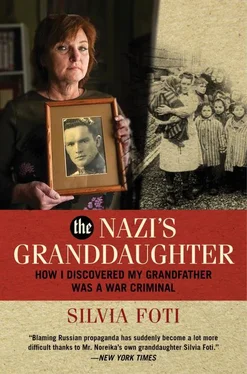

I felt like a princess, growing up as the granddaughter of a hero who had bravely resisted the Communists and been tortured by the KGB. I basked in the warm affection and approval of everyone in Chicago’s Lithuanian community: at song and dance festivals, at summer camps, and at concerts in which my mother sang. I was heir to Jonas Noreika’s illustrious legacy: Jonas Noreika the lionhearted. Growing up with this sense of family distinction, of noble heritage, felt like having a trust fund. The aura of heroism seemed to have been transferred magically to me, to inform my very essence. A diamond tiara couldn’t have made me feel more special.

From one of my bookshelves, I pulled out a biography of my grandfather and studied the cover. It bore a photograph of my grandmother playfully pulling my grandfather toward her by his necktie. The author was Viktoras Ašmenskas—one of my grandfather’s colleagues who, having taken part in the rebellion, was imprisoned with him. I had been reading this volume for a second time. Entitled Generolas V ė tra (General Storm), it was published in 1997 by the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, which runs the Museum of Genocide Victims, the one I had visited with my mother and brother. [4] Ibid.

The museum was created in 1992, shortly after Lithuania’s independence, to demonstrate to the world that, just as Jews had suffered and perished during the Holocaust, Lithuanian nationalists had suffered under Communism during World War II. Many of them had died in Siberia. My grandfather’s name is inscribed along with many others’ on the gray marble walls of the very building in which he was murdered in 1947.

During our 1997 trip to Lithuania, Ašmenskas had told me that death row prisoners were held in isolation chambers in the basement near the coal bin. In February 1947, while an inmate himself, he had gone up to a window there to ask, “Hey, is Noreika there?” A voice replied from the darkness, “Yes, I’m here.” The voice belonged to my grandfather, who smiled as he grasped the metal window bars.

I put down his book, which contained this account, and stared up at the gold-painted image of my grandfather. How could you smile on death row? You were only thirty-six years old! Even when staring death in the face, you did not allow yourself to be overcome by man’s natural terror. You never lost hope that your beloved country would be free. Those traits of his—courage and optimism—I strung like pearls onto the necklace that was my family’s legacy, my inheritance. I aspired to those same qualities; I wanted to be just like him.

In his book, Ašmenskas relates that shortly after he visited my grandfather on death row, the KGB drove my grandfather 176 miles northwest, to Telšiai, to testify against one of the men whom he had recruited to lead the rebellion. The KGB promised my grandfather his freedom in return for a damaging statement against Major Jonas Semaška. [5] Ibid.

My grandfather refused. He stood tall, defying the terrible Communists, and spoke of the Soviet occupation as the genocide of Lithuania. He must have known that such a declaration of loyalty could cost him his life.

Setting Ašmenskas’s book down, I tried to absorb this part of the story into the very fiber of my being to strengthen my perseverance during adversity. I was delighted to claim such an outstanding pedigree.

I returned to my reading, feeling as if I had walked into a time capsule. It was heartening to realize that my mother’s and grandmother’s sacrifices had contributed to Lithuania’s freedom. They’d had to continue their lives without their husband and father, knowing what torment he had endured during his last years. According to Ašmenskas, the KGB had thrown General Storm into an iron tank nicknamed the “Black Raven,” which often was placed in the prison courtyard. Its sealed vertical compartments were like narrow coffins. A prisoner shut up inside one of them was forced to stand for hours. Occasionally prisoners crossing the yard walked past it. If no guard was patrolling, it was possible to have a brief conversation.

One prisoner hollered at the Black Raven, “Who’s in there?”

“Jonas Noreika!”

The other prisoner shouted, “The Moscow Supreme Court agreed to abolish the death penalty! Write an appeal, to buy more time.”

After a short silence, Noreika answered, “No, I won’t write it. I categorically forbid you to write it in my name. My trial was not legal. I am a war prisoner. I followed my soldier’s oath and duty. I have taken the highest responsibility in the war for freedom and will answer only to the National Council. By asking for a pardon, I would recognize the occupier’s authority, thereby negating the authority of Lithuania’s independent government. Let the Council know. Soldiers make decisions according to their conscience and the war’s circumstances.” [6] Ibid.

At the Museum of Genocide Victims my mother, brother, and I stood at the front of an interrogation room in the basement and tried to picture the trial held on November 15, 1946. Jonas Noreika stood before a KGB prison judge, wearing gray prisoner’s garb, his beard long and scruffy, his face and body bruised, his hands manacled. Was the judge wearing a military uniform? Was there a surly portrait of Vozhd (Leader) Joseph Stalin overlooking the proceedings? My grandfather declared himself to be the defense lawyer, representing the eleven men who had formed a rebellion against the Communists. The judge magnanimously agreed to this arrangement. He already knew the trial’s inevitable outcome.

After the trial, my grandfather and a colleague were transferred to a nearby prison to await their execution. A fellow prisoner remembered seeing them in the courtyard near the gate; Ašmenskas described this scene in his book. One of the inmates exclaimed, “Men, look! Above Noreika’s head shines a halo—and there’s one over Zigmas!” [7] Ibid.

I closed the book and patted its cover. This was the best part of the story, I always thought: the two heroes with halos glowing above their heads just before their execution. Surely it was a supernatural sign, signaling that they would be sent straight to heaven as a reward for their martyrdom.

Now, fifty-three years after those events, I perused the transcripts of the KGB trial and was able to read exactly what each man had said before being sentenced. The transcripts had been translated from Russian into Lithuanian, which I then translated into English. At the end of the trial, the eleven defendants gave their closing statements.

Stasys Gorodeckis, second-in-command to my grandfather, stated, “I’m on this bench because I dream of freedom, an independent Lithuania. I was responsible for pulling in human sacrifices. People are treasures and are necessary for the future. Yes, the defender was correct when he said the rest were brought to the bench because of my actions. Please do not sentence them severely. If the trial can focus on my past work, take into account my ‘mistake.’ I will reform.” [8] KGB transcripts, Case #9792.

Gorodeckis was sentenced to ten years in Siberia and lived out the rest of his life with his family. He died a natural death in 2002.

Zigmas Šerkšnas-Laukaitis, groomed as the leader of the rebellion’s death squad, professed, “Yes, I belonged to the partisans, but I also left them. Noreika involved me again with this matter, with organizing the youth, but I did not know they were called the death squad. Please take that into consideration to lessen my sentence.”

Within three months he was executed—along with my grandfather.

All of the other prisoners’ statements paled in comparison with my grandfather’s; he went out in a blaze of glory. When it was his turn to speak, Jonas Noreika valiantly proclaimed, “I was born in Lithuania, prayed for the nation. Life under the Russians was difficult and dark. When I joined the Lithuanian Army I took an oath for freedom of religion, liberty, and independence. Because of my beliefs I joined the war against the Soviet government against the Bolsheviks. All the facts prove in this trial that my colleagues and I wanted an independent Lithuania. I could not just sit on my hands. I tried using all means available, but it did not succeed. I willingly worked for all of this.”

Читать дальше