Eliminating the follicular sac completely, down to the cemento‐enamel junction (CEJ) area.

Removing all bone around the tooth, down to the CEJ area, in order to dissect out and free the entire crown up to the coronal portion of the root of the impacted tooth.

‘Loosening’ the tooth by luxating it with an elevator or extraction forceps.

Bone channelling in the direction of the desired movement of the tooth.

Packing gauze or heat‐softened gutta percha into the area of the CEJ, under pressure, in order to apply force to deflect the eruption path of the tooth in the preferred direction.

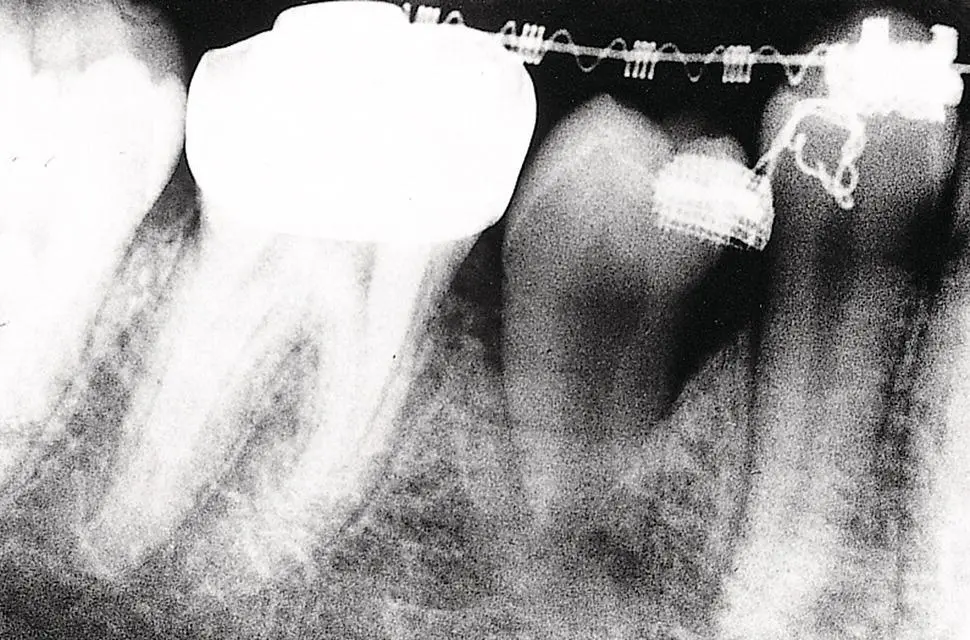

Back in the early 1970s, it was rare that the general dentist referred such patients to the orthodontist, at least not before full eruption had been achieved and then only to assist in moving the tooth horizontally into line with its neighbours. Before full eruption took place, the problem was considered to be within the realm of the oral surgeon. In many cases, ‘success’ in achieving the eruption of the tooth was indeed pyrrhic and sometimes actually caused a greater problem, particularly in relation to the periodontal condition of the newly erupted tooth and its survival potential – namely, its prognosis. This most unfortunate consequence was the result of the aggressive and overenthusiastic surgical techniques that were then being used, most of which typically left the tooth with an unaesthetic and elongated clinical crown, a lack of attached gingiva and a reduced alveolar crest height [9–13]. Just occasionally, these damaging procedures initiated an invasive cervical root resorption lesion, which created a state of non‐response to orthodontic traction and failure in generating its eruption.

Surgical intervention without orthodontic treatment

Notwithstanding my description in the first part of this chapter, there are situations and conditions in which surgical intervention without orthodontic treatment is called for and indeed appropriate. Thus, in cases in which the impacted tooth is the only clinical problem (the occlusion and alignment being otherwise acceptable), the question that needs to be addressed is: what surgical methods are available that may be expected to provide a more or less complete solution without orthodontic assistance? In order to discuss this question, it is necessary to provide a description of the position of the impacted tooth that is being encouraged to respond to this kind of treatment.

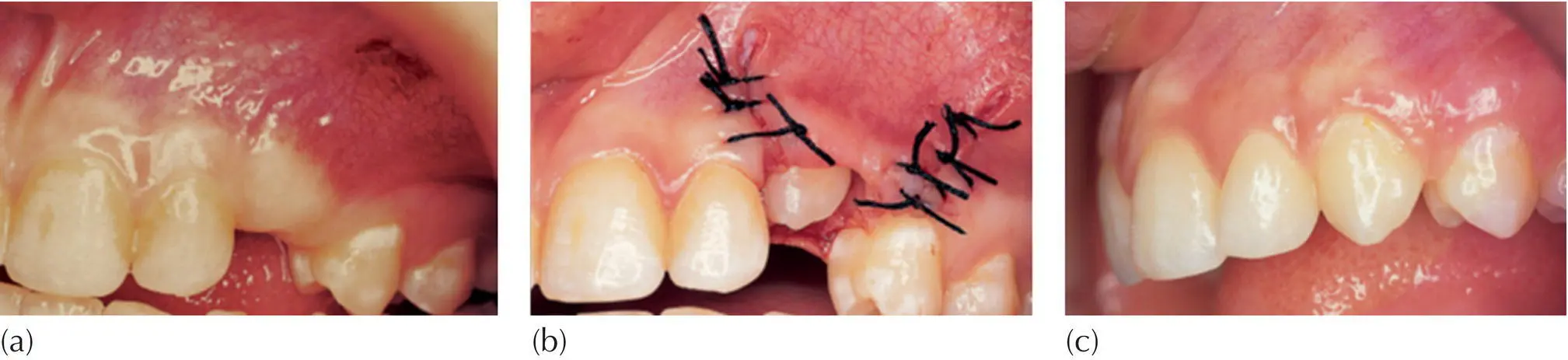

The most obvious example is a superficially placed tooth, palpable beneath the bulging gum. This type of impaction may be found in relation to the maxillary canine ( Figure 5.1), or in the mandibular premolar area (see Figure 1.8) or even the maxillary central incisor. The usual cause of this condition is where very early extraction of the deciduous predecessor was performed while the immature permanent tooth bud was still deep in the bone, with as yet inadequate eruption potential. Healing then took place, the gum closed over and the permanent tooth was unable to penetrate the thickened mucosa. Removing the fibrous mucosal covering or incising and re‐suturing it to leave the incisal edges exposed ( Figure 5.2a–c) will generally lead to a fairly rapid eruption of the soft tissue impacted tooth, particularly in the maxillary incisor area. The more the tooth bulges the soft tissue, the less likely will be a re‐burial of the tooth during healing of the soft tissue, with the consequent rapid eruption of the tooth.

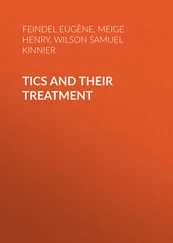

Fig. 5.1 (a) A 16‐year‐old female exhibits an unerupted maxillary left canine, which has been present in this position for two years and has not progressed. (b) The tooth was exposed and the flap, which consisted of attached gingiva, was apically repositioned. (c) At nine months post‐surgery, the tooth has erupted normally, without orthodontic treatment.

Courtesy of Professor L. Shapira.

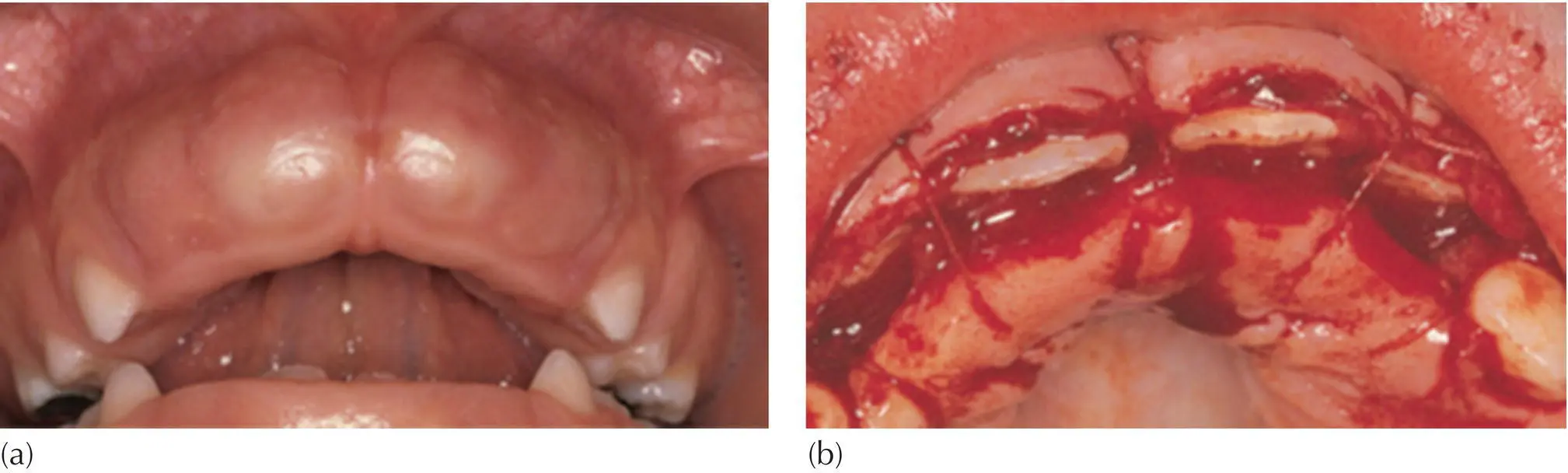

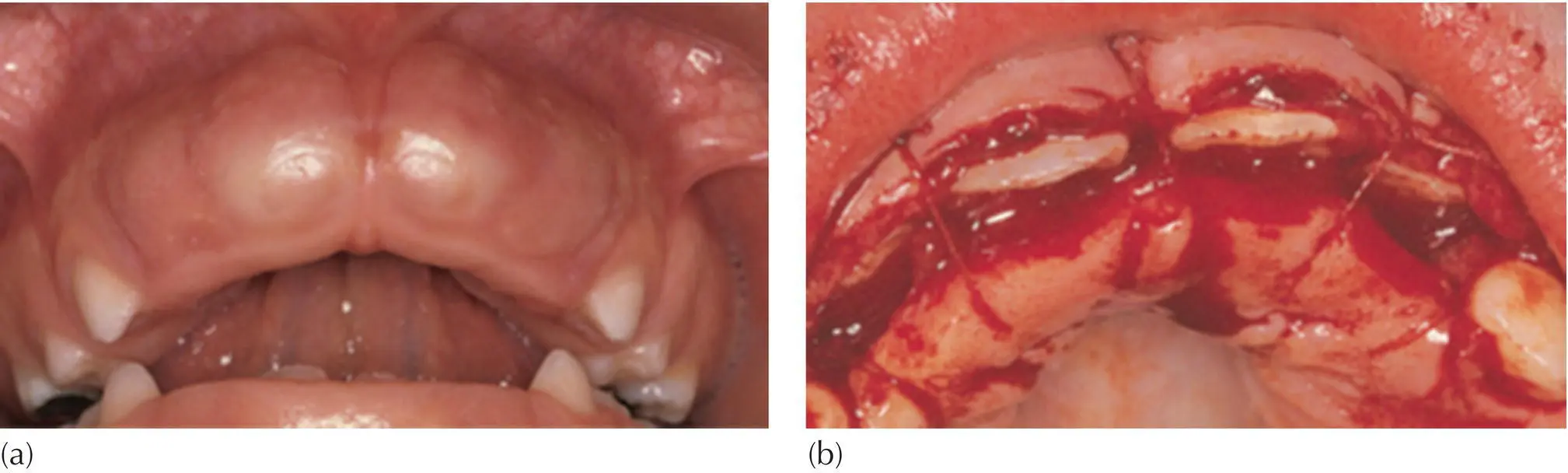

Taking this one step further, it is clear that an impacted tooth that is buried much deeper in the alveolus will be much more prone to being re‐enveloped by its surrounding healing tissues. It will require a more radical exposure procedure to ensure its patency. In addition, it may need a pack to hold back the tissues during the post‐surgical days and weeks, in order to ensure subsequent direct access to the tooth. While the surgeon may ultimately be rewarded with spontaneous eruption, this will inevitably take longer and the extent of the surgery may lead to a compromised periodontal result ( Figure 5.3).

Over‐retained deciduous teeth have been defined in Chapter 1as teeth that are still present in the mouth when their permanent successors have reached a stage of root development that is compatible with their full eruption (two‐thirds of expected root length). These deciduous teeth are to be considered as obstructing normal development. While it follows that they should be extracted, provision should be made at the same time to encourage the permanent teeth to erupt quickly.

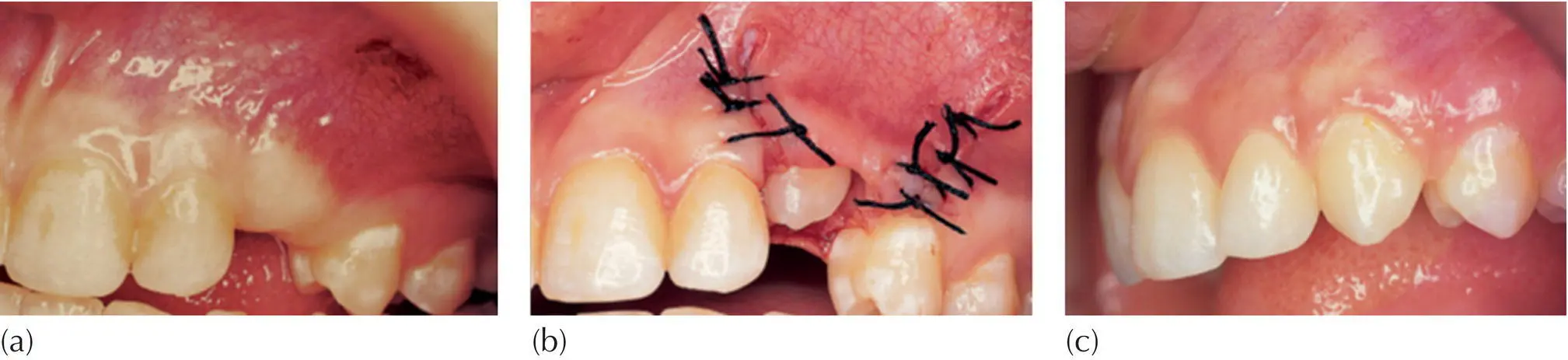

Fig. 5.2 (a) Soft tissue impaction of maxillary central incisors. (b) Apical repositioning of both labial and palatal flaps to leave the incisor edges exposed.

Courtesy of Professor J. Lustman.

Fig. 5.3 Following exposure, attachment bonding and packing the unerupted tooth, it erupted spontaneously, but the bone level was compromised.

Permanent teeth whose eruption has been obstructed or delayed are abnormally situated deep in the alveolus and are in danger of becoming re‐buried by the healing tissue of the evacuated socket of the extracted deciduous tooth. Accordingly, the crowns of the teeth should be exposed to their widest diameter and a surgical or periodontal pack placed over them and sutured in place for 2–3 weeks. This will encourage epithelialization down the sides of the socket and should prevent the re‐formation of bone over the unerupted tooth.

In order to maintain the surgical opening, most surgeons and periodontists today will use a proprietary pack, such as CoePak™, which doubles as a dressing for the surgical wound. Alternatively, particularly with maxillary palatal canines, placement of a removable acrylic plate, which will have been prepared before surgery, can be employed in order to retain a small pack over the exposed tooth [14]. Regardless of the method, however, and parallel with the concern for maintaining the patency of the exposure, one must exercise appropriate concern to hold the space for the anticipated eruption of the impacted tooth. Space loss in the mixed dentition may often be very rapid and may result in halting the progress of the erupting tooth by its proximal contact with the adjacent teeth. It is essential that this aspect be considered and the appropriate provisions made and followed closely.

‘Expose‐and‐pack’ was revived and reintroduced as an approach and has been recommended for the treatment of severely palatally displaced maxillary canines [15]. This method has been recommended as being suitable for spontaneous resolution even in some cases of quite severe displacements. It creates the possibility of at least partial eruption through the surgically created and pack‐maintained opening and permits relatively easy access for attachment bonding. Subsequent alignment of the tooth can then be beneficially undertaken, utilizing simplified appliance therapy. However, validation of the method by a disciplined clinical study has not been done and the evidence in its favour must therefore be considered anecdotal at present.

Читать дальше