Vilnius

October 1, 2018

In the file under review, the case originated over a dispute between the petitioner’s [Grant Gochin’s] and the [Genocide] Centre’s assessment of J. Noreika’s (General Storm’s) activities in Nazi-occupied Lithuania. The petitioner demands that the Centre officially recognize that J. Noreika was directly responsible for the deaths of 1,800 Jews in Plungė and 800 Jews in Telšiai (which occurred July 12–13, 1941, and July 20–21, 1941). The Centre, however, has based its assessment on existing historical sources, and has therefore concluded that J. Noreika was not involved in the Jewish mass destruction operations in the counties of Telšiai or Šiauliai.

Vilnius Regional Administrative Court File No. el-4215-281/2018 Response from the Genocide Resistance and Research Centre to the prosecution’s claim against the Genocide Centre’s refusal to change its historical conclusion on Jonas Noreika

CHAPTER THREE

The Imprisonment and Trial of Jonas Noreika

I, Jonas Noreika, son of Baltrus, born 1910 in the village of Šukioniai, Pasvalio district, Šiauliai region, Lithuanian SSR, living in Vilnius on Vivulskio street, number 31, not a party-member, finished high law studies, worked in the bourgeoisie Lithuanian Army from 1935–1940, wife Antanina Noreika, born 1911, with daughter living in Germany, in the British-occupied zone, not tried, imprisoned, was from March 16, 1946, declared guilty. I request to represent this group as their lawyer. No, I demand it!

—KGB Transcripts, 1946

[1] Jonas Noreika interrogation, Case #9792, KGB transcripts, March 16, 1946–February 1947, Lithuanian Special Archives, vol. 1, pp. 304–6, translated from Russian to Lithuanian by Damijonas Riauka in 1997 and from Lithuanian to English by the author.

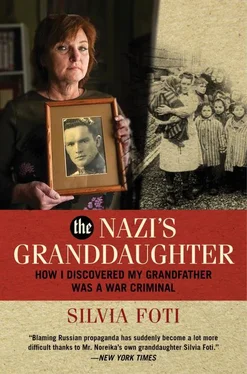

Afew months after Mom’s death I hunkered in my home office, looking vacantly at a keyboard, trying to find the motivation to assemble the words. My grandfather. On my right towered three bookshelves packed with yellowing documents my mother had collected over forty years about her renowned father. He died two score and thirteen years ago. As a spring breeze blew in through my white curtains, I resolved to cast the story as a traditional biography, a third-person account that would include a sprinkling of secondhand memories and anecdotes told by my mother and grandmother. These might prove useful as footnotes for historians. Larger-than-life legend . The gold-sprayed bust of Jonas Noreika that I had lugged from my mother’s studio now hung over my desk, his eyes glaring down at me. Don’t embarrass the fatherland.

Growing up in Chicago’s Marquette Park neighborhood, which boasted the largest population of Lithuanians outside the homeland, I had heard how at the age of thirty-six my grandfather had died at the hands of the KGB, a martyr for Lithuania’s freedom. According to my family’s account, he led an uprising against the Communists and won our country back from them, only to have it snatched by the Germans. He became district chief of the northwestern part of the country during the German occupation. Apparently, he fought the Nazis, who then sent him to a concentration camp. He escaped from that camp and returned to Vilnius, planning to start a new rebellion against the Communists—but was caught, taken to a KGB prison, and tortured. [2] “Jonas Noreika,” in Lietuvių Enciklopedija 20 (Boston: Lithuanian Encyclopedia Press, 1960).

I recalled my last visit to Lithuania, three years earlier—in 1997—when my mother, brother and I had visited the Museum of Genocide Victims, the former KGB prison where Jonas Noreika’s trial had taken place. My mother was on a concert tour and also conducting research for her book project, reconstructing the torture and trial so that she could chronicle the life of her celebrated father. He had been prosecuted with ten other rebels and then executed.

Inspired by my mother’s keen interest, I was writing a long article about my grandfather for Chicago’s Southtown Economist. It was published on April 18, 1997.

At the Museum of Genocide Victims, we were led to the basement to see the prison cells and interrogation rooms. My grandfather had stood for hours, waiting for his paperwork to be processed, in one of those two dark cells, the size of coffins, called “boxes.” He was then dragged to a fifteen-by-ten-foot lime-green cell crammed with forty traitors. In the corner squatted a plastic pot (called a parasha ) that served as a toilet. Lights glared round the clock. The whole system was designed to prevent sleep, to keep these bourgeois traitors from escaping this proletariat hell. That’s why they conducted interrogations at night: to rob alleged conspirators of sleep and sanity. Prisoners were forced to stay awake from seven in the morning to ten at night and could be sent to solitary confinement if caught napping. My grandfather had dozed off after a long night of questionings and beatings; for that, he was sent to solitary confinement. [3] Viktoras Ašmenskas, Generolas Vėtra (Vilnius: Lietuvos Gyventojų Genocido ir Rezistencijos Tyrimo Centras [Lithuanian Genocide and Resistance Research Centre], 1997).

Our guide showed us a series of chambers in which prisoners had endured torture inflicted for any of a number of reasons: falling asleep during the day, failing to confess, or tapping out a Morse-code message to a fellow prisoner in an adjoining cell. We viewed a “cold chamber,” which looked like a large freezer with a thick refrigerator door. A KGB guard would have opened that door and forced a naked prisoner to crouch down on all fours to enter it. Our guide invited me to crawl into the refrigerator for the sake of my newspaper article, but I merely poked my head into the dark, musty interior. We were told that the prisoners who emerged from its confines usually contracted pneumonia.

Another torture room was apparently part of every prisoner’s life. In the “water chamber” a tiny platform stood in the center of a small room filled with a foot of icy water. Prisoners were forced to stand at attention on the platform in their underwear. After hours of standing, they inevitably weakened and collapsed from fatigue into the water. Then they were made to stand in the frigid water until their knees buckled, after which they were beaten for their lapse. The punishment was circular, inescapable.

Down another hallway, we were directed to the “rubber chamber,” a padded cubicle intended to muffle the cries of prisoners who had gone insane. Those who turned raving mad were wrapped in black straitjackets, some of which were displayed in a window, their extra-long sleeves and ties a testimony to the fact that ceaseless brutalizing of the body often leads to the unraveling of the mind—perhaps the worst agony of all.

The “death chamber” was where prisoners were shot in the back as they sat at a table in a kitchenette, unaware that they were about to be killed. That’s how my grandfather was executed, the tour guide explained. We peered at an old, green wooden table and chair. I pictured my grandfather in that chair, drinking a cup of coffee, the guard sneaking up behind him and shooting him twice, my grandfather’s body slumping over the table, his coffee spilling onto the floor.

My grandfather’s nom de guerre was General Storm. A leader of the underground resistance movement, he was recognized as a hero and a martyr to the cause. I thought of all this as very romantic. These were my psychosocial genetics: this glorious history whose telling always began with my grandfather’s death, whether I was sitting on my grandmother’s lap, in Lithuanian school in Chicago on Saturday mornings, or in conversations with anyone who had known him.

Читать дальше