“How’s the book going?” Močiutė asked.

“Slowly, but I’ll finish it; don’t worry.” I thought this would give her great comfort.

“Don’t write it,” she said flatly, with more energy in her voice than I had heard in months. “Just leave it alone.”

“What do you mean ‘leave it alone’?” This was hardly the response I’d expected.

“It’s best to just let history lie. There’s no need to dig around.”

I assumed that her grief over her daughter’s death a few months earlier had made my grandmother delirious. Perhaps she didn’t want the enormous task that I’d inherited to burden me the way it had my mother. Or maybe, facing her own death, she wanted to free me from my obligation as a parting gift. I searched Močiutė’s face but could not read it.

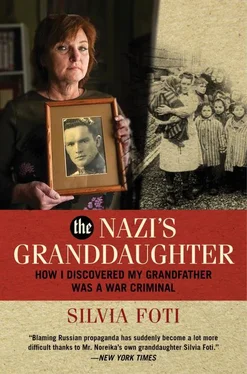

I had been sorting through my mother’s research notes for the past five months, trying to make sense of my grandfather’s life. The Lithuanian community’s expectation that she produce a definitive account must have weighed heavily upon her. Marquette Park was composed chiefly of exiled Lithuanians and their children, all still grieving over the loss of their country and intent upon reclaiming it. Seething over their ancient enemy with a new name—the Communists were now Russians again—our community spoke and acted as if of one mind, like a chorus. It told my mother that a hero like her father could enhance the prestige of their relatively unknown nation on the world stage. Jonas Noreika’s glorious deeds, once publicized, would earn notice and acclaim for the fatherland.

I was still thinking, naively, that it was my mother’s perfectionism that had caused her such mental, emotional, and spiritual stress over the project. I didn’t ask my grandmother why she wanted me to drop the story. It was generous of her to want to spare me an onerous job that might consume my life. Instead, I tried to placate her. “Don’t worry,” I repeated. “I’m young and strong. I have lots of time. Besides, I promised Mom.”

Močiutė shook her head and rolled over in bed to face the wall.

I didn’t take her appeal seriously. Instead, I devoted myself to practicing “The Blue Danube” on the piano again and again. I wanted to keep my promise to her. Maybe I believed it would stop her from dying.

Days later she was rushed to the hospital. Her condition became so critical that the only way I could perform a piano recital for her was over the phone. I implored a nurse to hold the receiver to my grandmother’s ear, while my husband held the receiver on my end. I played with all my heart, pounding the chords, swaying back and forth, finally fulfilling my promise. I pictured Močiutė gliding around the dance floor with my grandfather on their wedding day, setting our family history in motion: my mother’s birth, her father’s disappearance, the emergence of General Storm, my grandmother’s flight from the homeland, and her agonizing longing for it ever since. As I played, I imagined Močiutė transported back to the happiest day of her life.

When I finished, I asked over the phone, “Did you like it?”

“Yes,” she whispered. Nothing more.

I wanted her to praise my effort the way she had cooed over my school essays. I wanted her to recover. But the only sound I heard was her laborious breathing. The nurse informed me that she needed to rest.

The next day, I visited her in the hospital. “How did you like ‘The Blue Danube’?”

“It wasn’t worth it,” she said, looking straight through me.

“What wasn’t worth it?”

“Everything.”

We were interrupted by a Eucharistic minister, who asked her if she would like to take Communion. She waved her hand dismissively.

She seemed like a stranger. She had been going to Mass regularly, cherished the rosary that she carried in her purse, and sang a song to the Virgin Mary every time we drove somewhere on vacation. Now she was refusing Communion?

Confused by her strangeness, I sat on the edge of her bed and held her hand. I was immobilized by an invisible web; we two were the ones left, and soon I would be alone. Whom would I turn to for answers? How was she dealing with the knowledge of what would happen next?

The minister left, shrugging his shoulders.

I couldn’t help but wonder why Močiutė hadn’t taken Communion. I asked her, “Do you believe in God?” I wanted her to still have faith, to believe in heaven so that she’d have solace during her last breath.

She replied, “Christ was just a clever Jew who tricked the world.”

I looked at her as if for the first time. Then I made excuses for her: the contemplation of death must have rattled her mind. I held on to my image of Močiutė on her wedding day, waltzing with her handsome husband, my beloved grandfather, to the popular Viennese tune—one-two-three, one-two-three. I let my heart soar to its legendary cadence.

After my grandmother’s death on July 6, 2000, my father, brother, and I made arrangements to take my mother’s and grandmother’s cremated remains to Vilnius and bury them in the fatherland according to their wishes. Viktoras Ašmenskas, the colleague of my grandfather’s who had written the book about him and was somehow closely connected to the Lithuanian government, had been in touch with us several times before our trip. Three years earlier he had helped my mother to secure a gravesite for my grandfather at Antakalniai, the cemetery in Vilnius where Lithuania’s military heroes and cultural luminaries were buried. He had also helped to coordinate a DNA analysis of the remains, at the government’s expense, to ensure that they were those of Jonas Noreika. Unfortunately, because the bones had been buried in limestone for so long, all genetic markers had deteriorated beyond recognition.

In a phone conversation with Ašmenskas about coordinating my mother’s and my grandmother’s burial arrangements, we asked if he could help to arrange another attempt at a DNA test of our grandfather’s bones, so that we could bury all three family members together. Perhaps forensic technology had improved, we reasoned. He told us that he would contact the Lithuanian government and respond to us in writing.

A few weeks later, we received a letter from Ašmenskas informing us that the government had agreed to analyze our grandfather’s remains but that this time we would have to pay for the investigation ourselves. My father, reading the letter aloud to me and my brother, asked, “Who’s going to pay for this?”

“It was Mom’s wish,” I said. “You have more than enough to pay for it.” He had been bragging about how he’d earned a million dollars on the stock market.

“He wasn’t my father,” Tėtė countered. “Why should I pay for it?”

My brother and I exchanged a glance, a silent conversation passing between us. In fairness, our father had paid the household bills and helped to fund our college educations, but he had never been known for spending beyond the basics. While we were growing up, he frequently lectured us about the importance of saving money. The amount of his savings reflected his self-worth.

“We’ll pay for it,” said Ray.

“Good.” Tėtė resumed reading the letter.

Ašmenskas suggested that we time the burial of our mother and grandmother to coincide with my grandfather’s ninetieth birthday on October 8. We liked the idea. What’s more, it would give us time to hire a DNA-analysis company to confirm the identity of our grandfather’s remains. Ašmenskas asked if we would allow him to speak to the director of the school named after our grandfather. Perhaps the director would invite us to a ceremony to mark the occasion. We agreed.

Ašmenskas’s letter ended by querying my father as to whether he wanted to be buried next to my mother.

Читать дальше