I was returning to the living room with our three coffees when I saw Ray stand up, looking like he was going to lunge at our father.

“There’s no way I’ll let you do that!” he shouted. “Mom’s going to be cremated because that’s what she wanted. I’ll make sure of that. Do you understand?”

Dad—whom we called Tėtė—looked bewildered, like an overwhelmed little boy, then nodded and started to weep.

As Ray sat back down, he and I exchanged a look of relief. We were used to fighting about Mom’s wishes with Tėtė. I handed out the mugs, and we busied ourselves with our coffee for a few moments. My chair was next to a small round table draped in a colorful shawl with a black fringe. The table held a Spanish-style lamp whose base was painted with swirls of gold-leafed flowers. Beside it, Mom had positioned a flamenco doll swishing her red dress. I hardly had any room to put down my cup of coffee.

“And the burial?” Tėtė asked.

“She wanted to be buried in Lithuania next to her father,” I replied.

“It was always about her father,” Tėtė said. “He’s all she ever thought about.”

“I know,” I sighed.

“Maybe it’s best that way,” Tėtė said. “You know, we were talking about a divorce, at the end.”

Ray and I exchanged glances. “We know,” we said together.

We decided to have the wake and the funeral Mass in Chicago within the next few days, then to have the funeral home keep our mother’s urn until we could go to Lithuania to bury her cremains.

“I’ve prepared the notice for the newspaper,” Tėtė said, pulling out a slip of paper from his shirt pocket.

“When did you manage to write that?” I asked, bewildered, picturing him grieving yet dutifully hammering out the obituary at the typewriter keys after visiting Mom at the hospital.

“Last night. This morning I typed it.” He proceeded to read it to us:

Dalia Maria Kucenas died February 4, 2000, at 3 am at the age of 60. She lived in the Marquette Park neighborhood of Chicago. She was born in Kaunas.

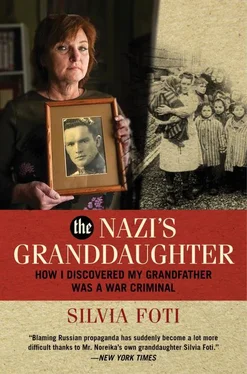

She is survived by her mother, Antanina Noreika; her husband, John Kucenas; her daughter, Silvia Foti; son-in law, Franco; son, Ray; daughter-in-law, Lori; grandchildren, Alessandra and Gabriel Foti, Andrew Kucenas; also her godmother and aunt, Antanina Misiun.

Dalia was the daughter of Jonas Noreika, aka General Storm, a partisan leader.

Dalia was a long-time soloist singer, and she participated in several Lithuanian theater productions. She was the Lithuanian Community’s Cultural Council president and Korp! Giedra president. She was a member of the Lithuanian Foundation and other Lithuanian organizations. She received her PhD in Literature at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

The wake is Sunday, February 6, from 3 pm to 8 pm at Marquette Park Funeral Home. The farewell greetings are at 6:30 pm.

On Monday at 10 am, she will be in a funeral procession to Nativity BVM Church, and at 10:30 there will be a Mass for her soul. She will be buried in Lithuania. Please give your donations to the Lithuanian Foundation.

Welling up with emotion, I walked to the back of the house to the piano room, where my mother used to practice before performances. She had hung photographs of herself as Carmen, as Norma, and as Mimi from La Boheme . I would never hear her beautiful voice again. A primal howl rose up from the core of my being. I was so alone, so alone, without Mom. Even at thirty-eight years old, I felt like an orphaned child.

Shortly after her death, I returned to my old bedroom. Next to the piano room, it had become a repository of all Mom’s research for her intended book. That project—writing my grandfather’s story—had become for me a tangible connection to her, a means of bringing her back from the dead, a way for me to apologize for not having been with her at the moment of her death as I should have been.

In many ways, my old bedroom looked the same—the brick wall still a shiny fire-engine red, the wooden panels still gold and white, the floor still a little slanted down to the east. I looked out the window into my old backyard. Everything seemed so small, including my tiny childhood bedroom, where I had used a space heater to keep warm in the winter and a fan to keep cool in the summer, where I had written in a diary I named “Chris,” where I had propped a pillow next to the wall and rocked myself back and forth, where I had sometimes cried myself to sleep.

My mother’s research, memorabilia, and iconography filled three tall bookshelves. I pulled apart this shrine to her father, hauling it to my house piece by piece. Through all of that task her spirit was palpable. She appeared to me just as I wished, wearing her black stretch pants and her long-sleeved black turtleneck, her hands on her hips, tapping her right foot on the floor. She hovered as I sat there in my old bedroom and wondered where to start, looking around the room, engulfed by paper, books, letters, and folders about my grandfather. Both he and she continued to exert a presence.

The Cross of the Vytis, Lithuania’s coat of arms, was displayed prominently—in the center of the largest bookshelf, which had been arranged like an altar. Mom had received this medal, the highest Lithuanian honor anyone could receive posthumously, from President Algirdas Brazauskas in 1997, for her father fifty years after his execution. I reached for it and held it in my palm, feeling the ribbon and the heft of the bronze medallion, almost sensing it pulse.

Next to the Cross of the Vytis, Mom had set the Order of the Great Duke Gediminas, given to her for her tremendous service to the country. She had volunteered tirelessly—given fundraising concerts, written to newspapers, mentored younger artists—all for her devotion to freedom. On the top shelf, she kept her father’s prayer book, the one he had used in the KGB prison. I sniffed its musty pages. So fragile, like a sick bird, it seemed about to crumble.

I felt overwhelmed with responsibility. Worse, my faith was rattled. I didn’t understand God. He had allowed my grandfather to be executed by the Communists. He’d permitted Mom to die before she could fulfill her yearning to write her father’s story. And he’d left this towering task to me.

I sorted through the jumble of relics and began to sift through the mass of documents: three thousand pages of transcripts from the KGB prison where my grandfather had been tortured and executed, seventy-seven letters written to my grandmother from a Nazi concentration camp, a fairy tale he’d penned for my mother when she was a young child, letters from relatives describing him, hundreds of newspaper clippings lauding his heroics, and nearly twenty photograph albums. Yet there was clearly so much more that I still needed to research.

I spoke to Mom in my mind and believed I could smell her floral perfume lingering in the air, caught at the back of my throat. Mom, it’s going to take a miracle to get this work done. Where am I supposed to start? Silence. Maybe I was praying too. I felt like I was drowning in cement boots.

I could conjure her so easily because her presence clung to me like a silk scarf alive with electrostatic sparks. Her shadow standing in front of me seemed to whisper, Then finish what I could not. Remember: you promised!

The sheer volume of the material she had amassed made the challenge seem all but insurmountable. I knew almost nothing about Jonas Noreika. It was my mother who had known him. She was the one who was supposed to have written the book. Everything was secondhand to me, merely stories I’d been told of how he died a martyr in a KGB prison for leading a rebellion against the Communists. He had died fourteen years before I was born. Who exactly had my grandfather been?

Читать дальше