This method of open exposure surgery will cause the tooth to acquire a new gingival margin, originating from the healed, cut edge of gingival tissue, which will move with the tooth as it is drawn down into its place in the arch. However, while the periodontal parameters may be very satisfactory, at the end of treatment the physical appearance of the tissues surrounding the aligned tooth will not have a completely natural look and it will usually be possible, even several years later, to identify the previously affected tooth with ease.

On the basis of the results of the study of Kokich’s group from the University of Washington, relating to exposure on the buccal side of the ridge, the group questioned the justification for continued use of the apically repositioned flap method [24]. Indeed, it is clear that there are grounds for their scepticism, particularly in relation to canines that are more severely displaced. On the other hand, it should be realized that, for the more trivial cases where the tooth is fairly close to its final mesio‐distal position and is bulging the oral mucosa at its junction with the attached gingiva, the application of the apically repositioned flap method may actually eliminate the need for subsequent orthodontic treatment, while producing a good periodontal result.

Experience has shown that many of these teeth never fully come down to the occlusal level and those that do erupt well may take many months, sometimes stretching to a year or more. This appears to be due to the tendency to relapse, which is engendered by a surgically caused distortion of the mucosal lines in the muco‐gingival area [24]. The overall, final result of this form of surgical exposure may display an unaesthetic gingival contour, requiring remedial grafting [21–25]. If left untreated, buccally palpable unerupted teeth may take many months to break through the mucosa and reach their final positions. The process may be speeded up by performing an apically repositioned flap.

If the unerupted tooth is very high, an apically repositioned surgical flap would need to be larger than usual, since it will need to involve attached gingiva from the crest of the ridge or the free gingiva of the deciduous tooth, to the height of the labial vestibular sulcus. In such circumstances the procedure is not recommended, since the flap would leave a wide area of periosteum of the labial bony plate unnecessarily exposed to the oral environment. This would result in the need to cover this area with grafts harvested from elsewhere in the oral cavity.

One convenient, alternative procedure for these very high teeth that we have described is to use the two separate techniques in sequence [26]. This would also be appropriate for conditions such as the labial dilacerated central incisor. The first stage is to use the closed eruption exposure procedure, including attachment bonding, to bring the tooth down until it is well above the attached gingiva, bulging the labial mucosa. Only at that point will the apically repositioned flap be used, with the flap being taken over the incisal edge/occlusal tip of the tooth and sutured on its labial side. The tooth will continue to be drawn occlusally, completely encompassed by firm gingival tissue. In addition, a well‐sutured flap will apply pressure on the labial side of the buccally/labially displaced tooth, which will become a positive influence in moving it lingually towards the general line of the dental arch (see Chapter 15).

An important advantage of the apically repositioned flap method is that the buccally impacted canine is exposed to the oral environment and remains accessible for attachment bonding. Sometimes the progress of the tooth may be monitored for many months, without orthodontic assistance or appliances, until full eruption has occurred ( Figure 5.1). At an appropriate later date, an attachment may be bonded by the orthodontist and active extrusion may subsequently be undertaken.

The closed eruption technique

The contrasting approach to surgical exposure is the closed eruption technique. This technique involves an orthodontic attachment bonded at the time of the exposure, with the tissues being fully re‐sutured back to their former place, thereby re‐covering the impacted tooth. The technique was first described by Hunt [27] and McBride [4, 5, 28] and is a procedure that may be used regardless of the height or mesiodistal displacement of the tooth.

In the case of a buccally impacted tooth, a surgical flap is raised from the attached gingiva at the crest of the ridge, with appropriate vertical releasing cuts, and is elevated as high as is necessary to expose the unerupted tooth. An eyelet or button attachment is then bonded and the flap fully sutured back to its former place [7]. The twisted stainless steel ligature wire (or gold chain, as preferred by some clinicians), which has been tied or linked to the attachment, is then drawn inferiorly through the sutured edges of the fully replaced flap. The surgical wound is thereby completely closed and the impacted tooth with its new bonded attachment is sealed off from the oral environment. Because it is fully closed, spontaneous eruption will not occur. Accordingly, active orthodontic force will need to be applied to the tooth to bring about its eruption [29]. In the following period of several weeks or months and after complete healing of the repositioned surgical flap has occurred, the tooth will progress towards and through the area of the attached gingiva and will create its own portal, through which it will exit the tissues and erupt into the mouth. In so behaving, it very closely simulates normal eruption and results in a similar clinical outcome in terms of its clinical appearance and objective periodontal parameters. It will usually be difficult to distinguish from any normally and spontaneously erupting tooth.

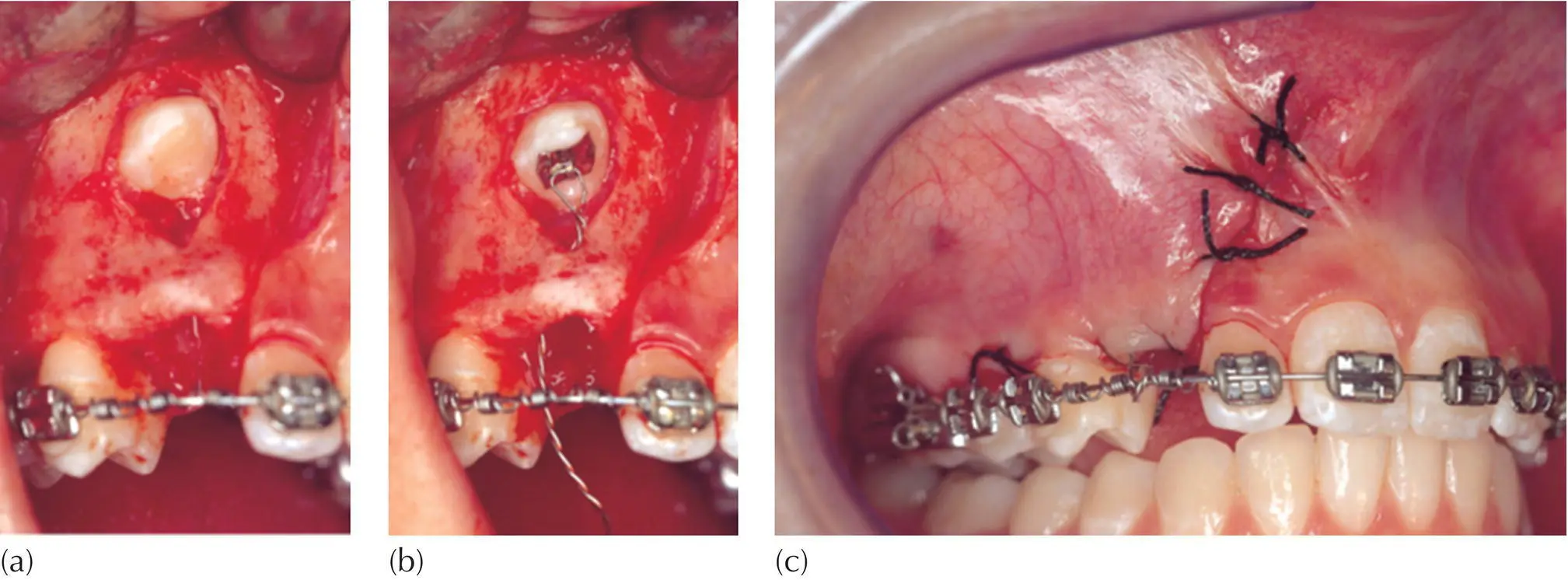

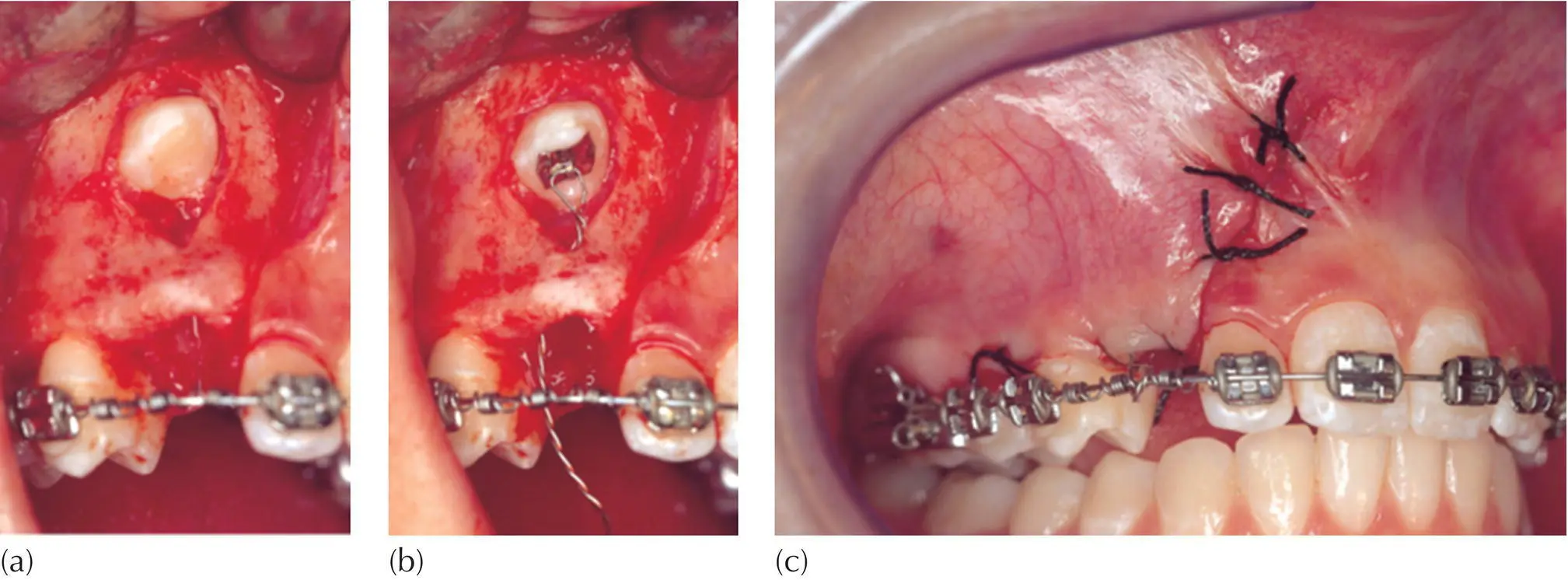

Crescini et al. [30] described a modification of the closed eruption technique, which they called the ‘tunnel’ technique, specifically relating to maxillary permanent canines. The aim of this aptly named method is even further to mimic the natural eruption process by applying extrusive force to move the impacted canine directly through the socket of the recently extracted deciduous canine ( Figure 5.5). In this procedure, a full buccal flap is raised from the attached gingiva at the neck of the deciduous canine and adjacent teeth, in order to expose the surface of alveolar bone, and the deciduous canine is extracted. The twisted steel ligature or gold chain, which is linked to the bonded eyelet, is then threaded into the apical area of the newly vacated socket of the deciduous canine and drawn downwards to exit through its coronal end. No buccal bone need be removed beyond that immediately overlying the crown of the exposed canine. The flap is then sutured back to its former position, leaving only the end of the ligature/gold chain visible through the socket of the deciduous canine.

Fig. 5.5 Crescini’s tunnel variation of the closed eruption technique. (a) A very high labial canine was exposed with a full‐flap exposure, which included the gingival margin of the extracted deciduous canine. The canine was exposed and, below it, a bridge of buccal bone was left intact. (b) An attachment was bonded to the palatal aspect of the permanent canine and its pigtail ligature directed through the socket vacated by the extracted deciduous tooth. (c) The flap was sutured to its former place and vertical traction drew the tooth down, retaining the alveolar bone on its labial side.

Courtesy of Dr E Ketzhandler.

It will, however, be quite clear that this method is only indicated when the crown of the permanent canine is at a significant distance above and directly superior to the apex of the deciduous canine and when its orientation is close to the vertical. It cannot be employed when there is mesial or distal displacement of the impacted canine, overlapping the adjacent lateral incisor or the first premolar. Neither is it appropriate when the tooth is more than slightly palatal to the line of the arch.

Читать дальше