Another ongoing revolution of tools is in modern IT equipment and apps, not least, in a specialty so dependent on visual observation and pattern recognition, as a means of instantly sharing images and videos of cases to better indicate clinical findings. Thus, it made sense to develop a library of still and motion images of clinical material to share with readers in this edition of Large Animal Neurology . The video library is not only a compilation of a wide variety of cases we have been fortunate enough to see but, more importantly, provides examples of actions, movements, postures and syndromes, and particularly visual examples to assist in the definition of clinical signs and syndromes such as bizarre behavior, the ataxias, sleep attacks, tetany, and tremor.

As with most clinicians and neurologists, we have likely reviewed thousands of videos and images of clinical cases over the years. Very often, new aspects of a case come to light after multiple viewings at both normal and slow speeds. Similarly, and particularly with cases that are enigmatic or show fluctuating signs, by returning to study the patient or the video, subtle and interesting—and sometimes profound—signs that had not previously been noted become apparent. Typical examples of this include a change in eyelash angle seen in Horner syndrome; brief, repeated, minor facial grimaces of a foal with focal epilepsy; movement of lice toward areas of skin with sympathetic denervation; and reversion from pacing gait at birth, then four‐beat walk at 2 weeks of age, back to a pacing gait before the onset of overt ataxia in a young foal with progressive signs of spinal and other forms of ataxia. One can then approach new cases with this information so that when such “new” signs are present, one will look for them and thus see them. It is worth iterating:

More mistakes are made from not looking than not knowing, and further mistakes are made from not seeing rather than not looking

(Radostits et al ., 2000).

Simply informing a student, at whichever stage of their career, of one’s expert opinion on a case is rarely helpful. As a clinical teacher, one should be prepared to “think aloud” and share the thought processes as to how one is synthesizing the facts of a case to arrive at a particular differential diagnosis and course of action, namely, the diagnostic reasoning used. We have also found two other maxims useful in teaching over the years. First, we should not take ourselves too seriously, we all make mistakes. Second, we need to remember that the next generation in our profession will be better equipped than us; if we can be fortunate enough to contribute to that advancement then so much the better.

Following on from the influence of our learned mentors, we have tended to remain critical of misuse of terminology, particularly regarding anatomic terms. We thus continue to strive to follow both the Oxford English Dictionary (OED, 2009), and particularly the Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria (NAV, 2017).

We humbly acknowledge the instruction, friendship, and encouragement that we have been fortunate to receive and share with colleagues at Massey University (NZ), Guelph University (Canada), the University of California at Davis (USA), the University of Florida (USA), Cornell University (USA), Cambridge University (UK), and the University of Edinburgh (UK). It’s been fun. Quentin Roper again deserves special thanks for his painstaking electronic draftsmanship in preparing many of the drawings in the second edition and again in this edition. Most especially, we are indebted to the many patients that, through their misfortune, taught us neurology.

Our families remain as our sustainers for which we are eternally grateful.

| Joe Mayhew |

Rob MacKay |

| Massey University |

University of Florida |

| New Zealand |

USA |

1 NAV. Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature (ICVGAN). 2017

2 OED. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 2009

3 Radostits OM, Mayhew IG, and Houston DM . Veterinary Clinical Examination and Diagnosis. WB Saunders, London. 2000

About the companion website

Don’t forget to visit the companion website for this book:

www.wiley.com/go/mayhew/neurology

There you will find valuable materials, including:

Video clips presenting a wide variety of diseases that show actions, movements, postures, and syndrome characteristics of the disorders

Figures from the book as downloadable PowerPoint slides

Scan this QR code to visit the companion website

Basic descriptive terminology Functional neuroanatomy

References

Some of the most rewarding aspects of clinical neurology involve being able to associate observed signs and syndromes with neuroanatomic sites of the lesions. This may, for example, be experienced when recognizing a syndrome of ataxia in a purebred patient and associating it with a familial cerebellar disorder for a client. Alternatively, one may be able to explain to a producer how a certain lesion, detected by an astute neurologic examination of one representative animal and confirmed at postmortem examination is the cause of the clinical syndrome observed in the herd. The basic requirement for achieving this degree of diagnostic acumen is an understanding of applied neuroanatomy.

This chapter provides the basic information necessary to allow the clinician to appreciate the fundamentals of a neurologic examination and to interpret, accurately, the results of such an examination. As the clinician becomes adept at these tasks, further anatomic details may be sought. These can be found in the texts listed in the references.

At this point, a plea is made for a clear use of anatomic terms, based on Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, Nomina Embryologica Veterinaria and Nomina Histologica, 1along with the clinically applied terms used in functional neuroanatomy, 2–4clinical neurology, 5–7and veterinary neuropathology. 8–10

Basic descriptive terminology

The following is a review of basic descriptive terminology; note that the derivation, abbreviation, combining form, synonym, or explanation is given parenthetically.

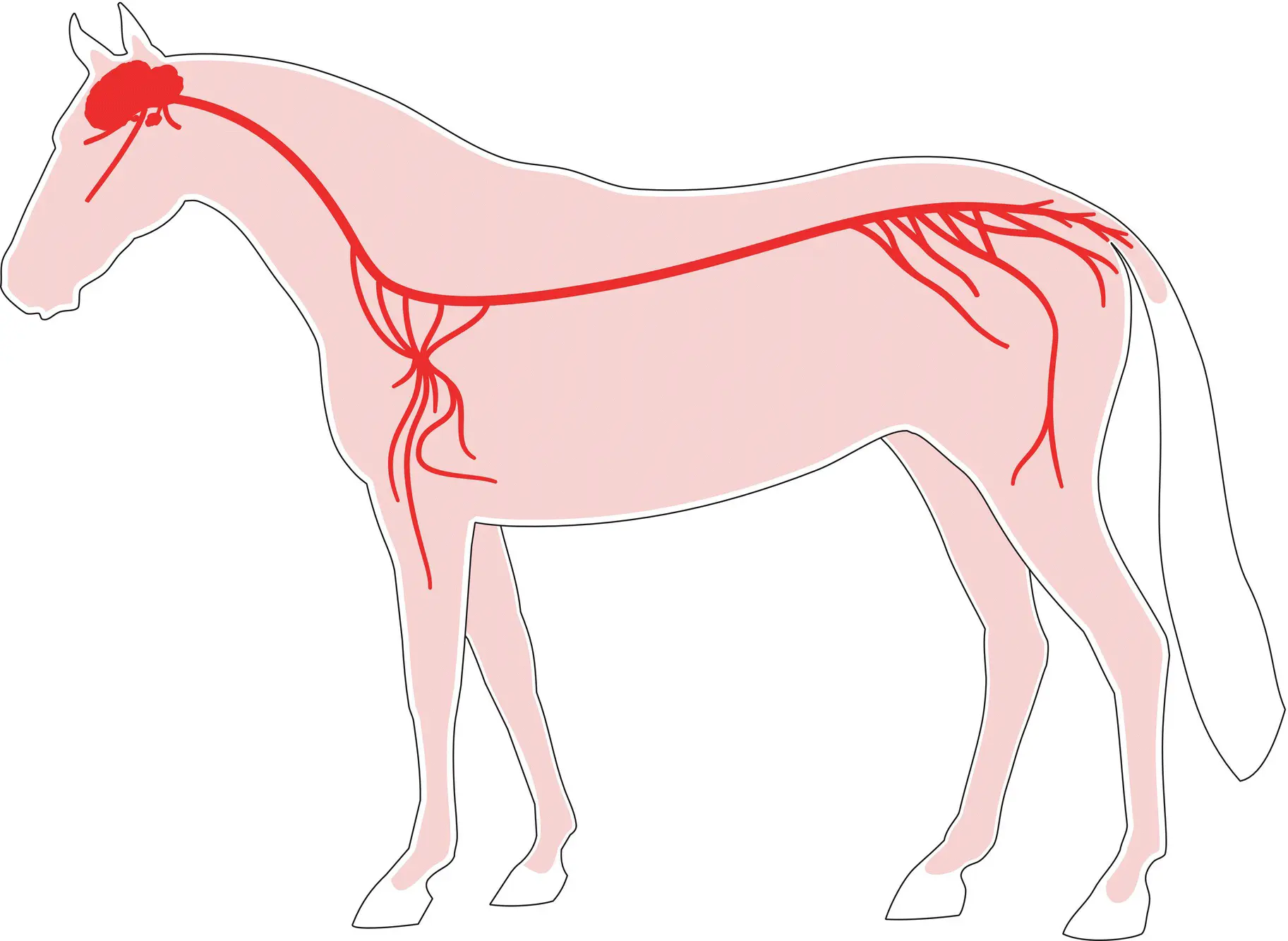

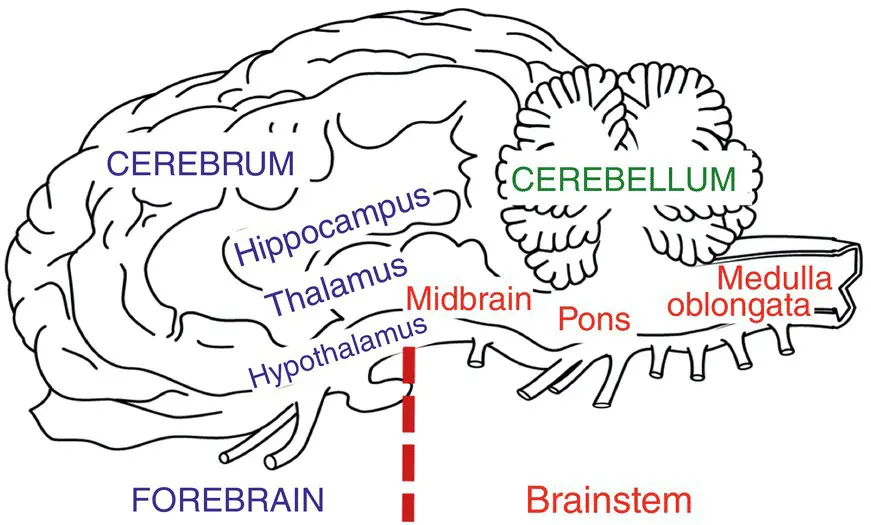

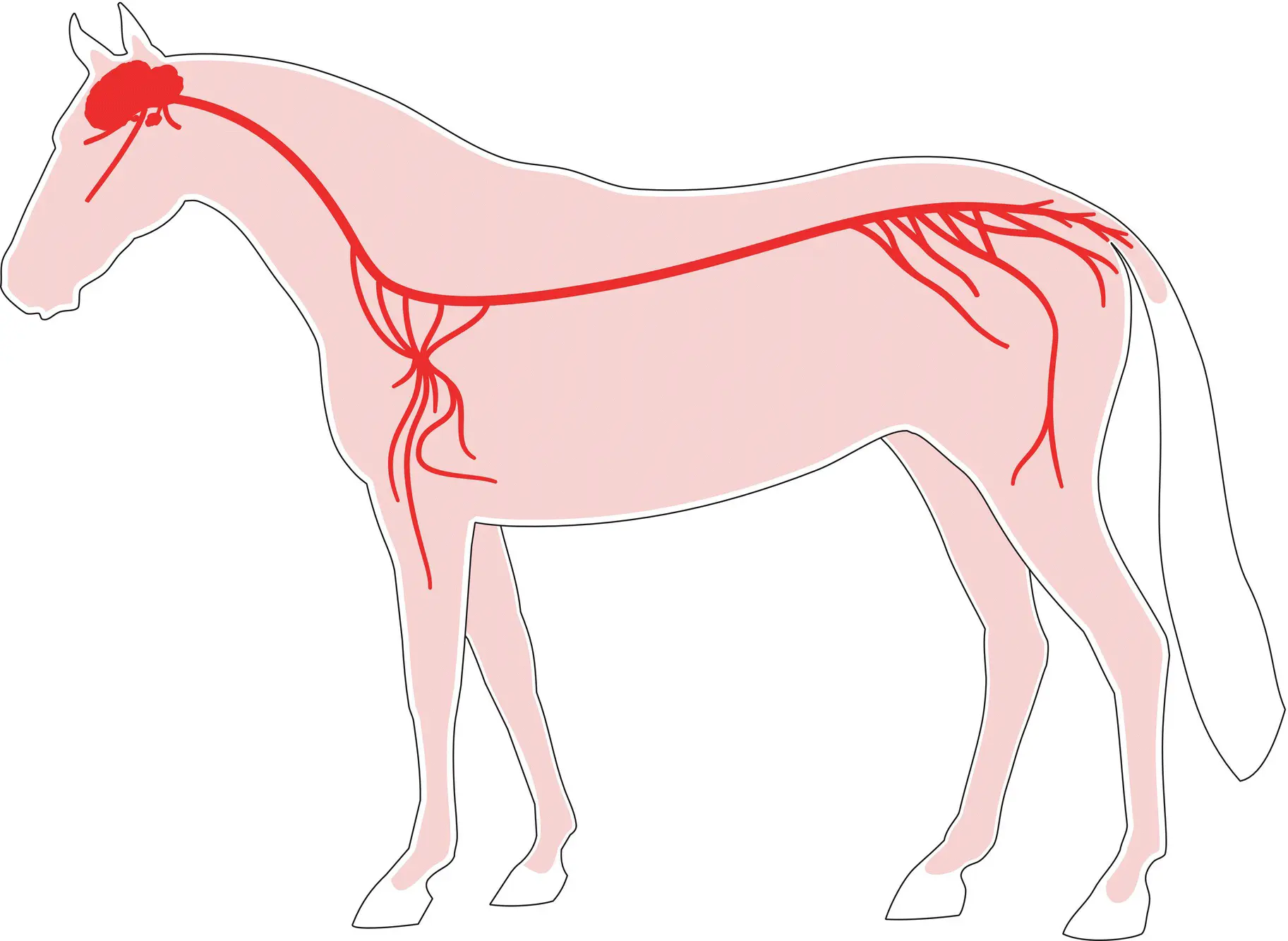

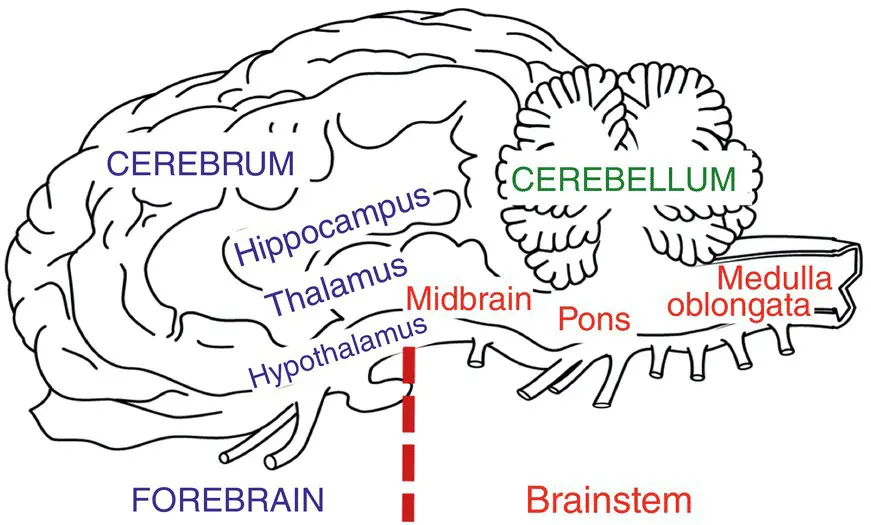

The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain (encephalo) ( Figure 1.1) and spinal cord (myelo). It contains collections of neuronal cell bodies or somata in layers (laminae), nuclei, and columns of gray matter (polio). Tracts, sheets, and pathways of dendritic (afferent) and particularly axonal (efferent) processes of these cell bodies make up the white matter (leuko). These processes make up most of the CNS along with their fatty, myelin (myelino) coats. In tall, large animals, some of these neuronal fibers extend 2–3 m, and many exit and enter the CNS via the cranial and spinal nerves of the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

Figure 1.1 Basic areas of the brain can be readily recognized on this diagram of a median section of a horse brain. The terminology used in this book is shown. Wherever possible the authors use the terminology of Nomona Anatomica Veterinaria ;

Читать дальше