It was not easy to live with the constant shadow of his memory. We commemorated his birthday, October 8. We also marked the date on which he had requested to be executed (even though the Communists killed him on February 26). Their cynical and callous attempt to consign Jonas Noreika to oblivion served, as intended, to sharpen our grief.

This perpetual sense of bereavement, this shroud of grief, caused division in our family. As Mom and Močiutė groomed me and Ray to identify with our courageous ancestor, my father often must have felt like an outsider. Dad almost certainly resented the fact that he never seemed to measure up against his phantom father-in-law. “Your mother’s father was a general; mine was a janitor,” he remarked.

Every room in the house declared that our family was Lithuanian—forced by the Communists to live, against our will, in another country. We often acted as if we comprised a country unto ourselves here—as if the backdrop of a free America were purely incidental, of little consequence to us. Our true goal was to obtain freedom for Lithuania.

“Someday, Lithuania will be free,” Mom told us. “It’s up to us to help save the country from the Communists. My father died fighting for our country’s freedom, and we must do everything we can to live up to his honor.”

On Saturdays Ray and I attended Lithuanian school, where we’d have to write essays about how we could help the fatherland achieve its freedom. In one essay, written when I was about eight years old, I asserted, “I have to get a good education and get involved with the American government to convince this country’s leaders to save the Baltic country. They’ll send American soldiers to Lithuania to kill the Communist monsters.”

When I showed the essay to my mother, she beamed and read it over the phone to my grandmother, who (I was told) also glowed with pride. Then I showed it to my father. He smiled blandly, saying, “That’s good, Silvia,” and went back to reading the Lithuanian daily newspaper Draugas (Friend).

“Don’t bother your father now,” Mom said. “He’s busy.” She noticed my frown. “Why are you crying? You should feel lucky you even have a father. The last time I saw mine, I was four years old.”

She went into the piano room that housed the Lithuanian encyclopedia set, pulled out the volume labelled N , and opened it to the entry “Jonas Noreika.” In forty lines, it provided a thumbnail sketch of the man whom she constantly compared to Dad.

“Do you see?” she said. “Your grandfather was a hero. He died for his country. That’s why I grew up without a father. You need to feel grateful that you have a father.”

I looked at Dad. He shrugged and walked into his basement office, saying, “I need to work on Lituanus .” He was the publication’s volunteer business administrator by night; by day he worked for Chicago City Hall as a bookkeeper in the comptroller’s office. “I have two jobs,” he liked to say.

Mom saw my crushed expression. “Your father’s very busy, that’s all. He goes to work during the day to pay our bills. At night, he works for the Lithuanian cause, just like my father used to. You understand, don’t you?”

“I suppose so,” I mumbled.

Dad was a quiet man who managed to stay out of everyone’s way. Because he seemed emotionally distant, my mother invoked the spirit of her father as the other adult male role model for Ray and me. Her father’s sentences, encased in red velvet, hung with his photograph next to the Vytis.

I envied my mother for having had a father who could write her a letter like that. Although I had never met my grandfather, I’d learned to love him the way a daughter loved a father.

All exiles have their private griefs. My family’s tragedy, I thought, was grander, more epic than most.

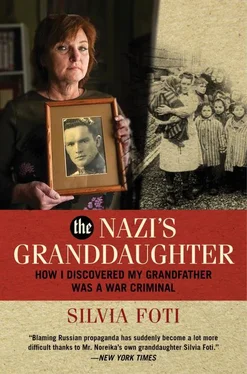

My grandfather’s legend and my promise to my mother obliged and encouraged me to write. While raising my son, then three years old, and my daughter, aged seven, I ran a freelance writing business. Neither my young children nor my husband of fourteen years could understand my obsession with my grandfather. I seemed to spend more time with his ghost than with them. They, too, felt the sacrifice of his martyrdom; it was a multi-generational cost.

Vilnius

October 1, 2018

The petitioner [Grant Gochin] claims that J. Noreika was one of the most prominent antisemites in Lithuania who desired and relished the idea of killing Jews, who drew others into killing Jews, who justified their actions, and who personally ordered the shooting of Jews in Plungė. The petitioner requests that the [Genocide] Centre accept his version.

Vilnius Regional Administrative Court File No. el-4215-281/2018 Response from the Genocide Resistance and Research Centre to the prosecution’s claim against the Genocide Centre’s refusal to change its historical conclusion on Jonas Noreika

CHAPTER FIVE

The Blue Danube

Five months after my mother’s death, my grandmother was again critically ill. I faced another unfulfilled promise: I had not yet learned to play “The Blue Danube” waltz on the piano that Močiutė had bought for me ten years earlier. Her gift had been accompanied with that one request: “Please learn how to play ‘The Blue Danube.’ I want to remember my wedding day, the happiest day of my life.” Even her gift to me was a means of paying tribute to my grandfather.

I estimated that it would take a few weeks to learn to play the waltz to Močiutė’s satisfaction. She hated mistakes.

I got a copy of the score, set it on the brown upright piano, and tentatively began to practice. I had taken lessons for eleven years as a child and occasionally accompanied my mother as she sang, but it had been at least a decade since I had played the piano. And “The Blue Danube” is a difficult piece, with four-note chords that require spanning an octave with one hand. My fingers were slow at first, but I gradually gained confidence—first with the right hand, then with the left, then with both together. But everything sounded sour. I needed to call a piano tuner.

“You haven’t tuned your piano in ten years?” he asked incredulously.

“I barely touched it,” I said, defensive.

“It’s a crime to ignore a piano for this long.”

“I know. Can you hurry?”

As I continued to practice in those early days of summer 2000, nothing seemed to be in harmony. How could I possibly fulfill my promises? How could I go on without Mom or Močiutė? I spent hours going over the notes of my grandmother’s wedding song, until I felt the patriotic music in my bones and heard the rustle of long dresses swirling around a glittering ballroom.

I became so accustomed to playing the song that my mind wandered as I stroked the keys. Everything from my mother and grandmother had always come with a condition. And those conditions had framed my entire life. My grandmother’s gift of a piano had come with the condition that I learn to play a complicated waltz reminiscent of the Noreika mythology; I learned the piece because she expected it of me. My mother had claimed on her deathbed that she wouldn’t die in peace unless I agreed to write a book about her hero. Because I wanted their love and approval, I agreed to all their demands: do everything you can to help Lithuania by learning the language, understanding the country’s complex history, and passing down to your children the stories of our heritage. I didn’t question these requirements, but I had delayed acting upon them.

Wanting to let my grandmother know that I was working to fulfill my promise and practicing “The Blue Danube,” I visited her at her apartment a few blocks from my home. I sat on her bed while her caretaker Nijolė clanged pans in the kitchen, preparing dinner.

Читать дальше