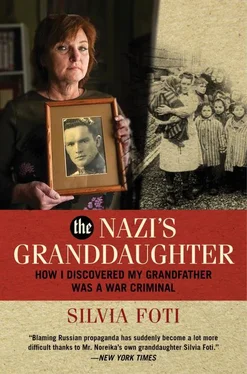

Silvia Foti

THE NAZI’S GRANDDAUGHTER

HOW I DISCOVERED MY GRANDFATHER WAS A WAR CRIMINAL

God once said that when it rains it means He’s crying over somebody. If a country calls itself Land of Rain it means God is crying over everybody.

—Močiutė

Jonas Noreika—General Storm—in his uniform as an officer in the Seventh Grand Duke Butigeidis Regiment of the Lithuanian Army in the 1930s, perhaps on his December 26, 1936, wedding day. Colorized

INTRODUCTION

Long, Long, Long after the Beginning

Chicago 2019

My grandmother confessed that she fell in love with him because he looked like a Hollywood movie star—a swashbuckler battling the evil Communists who had subjugated and ravaged our tiny, proud country.

Over the years, she sang only his praises.

The details of his life that she crooned as I grew older only enhanced his image in my astounded eyes. He had been interrogated and beaten with a baton for two years in a crowded KGB prison. He had led a revolt against the Russians—not once, but twice. He had dared to clash with the mighty Germans, and for his impertinent insolence been sent to a concentration camp where the Nazis pounded him with their fists.

That story is all I knew for thirty-eight years. I had no hint of anything deranged about him.

So I was caught so implausibly uninformed that the shameful evidence flattened me. I had known nothing about his machinations in the genocide, nothing about his prowess in organizing the redistribution of the property of those marked for death with a yellow star, nothing about the sinister orders he signed to squash thousands of innocent civilians into a cheek-to-jowl-packed ghetto in advance of certain execution.

Apparently, and more surprisingly, neither did anyone else.

Or if they did know, they feigned ignorance. State-sanctioned ignorance, in my parents’ homeland of Lithuania, where people wish I had done the same. My frank disclosure of my grandfather’s deeds in a July 2018 Salon article—which led to front-page news stories in the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune —prompted not only cries of vindicated triumph from those who had been traumatized by the Holocaust, but also a clamor of outrage from Lithuanian patriots, who convinced themselves I must be a KGB agent working for Russia.

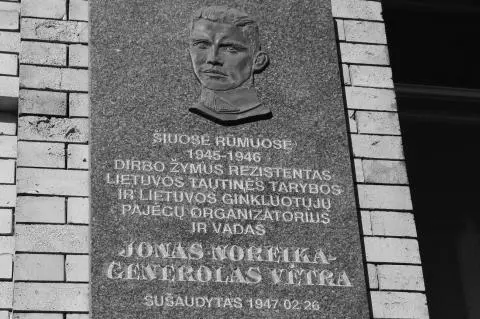

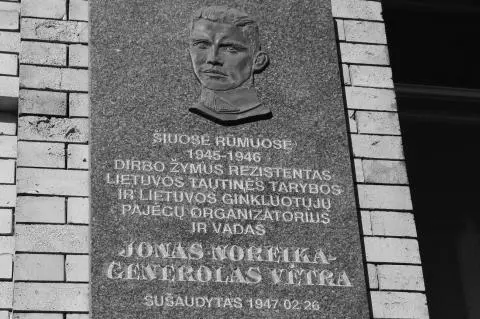

The Wroblewski Library in Vilnius, the site of the controversial plaque celebrating Jonas Noreika

The ensuing media explosion in Eastern Europe stirred an aspiring European Union Parliament candidate to swing a sledgehammer fourteen times against a bronze plaque commemorating my grandfather and to scatter its pieces all over the capital city of Vilnius.

Plaque attacks ensued. The local mayor glued my grandfather’s plaque back together and defiantly displayed it again. Then, in an impressive political pirouette, he acquired a case of plaque remorse and impulsively removed the memorial in the middle of the night. The mayor’s anti-plaque reaction cued an incensed mob of patriots to pimp the plaque with a complete makeover and rehang it in broad daylight to the accompaniment of rousing folk music.

The original plaque honoring my grandfather, mounted on the exterior of the Wroblewski Library in 2000. It reads: “In This Building from 1945–1946 Worked a Noteworthy Resistor Lithuania’s National Council and Lithuania’s Armed Forces Organizer and Leader Jonas Noreika General Storm Shot February 26, 1947.”

The new and improved plaque, hung in 2019. It reads: “In This Building from 1945–1946 Worked a Noteworthy Resistor, Stutthof Concentration Camp Prisoner, Lithuania’s National Council and Lithuania’s Armed Forces Organizer and Leader Jonas Noreika General Storm Shot February 26, 1947.”

Plaque up: 3. Plaque down: 2.

It was flamboyant political opera.

Imagine Christopher Columbus’s granddaughter revealing evidence that he had murdered indigenous peoples, publishing an article about his atrocities, calling for the removal of all his honors including the beloved national holiday, and causing a national scandal of daily press stories and protests in the United States. That is the equivalent of what has been happening in faraway Lithuania, where the real history of World War II has ambushed the newly nascent democracy with a vengeance.

My grandfather’s plaque and the patriots who celebrate him may have polarized the Land of Rain like a Klan rally around a Confederate statue. But everybody can agree on at least one thing about him. My grandfather really did look like a Hollywood movie star.

Not Nearly as Long after the Beginning

Chicago 1960s

The sacred Lithuanian warrior Vytis, depicted on our little country’s coat of arms, occupied a big place of honor in our dining room. My mother had placed it there to ensure that his proud image would exert a constant influence upon our minds, if not upon our dinner table conversation. As a young girl, I gazed upon this white knight in full armor against a crimson ground and pondered the mystery of Vytis. He held his sword high, as if commanding me in his booming voice to love the old country forever, to never forget it, and always, always to fight for freedom.

My mother and grandmother had taught me all the magnificent legends of Vytis. His very name meant “the one who chases out our enemies.” When I cried because I was scared of him, they shushed me. I didn’t like hearing about how Vytis had hunted our encroachers in a bloody battle, killing and killing and killing. Nonetheless he entranced me, and I wanted to know everything about him: How he was thrown from his horse when our country fell under Russian, German, and Polish rule. (It remained subjugated for three hundred years.) And how on February 16, 1918—the most glorious day of our history—Vytis mounted his steed once again and led Lithuania to independence. My grandparents met and my parents were born during the twenty-two glorious years of liberty that followed.

Oh, how Vytis bewitched me! He conjured so many deep and mysterious feelings toward our hallowed homeland. Vee-TISS! I cried in agony about the Soviet Union’s annexation of our land in June 1940. Vee-TISS! Vee-TISS! I wailed in horror at the story of the German invasion in 1941. I threw a tantrum of indignation when told how the Red Army reoccupied Lithuania and vanquished Vytis in 1944.

My mother and grandmother seemed like priestesses summoning Vytis as a lord luxuriating in a bloodbath as they wept over his gory sacrifice. I was horrified. And fascinated.

Читать дальше