Unlike the others, he did not beg for leniency. I admired his obstinacy in fighting for what was right. He kept his promises, no matter the consequences.

I’d heard all my life how my grandfather had asked that he be shot on February 16, the most glorious day in the country’s history. On that date in 1918, Lithuania became free of Russia after three centuries of occupation. But intent upon exacting punishment until the last possible moment, the KGB refused Noreika’s patriotic request. Instead, they executed him ten days later, having expressly brought in, from the Urals, a left-handed executioner known for his cold-blooded style. On the day of my grandfather’s execution, the KGB—perhaps seeking to avoid drama—escorted him to the prison basement, asked him to sit at a table, and may even have given him a cup of coffee. When he least suspected it, the executioner crept up behind him and shot him twice in the head.

At the end of the tour of the former KGB prison my mother, brother, and I were met by a thin, elderly man named Rudolfas Jurgis Minajevas, who carried a guitar and sang a ballad that he had composed about my grandfather. It was Ašmenskas who had prepared this delightful surprise. He took us to the window on death row through which my grandfather had answered him all those years ago. There Minajevas sang a ballad that allowed us to visualize my grandfather’s last days.

One cloudy February morning,

Suddenly everyone wakes up.

The Soviet guards are lively again!

The fierce judge

Smiles with calm:

As he sentences Jonas Noreika to death.

Death by bullets is reasonable!

A song erupts in blood.

They stilled our soldier too soon!

The Fatherland is quiet,

Remembering at least for a while

How the dull-witted Soviets tortured him.

The mind doesn’t rest.

Be free, homeland,

As you belong to Holy Mary.

The brother’s blood is pure

And will not dry in our memory!

We will rise passionately and fight. [9] Ašmenskas, Generolas Vėtra .

After his execution, my grandfather’s body was tossed into a pit on the grounds of Tuskulėnai Manor, about five miles away, and covered with limestone. It lay entombed there for more than fifty years, while his spirit both sustained and haunted our family.

Vilnius

October 1, 2018

The petitioner [Grant Gochin] relies on the theories of J. Noreika’s activities based on research conducted by Andrius Jonas Kulikauskas, a lecturer at the Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, Department of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, as well as Evaldas Balčiūnas. They have concluded that:

1. J. Noreika led the criminal gang, the Lithuanian Activist Front in Telšiai, which acted in the name of the Republic of Lithuania, the Lithuanian nation, and the Žemaičių Land. In that capacity, he killed more than 3,000 Jews in one month. He also arrested, humiliated, tortured, and condemned more than 300 Lithuanians.

2. J. Noreika was chosen to serve the Lithuanian Provisional Government and the Nazi occupiers as chairman of the Šiauliai District because he was particularly suited to managing crimes against humanity.

Vilnius Regional Administrative Court File No. el-4215-281/2018 Response from the Genocide Resistance and Research Centre to the prosecution’s claim against the Genocide Centre’s refusal to change its historical conclusion on Jonas Noreika

CHAPTER FOUR

The Last Letter

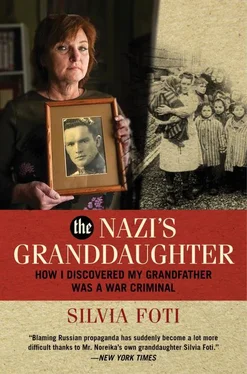

The last communication from my grandfather to my mother was sent from the KGB prison on December 25, 1946, two months before his execution. It was a letter from a loving father to his seven-year-old daughter. In my parents’ home this letter was often read aloud on Christmas Eve. My mother had encased it in a velvet-trimmed frame and hung it in the dining room. It now rested in my office, displayed on top of volumes of Lithuania’s history during World War II, as a librarian might showcase a rare or precious item.

My mother and grandmother had fled Lithuania eighteen months before the date of this letter. They left when the Soviet Union occupied the country for the second time, in July 1944. They were living in Switzerland when the letter arrived. They would not learn for years that my grandfather had died two months after writing it; the Communists did not disclose his death until 1956. The complete lack of information about his fate during those twelve years kindled in my mother and grandmother a mixture of hope and fear that effectively paralyzed them. What should they do? Where should they stay? How would Jonas find them? Their frequent recounting of this situation as I was growing up created a sense in me that time had stopped when my grandfather was taken prisoner, that he would be held interminably, and that I had to get him out.

By 1956, my mother and grandmother had moved to Chicago. My mother met my father at Loyola University. They married in 1960 and welcomed my arrival a year later. In 1964, my brother was born.

The letter of December 25, 1946, was a family treasure, a talisman that my mother would touch when she spoke of her father. One Christmas Eve, perhaps in 1975, our family gathered around the dining room table and squeezed into our places one by one in that small room. Mom set out a plate for my grandfather, a tradition to honor the departed. His plate and his glass of wine remained in place throughout the meal. As always, Mom began with a prayer. “We are gathered here to remember your birth, Jesus Christ, for which we are grateful, and also our relatives who are still suffering under the Communist occupation, as well as those who have passed away, like my father.” The mention of him made her cry. Močiutė squeezed my hand for comfort, as always. But Mom, with her flair for the dramatic, removed the framed Christmas letter from the wall and read it.

Dalia! To my one and only child,

You don’t know cruelty, why birds made of lead reflect the sun’s rays while dropping destructive bombs on large cities. You still don’t know deceit. Your heart is like the white dove on my windowsill. Yet you will mature and comprehend everything, that life is an eternal struggle. Only the strong win. Power rules. But power is two-sided: creative and destructive. Creative power is love, while destructive power is hate. I want to see you strong, firm, and filled with creative power. May God help you, my child of love. [1] Jonas Noreika’s last letter to his daughter (written from the KGB prison).

When she finally hung the letter back in its place, she lifted a silver tray of plotkelės , unconsecrated Communion wafers, and offered one to each of us. Tradition required us to share this wafer with everyone present, wishing each person good health, good luck, good grades in school, good fortune in work, or anything else he or she particularly wanted. When it came to the wafer that she had placed on my grandfather’s plate, we each broke off a piece of it and wished him happiness and success in heaven, or asked for his help in life—as if he’d been beatified.

On other occasions, I asked his help in establishing a writing career, something I had set my heart on by eighth grade. Mom often told me that her father had been a very good writer; he’d worked as a journalist for newspapers and military magazines, had written short stories, even a novel, and had won literary prizes. I would break off a piece of his wafer and chew it slowly, entreating him: Grandfather, you know I’ve already chosen a career in writing. I know it’s not practical. Močiutė wants me to be a lawyer, like you, but I’d rather be a writer, also like you. If you have any influence, please look over my shoulder and help me.

Then we would sit down to eat twelve cold dishes representing Christ’s twelve disciples. These included black bread, potato salad, red beet vinaigrette, a green salad, fried cod, herring with onions, herring with tomatoes, herring with green peppers, herring with carrots, herring with mushrooms in sour cream, poppy-seed milk, and cranberry pudding. As we nibbled and sipped, I would check my grandfather’s glass of wine every few minutes to see if he had drunk any of it. When we weren’t looking, my father would gulp down its contents and set the wine glass back in its place. He then would draw our attention to the evidence that my grandfather had just joined us for dinner. We always laughed. Nonetheless, the presence of our heroic grandfather was made palpable—as was our loss, and the injustice of his absence from our lives.

Читать дальше