The good news is that it doesn’t take much effort to reverse the deleterious effects of touch deprivation on infants. In understaffed orphanages, twenty to sixty minutes per day of gentle massage and limb manipulation was able to mostly reverse the negative consequences of touch deprivation. The babies receiving touch therapy gained weight more quickly; had fewer infections, better sleep, and decreased crying; and progressed more rapidly in developing motor coordination, attention, and cognitive skills.

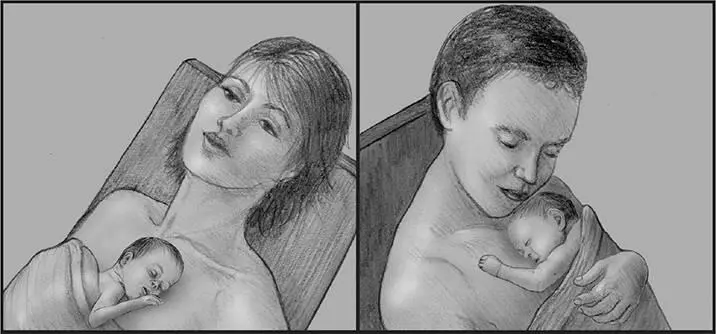

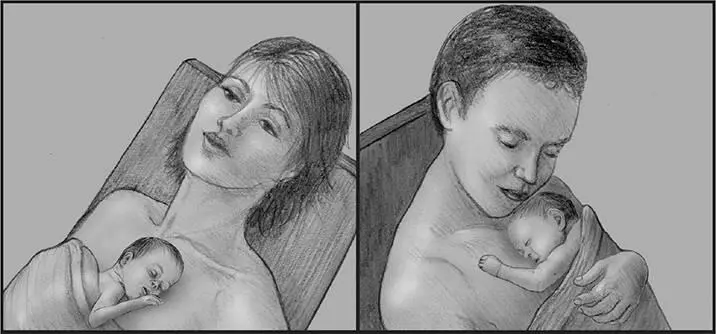

For preterm babies, one of the effective methods of delivering gentle tactile stimulation is called kangaroo care. This technique was developed out of necessity in an overcrowded neonatal intensive care unit at the Instituto Materno Infantil in Bogotá, Colombia. In 1978 Dr. Edgar Rey Sanabria was dealing with a terrible 70 percent mortality rate in this unit, mostly from respiratory problems and infections. There were insufficient doctors and nursing staff and not enough incubators. Dr. Sanabria encouraged mothers to devote many hours a day to skin-to-skin contact with their preterm infants to keep them warm and to provide breast-feeding on demand. The typical position used was chest-to-chest with an upright posture, inspired by the skin-to-skin contact of a mother kangaroo with a joey in her pouch. Tactile stimulation was not the main rationale for kangaroo care but turned out to be one of its primary benefits. Introduction of this method rapidly reduced the mortality rate at Sanabria’s unit to 10 percent. Kangaroo care, which is inexpensive and enormously effective, has spread and positively transformed neonatal care around the world (figure 1.6). 22One recent study followed two groups of preemies, one that received kangaroo care for fourteen consecutive days after birth and another that received standard incubator care. Impressively, clear benefits of early skin-to-skin contact could still be seen at age ten. The kangaroo care preemies grew up to be less stress-reactive and to have improved sleep patterns, cognitive control, and mother-child reciprocity. 23

Figure 1.6Kangaroo care for preterm infants. The baby wears only a diaper (and sometimes a hat) to maximize skin-to-skin contact. Mothers provide most kangaroo care, but fathers can pitch in as well. Today, more than 80 percent of neonatal intensive care units in the United States utilize kangaroo care, largely due to the effective proselytizing efforts of Susan Ludington, a professor of pediatric nursing at Case Western Reserve University.

We know from our own everyday social experiences that touch can be used together with other sensory signals to communicate a broad range of emotional intentions including support, compliance, appreciation, dominance, attention getting, sexual interest, play, and inclusion. These intentions have been documented in self-report studies in which participants were instructed to write down a brief note immediately after they touched someone or were touched themselves. 24While self-reports have the advantage of analyzing behavior that occurs out in the world, where life is lived, they also have the disadvantage that all the wonderful multisensory and situational complexity of the real world makes it hard to tease out the precise role of touch in any given interaction.

Let’s dig a little deeper. Can touch communicate specific emotions, or does it merely intensify emotions primarily conveyed by other senses, like sound or sight? Or, perhaps, the answer lies somewhere in the middle: Touch might convey emotions, but only generally, and is limited to signaling and overall tone: warmth/intimacy/trust versus pain/discomfort/aggression. Matthew Hertenstein of DePauw University and his colleagues have begun to conduct some interesting experiments to address the role of social touch in emotional communication. 25In one study, pairs of students at a university in California sat at a table and were separated by a black curtain. They were not allowed to see each other or talk at any point. One subject, designated as the encoder, was shown a sheet of paper containing a word defining an emotion, selected randomly from a list of twelve. He or she was asked to think for a moment about how to communicate that emotion and then to attempt to convey it by touching the bare forearm of the other subject in any appropriate way for about five seconds. The receiving subjects, or decoders, could not actually see the touch because their arms were placed on the encoder’s side of the curtain. After each touch, the decoder was asked to score the intention of the encoder on a response sheet consisting of the twelve possible emotion words (anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, sympathy, embarrassment, love, envy, pride, and gratitude) listed in random order together, as well as the choice “none of these terms is correct.” All the touches were recorded on video and evaluated later by others who had no knowledge of either the intended or received emotion.

When data from 106 pairs of subjects were analyzed, it was found that the self-focused emotions of embarrassment, envy, and pride were not effectively communicated, but that the prosocial emotions of love (encoded mostly by stroking and finger interlocking), gratitude (handshaking), and sympathy (patting and stroking) were decoded at levels well above chance. When examining a set of emotions shown by other investigators to be readily conveyed by facial expressions, 26anger (encoded by hitting or squeezing), fear (trembling, squeezing), and disgust (pushing away) were successfully conveyed, but happiness, sadness, and surprise were not. Later, at a separate location, another group of subjects was asked to score videotapes of these touches using the same list of twelve emotions plus the option “none of the above.” They, too, were able to decode love, gratitude, sympathy, anger, fear, and disgust at high rates, but not the other emotions. The researchers concluded that humans could indeed communicate distinct emotions through touch and thereby argued that touch is not limited to intensifying or shading the meaning of emotions primarily conveyed by other senses.

As always, though, the devil is in the details. Of course, ideas and expectations about touch differ across cultures, in specific interactions between the genders, and even in particular situations, and these variables can influence touch communication. When the anonymous arm-touch experiment was repeated in Spain, the results were almost identical. However, when Hertenstein and coworkers reexamined their data set from the Californian anonymous touch subjects several years later, some interesting gender effects emerged. 27When a woman attempted to convey anger to a man, he never decoded the touch intention accurately. And when a man tried to convey sympathy to a woman through anonymous touch, she was never able to interpret the message.

These anonymous-touch laboratory experiments are useful in defining the boundaries of what touch can communicate in isolation, but, of course, no one actually uses touch to communicate in comparable conditions in real life. First, most touch communication does not take place between strangers—in most cases it’s a more intimate form of interaction. Second, touch in the real world is never devoid of context. We know from our own experience that the very same touch sensation can convey a very different emotional meaning, depending on the gender, power dynamic, personal history, and cultural context of the touch initiator and receiver. An arm around the shoulder can convey a variety of intentions, ranging from group inclusion or sympathy to sexual interest or social dominance. 28And, of course, the cultural influence on social touch, particularly public touch, is enormous. In the 1960s, the psychologist Sidney Jourard observed pairs of people engaged in conversation in coffee shops around the world. 29He methodically watched the same number of pairs in each location for the same amount of time. Jourard found that couples in San Juan, Puerto Rico, touched an average of 180 times per hour, compared with 110 times per hour in Paris, 2 times per hour in Gainesville, Florida, and 0 times per hour in London. 30Similar differences were seen when touches were scored among people of twenty-six different nations in the departure lounges of an international airport on the West Coast of the United States. 31Public farewell touching was most common among people born in the United States, in the Latin/Caribbean region, and in Europe, and was much less common among people born in northeast Asia.

Читать дальше