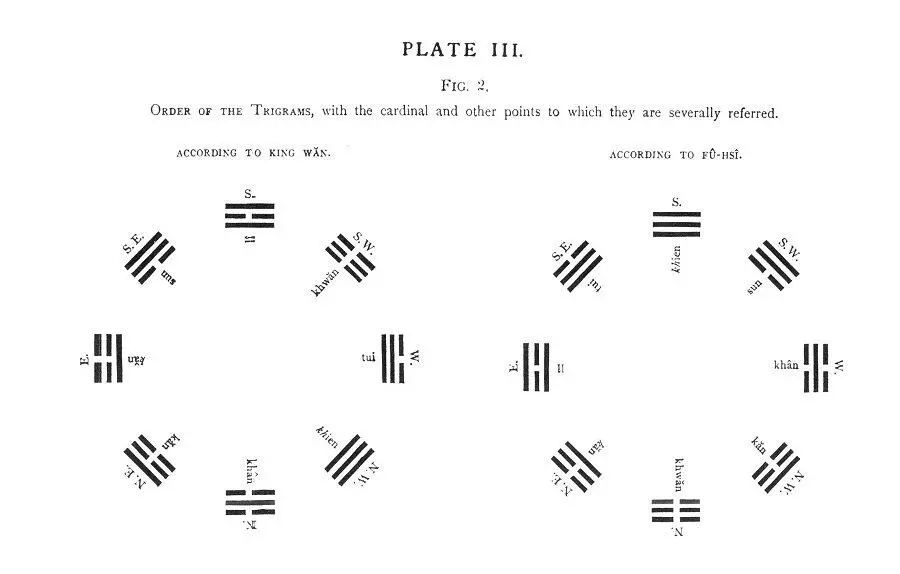

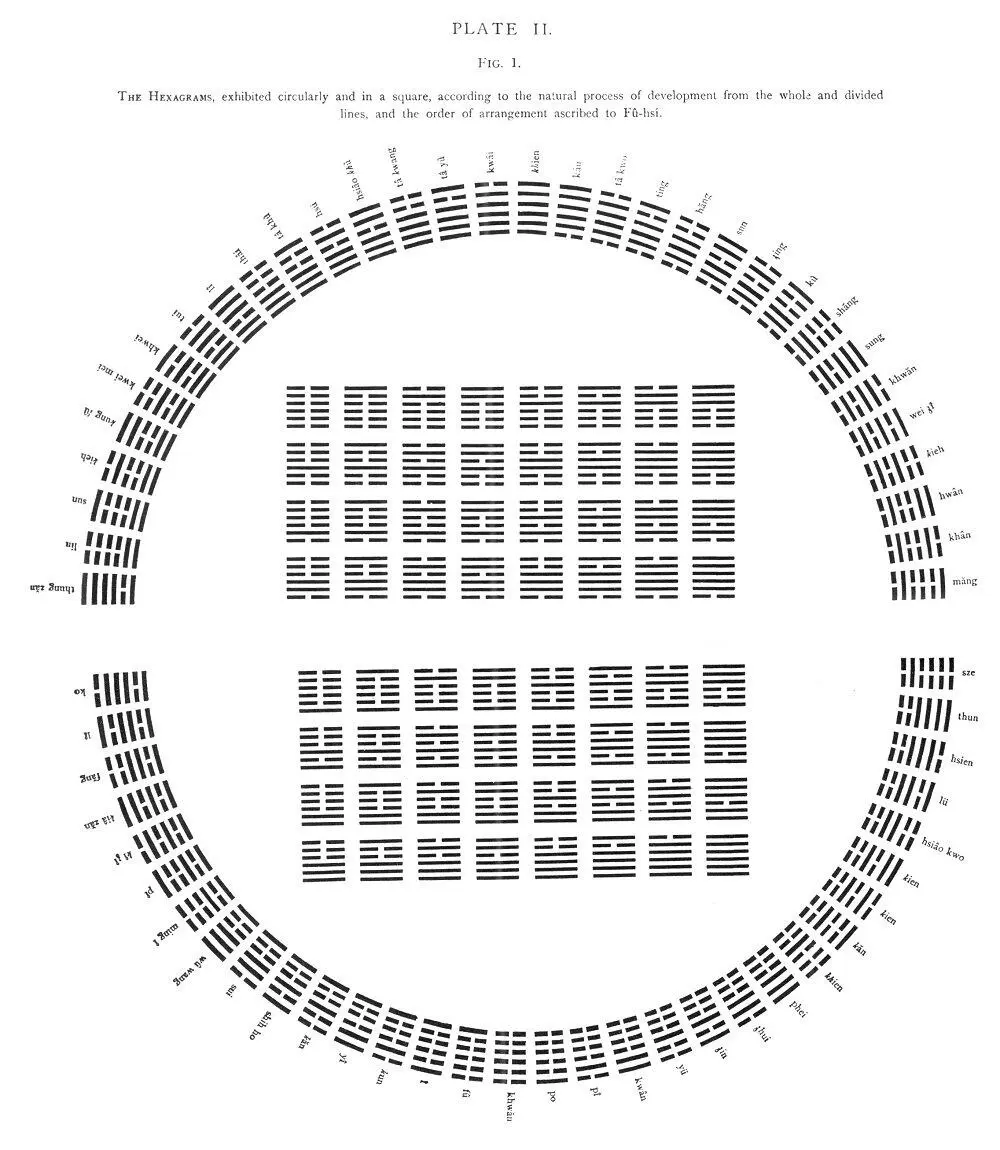

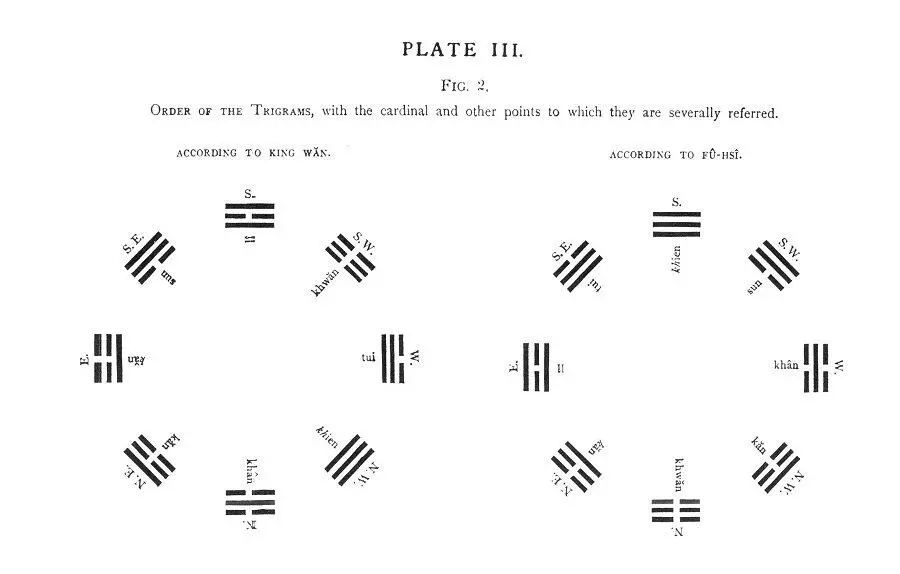

29.The reader will understand the difference in the two arrangements better by a reference to the circular representations of them on Plate III.

30.E. g. 1, 23, 24:--'Observant etiam philosophi (lib. 15 Sinicae philosophiae Sing-11) principem. Wăn-wang antiquum octo symbolorum, unde aliae figurae omnes pendent, ordinem invertisse; quo ipsa imperii suis temporibus subversio graphice exprimi poterat, mutatis e naturali loco, quem genesis dederat, iis quatuor figuris, quae rerum naturalium pugnis ac dissociationibus, quas posterior labentis anni pars afferre solet, velut in antecessum, repraesentandis idoneae videbantur; v. g. si symbolum  Lî, ignis, supponatur loco symboli

Lî, ignis, supponatur loco symboli  Khân, aquae, utriusque elementi inordinatio principi visa est non minus apta ad significandas ruinas et clades reipublicae male ordinatae, quam naturales ab hieme aut imminente aut saeviente rerum generatarum corruptiones.' See also pp. 67, 68.

Khân, aquae, utriusque elementi inordinatio principi visa est non minus apta ad significandas ruinas et clades reipublicae male ordinatae, quam naturales ab hieme aut imminente aut saeviente rerum generatarum corruptiones.' See also pp. 67, 68.

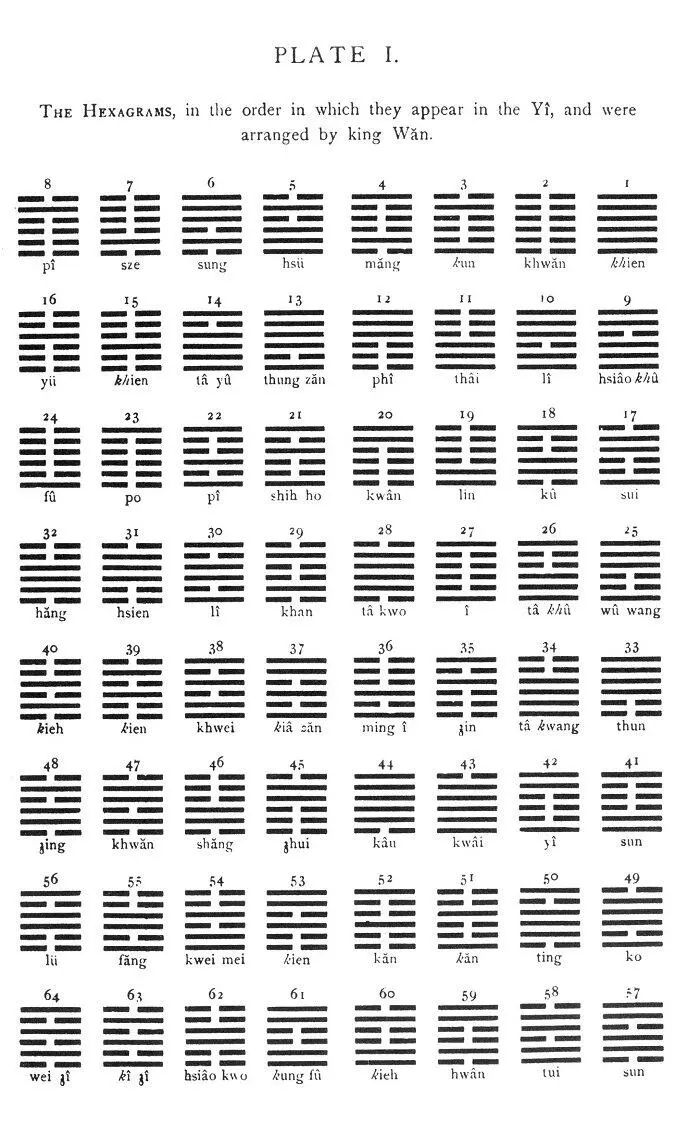

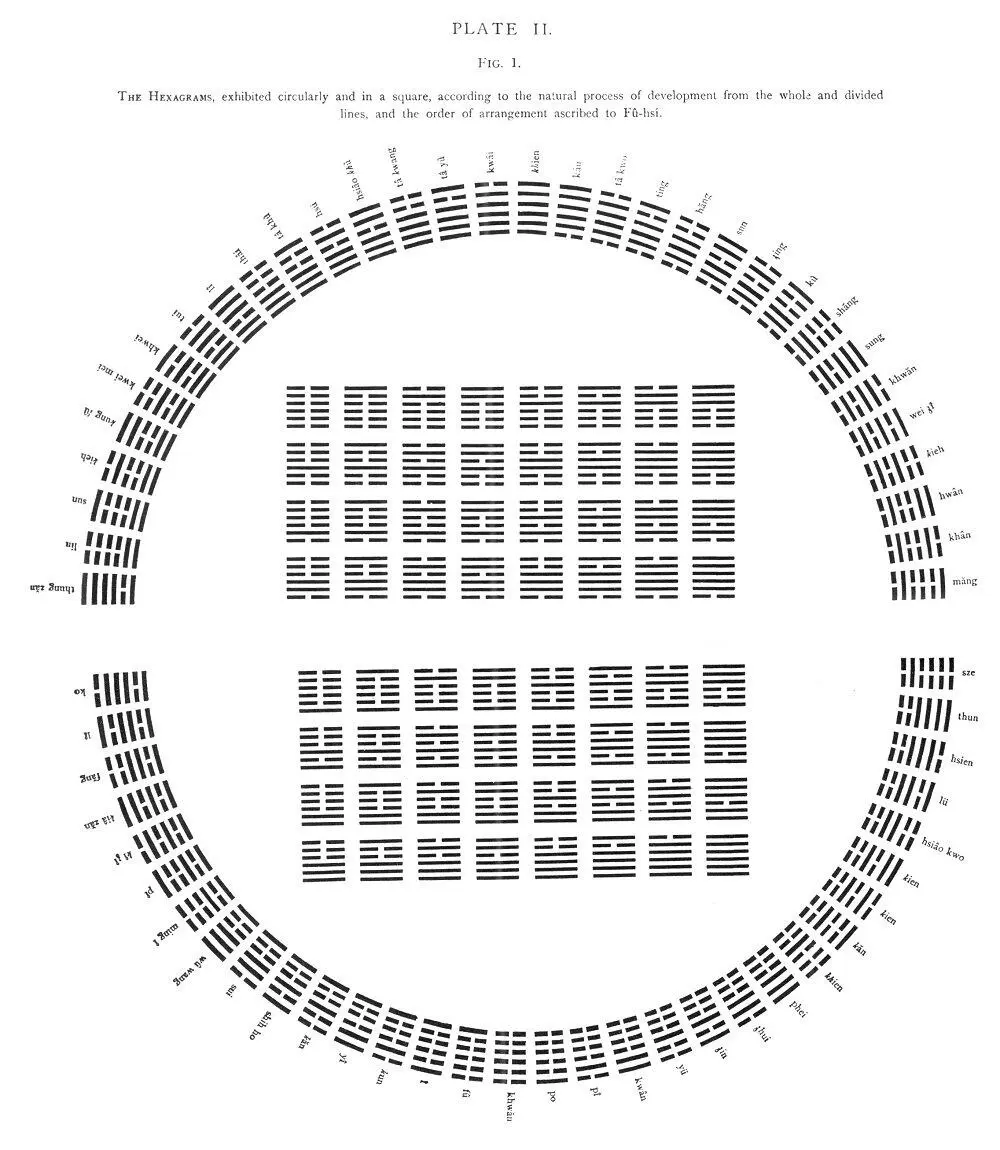

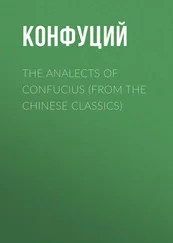

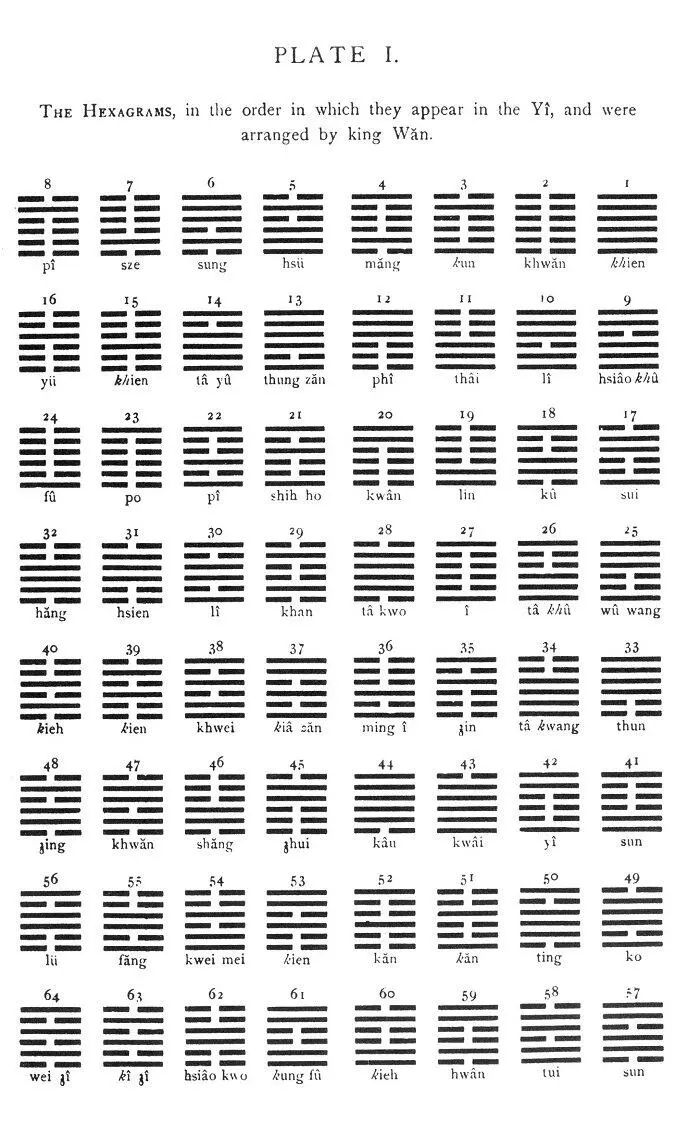

PLATES I, II, III, EXHIBITING THE HEXAGRAMS AND TRIGRAMS

Table of Contents

The HEXAGRAMS, in the order in which they appear in the Yî, and were arranged by Kin Wăn.

Fig. 1.

The HEXAGRAMS, exhibited circularly and in a square, according to the natural process of development from the whole and divided lines, and the order ascribed to Fû-hsî.

Fig 2.

The Trigrams distinguished as Yin and Yang.

Fig 1.

Illustrating the tenth paragraph of Appendix V.

Fig 2.

ORDER OF THE TRIGRAMS, with the cardinal and other points to which they are severally referred.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Explanation of the entire figure by king Wăn

Kh ien (represents) what is great and originating, penetrating, advantageous, correct and firm.

Explanation of the separate lines by the duke of K âu.

1. In the first (or lowest) line, undivided, (we see its subject as) the dragon lying hid (in the deep). It is not the time for active doing.

2. In the second line, undivided, (we see its subject as) the dragon appearing in the field. It will be advantageous to meet with the great man.

3. In the third line, undivided, (we see its subject as) the superior man active and vigilant all the day, and in the evening still careful and apprehensive. (The position is) dangerous, but there will be no mistake.

4. In the fourth line, undivided, (we see its subject as the dragon looking) as if he were leaping up, but still in the deep. There will be no mistake.

5. In the fifth line, undivided, (we see its subject as) the dragon on the wing in the sky. It will be advantageous to meet with the great man.

6. In the sixth (or topmost) line, undivided, (we see its subject as) the dragon exceeding the proper limits. There will be occasion for repentance.

7. (The lines of this hexagram are all strong and undivided, as appears from) the use of the number line. If the host of dragons (thus) appearing were to divest themselves of their heads, there would be good fortune.

Читать дальше

, often rendered 'produced,' must not be pressed, so as to determine the method of production, or the way in which one thing comes from another.

, often rendered 'produced,' must not be pressed, so as to determine the method of production, or the way in which one thing comes from another. Lî, ignis, supponatur loco symboli

Lî, ignis, supponatur loco symboli  Khân, aquae, utriusque elementi inordinatio principi visa est non minus apta ad significandas ruinas et clades reipublicae male ordinatae, quam naturales ab hieme aut imminente aut saeviente rerum generatarum corruptiones.' See also pp. 67, 68.

Khân, aquae, utriusque elementi inordinatio principi visa est non minus apta ad significandas ruinas et clades reipublicae male ordinatae, quam naturales ab hieme aut imminente aut saeviente rerum generatarum corruptiones.' See also pp. 67, 68.