So the situation is not dissimilar for human NBA players and certain nonhuman primates like gelada baboons: Social touch tends to reinforce cooperation and loyalty. Human and nonhuman primates alike use grooming and other forms of social touch to soothe, reconcile, form alliances, reward cooperative actions, and reinforce bonds of kinship and friendship. Has this type of behavior appeared only in the primate lineage, or are there traces of it in other animals as well?

There is at least one notable example of social grooming and cooperation in a nonprimate. The common vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus , takes wing at night to feed on the blood of living mammals, most commonly horses, burros, cattle, and tapirs. This is their only food source, because their narrow throats cannot accommodate solid food. If the animal they are feeding upon has fur, they will use their canine and cheek teeth to carefully shave away a patch prior to piercing the skin with sharp upper incisors to start bleeding. The bats’ saliva contains an anticoagulant compound that keeps the blood flowing for the twenty to thirty minutes of lapping needed to consume a meal. (Sometimes another bat will wait patiently to feed at the same wound.) An adult female vampire bat typically weighs about 40 grams but can consume a blood meal of 20 grams before flapping away, laden and sated. However, vampire bats have a very high metabolism, and if they fail to find a meal on two successive nights, they will lose about 25 percent of their body weight and be near death.

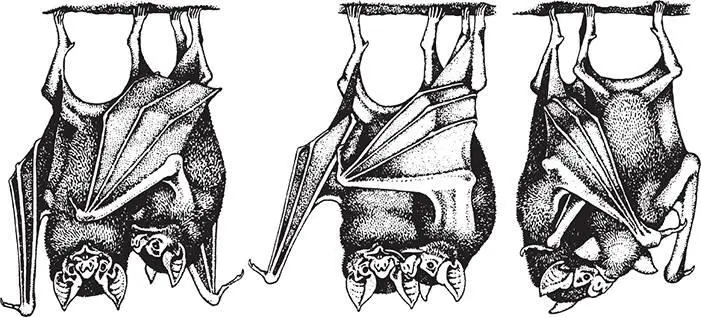

In one part of their range, in northwestern Costa Rica, vampire bats live in hollow trees in groups of eight to twelve. Gerald Wilkinson and his colleagues from the University of Colorado observed these bats in their tree roosts every day for many months. 13They found that the animals were more likely to groom each other if they were closely related or if they were frequent roost mates. Grooming also promoted cooperation of a particular kind: A bat that was just groomed was more likely to share a blood meal with its groomer through regurgitation (figure 1.4). In fact, the grooming seemed to function as a type of solicitation for food sharing. By begging food from a roost mate who has just returned from feeding, a bat can fend off starvation for one more night, and so have a chance to find its own blood meal. In the vampire bat world, this is what counts as a win-win deal: I’ll groom you, and you’ll vomit blood down my throat. Next time, in the spirit of reciprocity, maybe I’ll do the same for you.

Figure 1.4A hungry bat solicits regurgitated blood by grooming. The grooming starts with the hungry bat licking the potential donor under her wing (left), and then licking the donor’s lips (center). If receptive, the donor responds by regurgitating blood (right). Only bats that are close relatives or exhibit long-term roosting associations provision blood to one another. Illustration by Patricia J. Wynne; used with permission. This drawing first appeared in G. S. Wilkinson, “Food sharing in vampire bats,” Scientific American 262 (1990): 76–82.

We’ve seen a lot of evidence that social touch can promote trust and cooperation. Underlying our interpretation of these findings has been the presumption that all these mammals—geladas and humans and bats alike—shared an early experience of a mother’s touch that caused them to associate warm, gentle social touch with safety. What happens when this early maternal experience is lacking?

In the late 1950s Seymour Levine and his coworkers at the Ohio State University Health Center studied the role of early postnatal life on the development of personality, particularly stress responses. They bred Norway rats in the lab, and soon after birth would pick three pups from a litter (which typically consists of ten to twelve pups) and handled them gently for fifteen minutes. This procedure would be repeated every day with the same three pups until they were twenty-one days old. When these handled pups grew into adults, they exhibited a set of positive behavioral traits: They were less fearful, more likely to explore novel environments, and less responsive to stress when compared with their nonhandled littermates. When blood samples were taken from adult rats that had been handled as pups, it was found that brief exposure to stress in adulthood evoked in them a lower secretion of the stress hormones ACTH and corticosterone. 14

These initial studies did not address the means by which handling actually triggered the behavioral and hormonal changes in stress response. Levine suggested that it was not the handling per se that caused the changes but rather the subsequent behavior of the mother rat. When the pups were returned to their home cage after handling, they emitted ultrasonic cries, and in response the mother rat doubled her rate of licking and grooming them. This increased tactile attention persisted throughout the period in which the pups were handled.

While the behavior of mother rats is fascinating for its own sake, we’d ultimately like to know if the lifelong reduction in stress responses of human-handled rat pups is relevant for human development. Interest in this question was sparked by a key set of experiments from a research team at McGill University headed by Michael Meaney. These revealed that if you examine many rat mothers (all Norway rats of the same laboratory strain, called Long-Evans), some lick and groom their pups a lot, while others do less. In fact, the most attentive mothers spent about threefold more time licking and grooming than the least attentive mothers. Furthermore, human handling of the pups could normalize this variation: Following handling, the low licking-grooming mothers increased their pup licking-grooming time to match that of their most attentive peers. 15

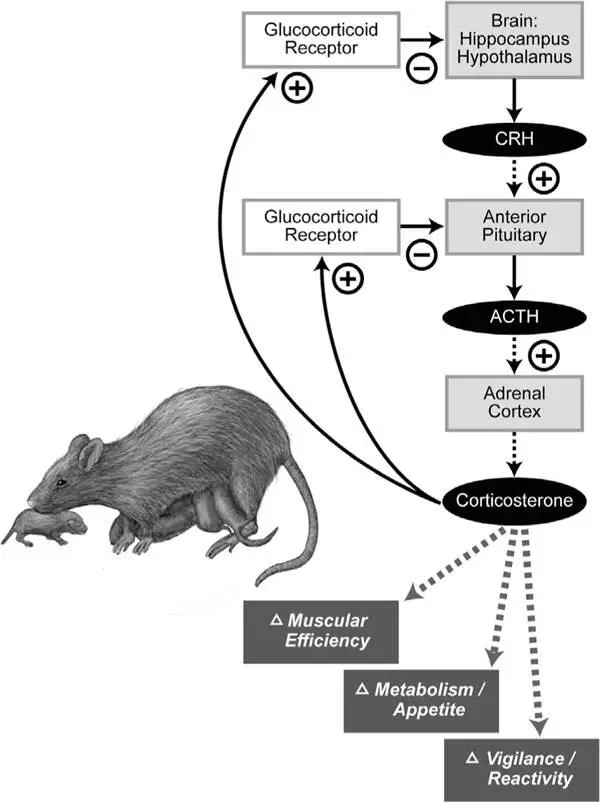

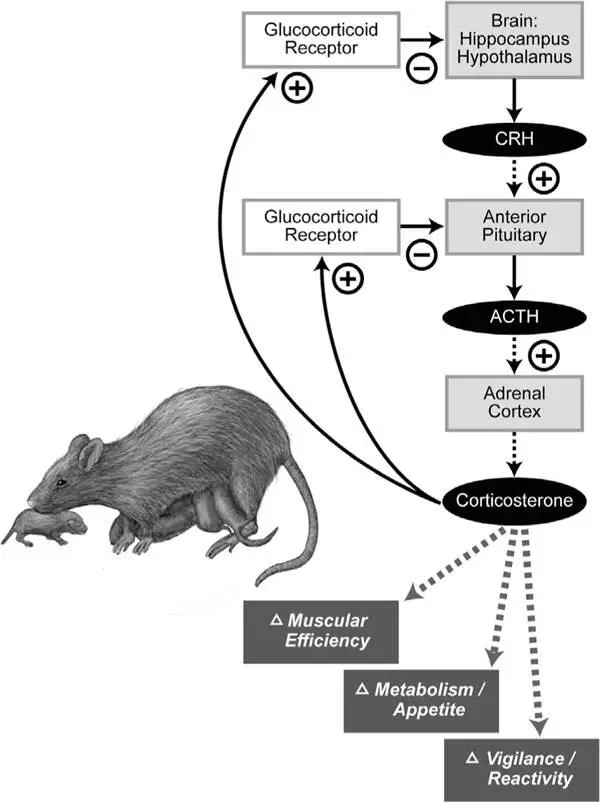

When the pups of low licking-grooming mothers grew up, they had impaired spatial learning and more fearful behavior compared to those of high licking-grooming mothers. They were also less likely to explore a new environment or try a new type of food. 16To be a bit anthropomorphic about it, they were wimps. Their fearful behavior can be related to stress-hormone signaling: Adult rats that were offspring of low licking-grooming mothers had lifelong increases in hormonal responses triggered by stress (figure 1.5).

What conclusion should we take from the correlation between low licking-grooming mothers and increased stress responses in their pups? Does low licking-grooming behavior cause these effects, or is it merely correlated with them? Might low licking-grooming mothers pass these traits on to their pups genetically? And there was another twist in these experiments’ findings: In an echo of humans, where poor parenting is often observed across generations, when female pups of low licking-grooming mothers grew up, they were much more likely to become low licking-grooming mothers themselves.

Figure 1.5Maternal licking and grooming of newborn rat pups produces lifelong changes in stress hormone signaling. Stress produces a cascade of hormonal responses that begin in a region at the base of the brain called the hypothalamus, which secretes a hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH activates the anterior portion of the pituitary gland, which in turn secretes another hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which passes throughout the bloodstream to stimulate the adrenal gland. Then the adrenal gland releases the hormone corticosterone, which has many effects on the body, including regulation of muscular efficiency, metabolism, electrolyte balance, appetite, and vigilance. Corticosterone also binds glucocorticoid receptors in the brain to form a negative feedback loop, suppressing production of CRH. This entire stress-signaling pathway is called the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis. Pups of low licking-grooming mothers grow up to have increased levels of ACTH and corticosterone following brief mild stress. (Adult rats were confined to a plastic tube for twenty minutes, following which blood samples were taken.) The brains of these pups also have fewer glucocorticoid receptors available to bind circulating corticosterone, thereby blunting the negative feedback loop and further increasing stress hormone effects.

Читать дальше