Pain and negative emotion are deeply intertwined. In everyday usage we speak of social rejection by peers, family, or even strangers as “hurtful” and rejection in love as “heartbreak.” You’ll recall that this is not our first foray into tactile metaphors. We’ve examined how the sense of touch is intrinsically emotional (feelings!) and how social warmth and physical warmth are interrelated. In the cases of cool mint and hot chili peppers, we’ve even seen how the metaphor is encoded in the sensor molecules TRPM8 and TRPV1.

We know that pain perception has an anatomically distinct emotional component that can be disrupted by damage to the insula or the anterior cingulate cortex. But what exactly is the relationship between physical and emotional pain? There are some suggestive correlations. Studies have shown that those individuals whose feelings are easily hurt, particularly from social rejection, also tend to rate physical pain as more unpleasant when tested in the laboratory. And even in people whose feelings are not easily hurt, experiences that heighten social distress can increase the perceived unpleasantness of physical pain. Surprisingly, analgesic drugs—even fairly mild ones like acetaminophen (Tylenol)—can reduce social pain. But perhaps the most compelling finding is that social rejection and physical pain activate overlapping regions of the brain’s emotional pain circuit: When subjects are excluded from participation in a virtual ball-throwing task on a computer, even this mild form of social ostracism produces activation of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the anterior insula. Another study analyzed a much more potent form of social rejection: When people who had recently been dumped were asked to look at a photo of their former beloved, not only were emotional pain centers engaged but, in addition, the secondary somatosensory cortex, a sensory-discriminative pain center, was also activated. 34

Once again, everyday language is reflective of neural processes. The similarity of emotional pain and physical pain is not merely a construction of evocative or poetic speech. The metaphor is real and it is encoded in the brain’s emotional pain circuitry. Social rejection hurts.

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Itchy and Scratchy Show

Semanza lived in the Rukungiri district of rural Uganda. He suffered such unbearable itching that continuous scratching with his fingernails did not afford him even temporary relief. His solution was to break a clay pot and use the rough edge of one of its pieces as a scratching tool. Eventually his skin became severely damaged and infected with bacteria. Years of relentless itching and scratching had left it so calloused that syringe needles could not penetrate it. Moses Katabarwa, an epidemiologist and health worker at the Carter Center’s River Blindness Program who met Semanza in 1992, said that his skin appeared to be covered in dried mud. No one from his village wanted to be near him, and so Semanza, shunned, lived in a small hut behind his family’s home.

The source of Semanza’s unbearable itch was onchocerciasis, infection with a parasitic roundworm called Onchocerca volvulus . Because this infection can sometimes target the eye and the optic nerve, it is also known as river blindness. This worm is transmitted in larval form by the bite of a black fly that thrives amid fast-moving tropical streams. The disease is not directly produced by the worm but rather by a bacterium that dwells in the gut of the worm and is released when the worm dies, triggering an immune reaction by the human host.

About 18 million people have contracted onchocerciasis, almost all of whom live in Africa, with a few scattered cases in Venezuela and Brazil. Onchocerciasis is not fatal but it results in a miserable life. The disease has blinded about 270,000 people alive today. In Liberia, infected workers on a rubber plantation have been known to place their machetes in a fire pit and then use the red-hot blades as a tool to relieve the relentless itching. Of course the itching also makes sleep elusive, and as Moses Katabarwa explains, “Children with the worms can’t concentrate because they are scratching themselves all day and night.” Suicide is common among its victims.

While there is no vaccine for onchocerciasis, it can be controlled with a drug called ivermectin, which has been donated worldwide by the pharmaceutical firm Merck since 1985. Treatments with ivermectin every six months kill newborn worms (called microfilariae), which releases the itch-triggering bacteria in their guts all at once. While this results in a two-day-long bout of itching that is even more excruciating than that in a normal case, sweet relief follows this brief episode. Semanza was fortunate to receive ivermectin in a locally administered program initiated by Katabarwa. Two years after he began treatment the itching was gone, his skin was partially healed, and he was reintegrated with his community, married, and hoping to start a family. 1

Itching can be a brief sensation or it can last for days. In the case of untreated onchocerciasis, it can endure for a lifetime. It can be triggered by mechanical stimuli, like a wool sweater or the subtle movements of an insect’s legs over the skin, or by chemical stimuli, like the poison ivy inflammatory agent called urushiol. 2Itching can also result from damage to sensory nerves or the brain. In some cases it can be triggered by brain tumors, viral infection, or a mental illness like obsessive-compulsive disorder. It’s also a well-known side effect of certain therapeutic and recreational drugs.

Itching is highly subject to modulation by cognitive and emotional factors. One night, camping in the Amazon jungle, I was just drifting off to sleep when I felt an itchy sensation on my arm. I got my flashlight and glasses, saw what was causing it, and brushed off a huge millipede. At that point, sleep became impossible. I had become hypervigilant, and every little breeze and twitch evoked a sensation of itch for the rest of the night, and not just on the affected arm but all over my body. I was battling millipedes of the mind until dawn.

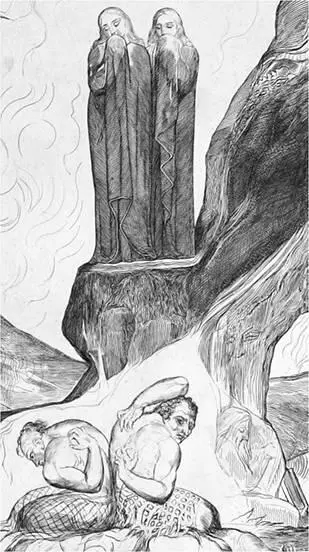

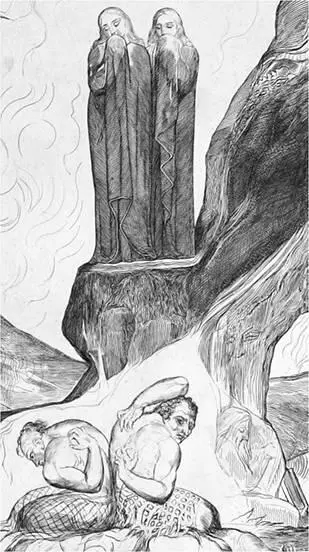

The compelling, tormenting nature of itch is well known. In Dante’s Inferno , falsifiers (including alchemists, impostors, and counterfeiters) were cast into the Eighth Circle of Hell, where they suffered eternal itch (figure 7.1). Only those who committed treachery—fraudulent acts between individuals who shared special bonds of love and trust (like Judas Iscariot, the betrayer of Jesus Christ)—met a presumably worse fate in the Ninth Circle of Hell: being frozen in ice.

Figure 7.1This 1827 illustration by William Blake shows falsifiers being tormented by eternal itch in the Eighth Circle of Hell in Dante’s Inferno (Canto 29). The Eighth Circle is actually divided into ten concentric bolgie , or ditches, each one presumably worse than the last. The falsifiers occupy the innermost and presumably worst bolgia . By comparison, the outermost bolgia is for panderers and seducers who are whipped by demons as they march. Used with permission of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum; anonymous loan in honor of Jakob Rosenberg, 63.1979.1.

Here’s a question that lies at the intersection of biology and philosophy: Is itch a unique form of touch sensation that is qualitatively different from the other touch modalities, or is it merely a different pattern of stimulation that relies upon one or more of the touch senses we have already encountered in this book? By analogy, is the relationship between itch and other touch sensations like that between a saxophone and a piano? Each produces sound, but those sounds are qualitatively different. Or is it like the relationship between bebop jazz played on the piano and classical music of the Romantic period played on the piano? They, too, are clearly distinguishable because of their musical structure and context, but they come into being on the same sound-producing device. In the past, this type of question would have been left to philosophers. Today, biology can add to the discussion.

Читать дальше