It will be appreciated, too, that the socket of the deciduous canine is much narrower than the broad permanent canine crown. Moreover, normal healing of most of the more occlusal portion of the socket will have occurred and bone regenerated, much before the canine even reaches its more occlusal lower levels. One must assume, therefore, that the tooth will meet with resistance not only from the mature peripheral alveolar socket bone in the apical areas of the socket wall, but also from the more recently infiltrated young alveolar bone, which must be resorbed to make way for the eruption of the tooth. By retaining the buccal bridge of bone during surgery (given the conservative attitude to bone removal in general), the tooth will come down through an uncompromised bony matrix. The final outcome will show the aligned tooth to have excellent bony support, in terms of both its width and the level of the alveolar crest.

In considering the location and orientation of most impacted maxillary canines, each method of surgical exposure has its advantages and its drawbacks. These are apparent in relation to efficacy of treatment and post‐surgical recovery, as well as regarding the overall treatment outcome in relation to aesthetics, periodontal prognosis and stability of the final result. An ‘aggressive’ canine that is located within the resorption crater that it has carved into the root of the adjacent incisor is a case in point. It is almost certain that an open surgical exposure would cause the loss of vitality of that incisor. However, a carefully performed closed exposure can usually be expected to enable the incisor to maintain its vitality. Similarly, the open surgical exposure method is not advised for severely ectopic canines, canines that are found in the more difficult sites, such as high above the apices of the other teeth, or those in locations where open surgery would involve leaving denuded root surfaces of adjacent teeth exposed to the oral environment. The deeper and more distant the impacted tooth is located within the jaw bone, the more radical is the bone resection that is required in order to ensure that the exposed crown of the tooth will not heal over in the weeks that follow. Open exposures in these more difficult situations are also more likely to adversely affect the patient’s quality of life in the immediate post‐surgical weeks, in terms of pain, recurrent bleeding, taste, halitosis and general function [20].

Even though the orthodontist may or may not be present during a closed surgical technique procedure, it is nevertheless imperative that an attachment be bonded at that time. It is obviously propitious to apply the eruptive force to the impacted tooth immediately, taking full advantage of the prevailing anaesthesia. The absence of the orthodontist will place the onus to do this, squarely but unfairly, on the shoulders of the surgeon.

In contrast, when open surgery is performed, the presence of the orthodontist is unnecessary, since the aim of the surgery is merely to prepare the stage for the future placement of an attachment by the orthodontist in his or her office. Accordingly, the surgeon must complete the exposure in such a manner as to be sure that the tissues will not heal over and make the tooth inaccessible in the few post‐surgical weeks, until an attachment is bonded in the orthodontist’s office and traction begins. Since orthodontic procedures in general do not require local anaesthesia, the orthodontist is unlikely to offer it to the patient at the next orthodontic appointment, even though there is a general sensitivity of the area, even to gentle manipulation. Inevitably, because the anaesthetic will not be given and because the orthodontist is not present at the surgical procedure and because the surgeon will not apply traction at the time, there is a loss of momentum in the progress of treatment. The first visit to the orthodontist will not be for quite a long time and it is inevitable that there will be an additional delay in the commencement of traction. It is therefore beneficial, even for the open procedures, that an attachment be placed at the time of surgery and to apply traction, in order to maintain the treatment momentum.

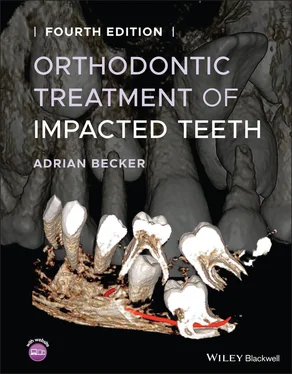

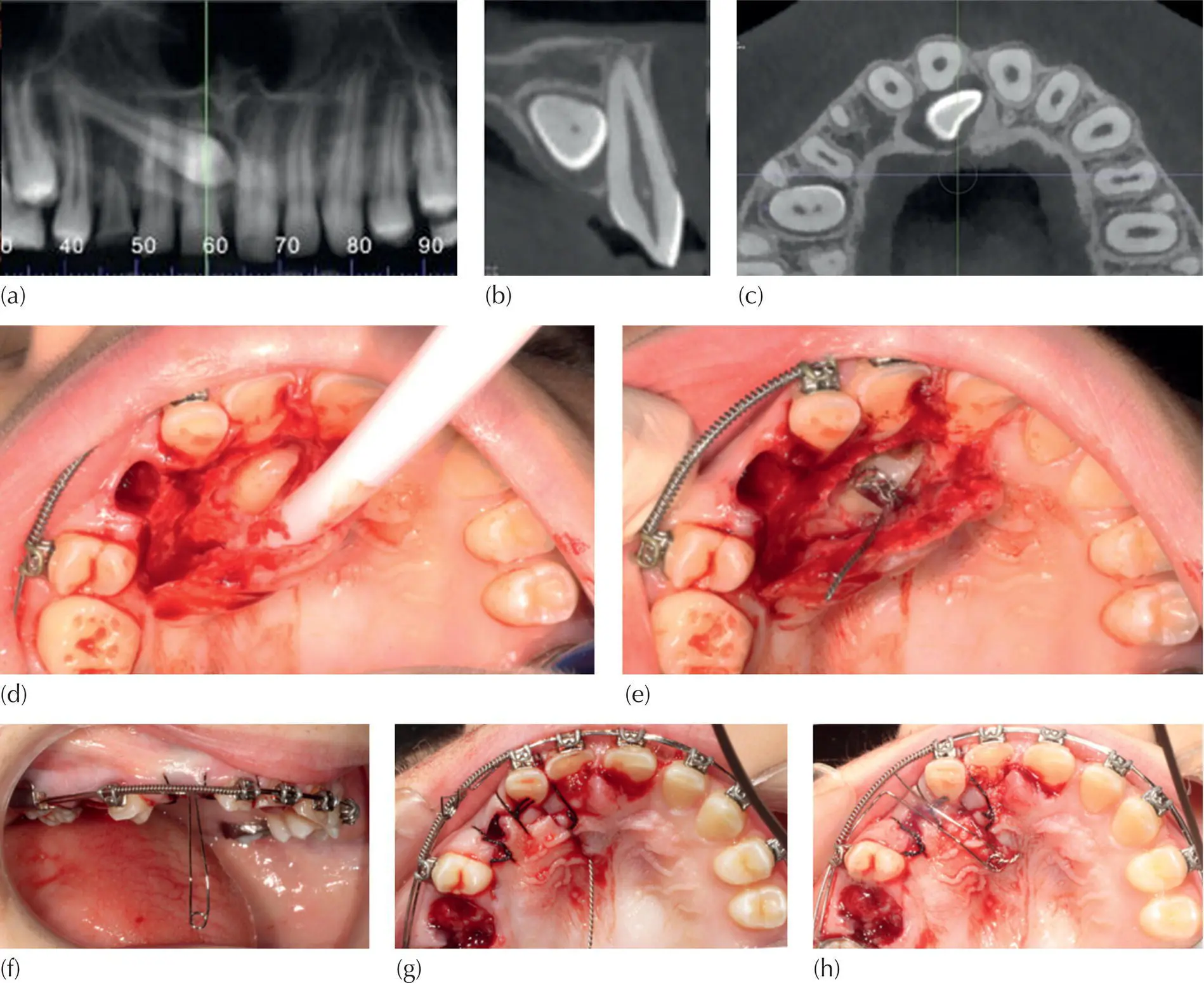

CBCT imaging of the impacted canine, in the case shown above, pinpointed the exact location of the canine ( Figure 5.6a–c) and this enabled the direction of traction to be determined. The other serial slices and 3D reconstructions performed on the material have illustrated the level of technical difficulty of resolution of the impaction and subsequent alignment of the tooth. They have, however, also shown an apparently healthy PDL and an absence of signs of resorption and other pathology, both of the canine itself and of the roots of the adjacent teeth, which would determine whether or not the tooth would respond to orthodontic forces.

Fig. 5.6 Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging slices of a palatally impacted canine that has crossed the midline, as seen on (a) a panoramic curved slice (b) a cross‐sectional slice and (c) an axial slice. The long axis of the canine is oriented approximately 10° to the horizontal. (d) A wide flap has been reflected, the deciduous canine extracted and the canine exposed. (e) An eyelet has been bonded to the most accessible location on the crown of the canine, with the twisted wire connector hanging loosely. (f) The surgical flap was re‐sutured back to its former place, the loop of the auxiliary archwire in its passive (vertical) mode, after ligation over the main archwire. (g) The twisted ligature connector from the eyelet has been drawn through a small piercing in the flap, located immediately opposite the eyelet above it. (h) The vertical loop of the auxiliary archwire is turned inwards and latched by the shortened connector, in contact with the palatal mucosa.

The crown of the impacted canine was exposed using a wide flap, but with minimal removal of bone. The deciduous canine was extracted. The unexposed crown lay between the root apices of the central incisors. Due to the obstruction caused by the roots of both the central and lateral incisors of the right side, it had traversed the anatomical midline, from where it had no available direct route to its appropriate place in the dental arch.

An attachment was bonded by the orthodontist, while haemostasis was maintained by the surgeon. The location for the bonding, chosen by the orthodontist, was the anatomically distal aspect of the rotated crown of the canine. This was also the most superficial and accessible site. A twisted steel ligature pigtail had been tied into the eyelet prior to its placement and was intended as the means of transferring extrusive force to the tooth.

The flap was pierced at the point where the flap covered the eyelet, to accommodate the ligature pigtail in its desired position, close to the midline. The pigtail was pushed through the pierced hole, before the flap was fully replaced and re‐sutured.

An auxiliary labial archwire, with a vertical loop, was ligated at this point in piggyback fashion over the heavier base arch and its loop turned inwards and upwards. It was securely latched, in light horizontal contact, to the palatal mucosa, by the shortened and bent‐over twisted ligature. Active vertical extrusive force would now erupt the tooth vertically downward, towards the tongue. From that point, a direct approach to the archwire could then be made, without interference by the incisor root.

In a situation where a palatal canine is located very high up in the maxilla, at the level of and close to the midline and to the incisor apices, an open exposure is contraindicated. There is every likelihood that the exposure will close over in the immediate post‐surgical period, together with the possibility of loss of vitality of one or more of the incisors. The canine seen in Figure 5.6was located across the midline and between the central incisor apices. The tooth was subsequently drawn posteriorly and vertically downwards, exiting in the mid‐palate and thereby avoiding damaging the incisor apices and permitting lateral movement to its place in the arch. The initial activation was performed at the surgeon’s chairside, immediately following completion of the exposure procedure.

Читать дальше