“How should I respond?” Tėtė asked quietly.

“That’s up to you,” I said.

He shook his head. “I don’t think she wanted me next to her. Did she ever mention that to you?”

My heart sank for him. “No. She only mentioned that she wanted to be buried next to her father.”

“You know, this is the first time I’m beginning to realize how strange our marriage was.”

In the ensuing months, Ray coordinated the DNA analysis with Rimas Jankauskas, a scientist at the University of Vilnius who had been involved in the excavation of my grandfather’s bones in 1994.

My grandfather was one of many Lithuanians executed by the KGB and buried in the park of Tuskulėnai Manor. “The place was convenient: It was strictly guarded and not far from downtown, where the KGB was headquartered. KGB officials were afraid of guerrilla activities in the outskirts of Vilnius,” wrote Dr. Jankauskas in a personal letter to my brother.

Nearly one thousand bodies were buried in that park between 1944 and 1947. Fifty years later, on July 4, 1994, exhumations by a team of archeologists and anthropologists began. Seeking to identify Jonas Noreika’s remains, Dr. Jankauskas had narrowed down the possibilities to two skeletons, numbers 550 and 551, both found in hole number 29. Now he sent samples of their thigh bones, along with the hair and blood samples that my mother had provided, to a company in Canada that my brother had chosen for DNA analysis. After several attempts, that company responded with the same result that the Lithuanian government’s inquiry had yielded years earlier: because the bones had been buried in limestone for so long, it was impossible to identify the DNA.

We would bury our mother and grandmother at the gravesite earmarked by the government for our grandfather, but his remains would not join theirs.

Weeks before our trip to Lithuania, my father had a heart attack—his second—and decided to stay home under the care of his new wife, Nijolė. She had been my grandmother’s caretaker during the five months from my mother’s death until my grandmother died.

My brother and I would make the emotional pilgrimage by ourselves.

PART II

A TROUBLING RUMOR

The sad, quiet duties that fall to families as they prepare their dead for burial were unexpectedly lent an official, ceremonious air. Ray and I arrived in Vilnius on a cool, overcast day in early October that smelled of rain. We were the last passengers to disembark after the long flight. We slowly descended the steep steps onto the tarmac, carrying in thick cardboard boxes the funerary urns that we had taken as carry-on luggage. Ray held Mom’s ashes, while I clutched Močiutė’s. They were heavy—about twenty pounds each—and I was afraid I would lose my balance. Gripping the handrail to steady myself, I caught Ray’s eye. He gave me a reassuring smile. Our relationship had deepened with the one-two loss of our mother and grandmother, followed by our father’s swift remarriage.

About fifteen relatives and a few friends awaited us at the foot of the stairs, each with a dewy flower and a dry kiss. I failed to recognize many of them. Most, I assumed, were relatives of my grandparents, since my mother had been an only child. Others were colleagues of my grandfather. All were dressed in somber gray coats. A black hearse idled behind them.

I knew that many of those here had written letters to my mother. We had met briefly on previous trips, but they addressed me as if we had known each other for years. Bewildered, I tried to remember from conversations I’d had with Mom exactly who was who. My grandfather’s nephew Stasys Grunskis, whose hair was as wild as Einstein’s, shook my hand vigorously. My mother’s friend Zita Kelmickaitė, who had choreographed everything for our arrival, was a celebrity in Lithuania. She was short, with an intense gaze and an electrifying smile. She directed everyone as if we were on a movie set, ordering the videographer, photographer, and journalist to follow us, instructing our relatives to surround us for the photo ops, and continually whispering to an attendant. All the while she kept telling us how happy she was to see us, how much our mother meant to her, and how proud she was of all that our grandfather had done for our country. Her boundless energy buoyed us during this distressing moment. One could see why she would soon be hosting her own morning TV show.

When I had contacted Zita to tell her that my mother and grandmother had died and that I didn’t know how to fulfill their shared wish to be buried in their homeland, she’d said simply, “I’ll help you.”

An attendant dressed in black took the urns from us and placed them in the hearse. After holding them on our laps during the long flight from Chicago, it felt strange to be relieved of this sacred duty. You’re finally here, Mom and Močiutė!

The attendant arranged long-stemmed white lilies and ferns artfully around the urns as the photographer snapped pictures and the videographer recorded. I turned to survey the small airport, my head flooding with thoughts. Now that my mother’s and grandmother’s burials in Vilnius were imminent, I felt that I was being further separated from them—by this place with its bloody history that so fiercely called them home.

Ray and I sat in the back of a relative’s car following the hearse through the city streets, many of them narrow and cobblestoned. An October wind swept past, carrying gold, green, and red leaves that crackled and somersaulted over each other until a strong gust scattered them.

This was not merely a five-thousand-mile trip from Chicago: it was a sixty-year trek back into our family’s history, a journey to a time when our grandfather was still alive, when our mother’s side of the family was still intact, and when the country was being gutted by the Communists and the Nazis. The twenty-two years of independence between the two world wars had been snuffed out. It was a time when Lithuanians were sent to Siberia by the Communists, and Jews were beaten to death by the Nazis or driven out by the truckload to ghettos and then to the woods to be shot.

The wake for my mother and grandmother was held at Vilnius Cathedral. My brother and I stayed at an apartment lent to us by a friend of our mother, and Zita picked us up in a chauffer-driven black limousine. “Everything has been arranged,” she assured us. “Don’t worry about a thing. Of the photographs you gave me, I chose two in which your mother and grandmother look like they’re facing each other. I thought that would be best.”

Ray and I nodded, thanking her again for attending to all the details.

“I placed your mother’s urn on a higher pedestal than your grandmother’s. What do you think about that?”

I smiled. “Even though she was younger, Mom was always in charge of our family, so I think that’s appropriate.”

“Good. That’s what I thought too.”

When we arrived at the cathedral, Zita ushered me and Ray inside, where several hundred guests dressed in black were waiting. More visitors arrived in a steady stream throughout the afternoon. Photographers, videographers, and journalists mingled with the crowd. Zita positioned us at the end of a receiving line in a side area near the urns. My mother’s bronze urn was sculpted in the shape of a lotus flower. Its turquoise color with speckles of gold reminded me of the sea. My grandmother’s yellow marble urn was simpler in style. Both urns stood on white pedestals surrounded by pale lilies and roses.

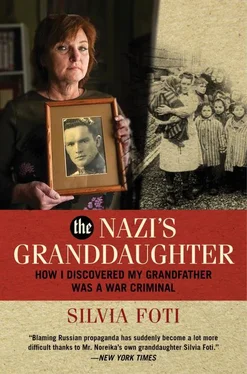

As the guests stood in line to offer their condolences, several I did not recognize asked, “What about the book on your grandfather that your mother was working on? Did she finish it?”

Читать дальше