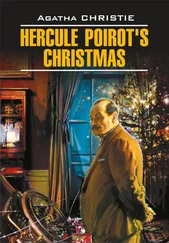

There Rex Donaldson told Theresa at length about his theories and some of his recent experiments. She understood very little but listened in a spellbound manner, thinking to herself:

‘How clever Rex is—and how absolutely adorable!’

Her fiancé paused once and said rather doubtfully:

‘I’m afraid this is dull stuff for you, Theresa.’

‘Darling, it’s too thrilling,’ said Theresa, firmly. ‘Go on. You take some of the blood of the infected rabbit—?’

Presently Theresa said with a sigh:

‘Your work means a terrible lot to you, my sweet.’

‘Naturally,’ said Dr Donaldson.

It did not seem at all natural to Theresa. Very few of her friends did any work at all, and if they did they made extremely heavy weather about it [52] to make heavy weather about smth – находить ч.-л. трудным, утомительным

.

She thought as she had thought once or twice before, how singularly unsuitable it was that she should have fallen in love with Rex Donaldson. Why did these things, these ludicrous and amazing madnesses, happen to one? A profitless question. This had happened to her.

She frowned, wondered at herself. Her crowd had been so gay—so cynical. Love affairs were necessary to life, of course, but why take them seriously? One loved and passed on.

But this feeling of hers for Rex Donaldson was different, it went deeper. She felt instinctively that here there would be no passing on… Her need of him was simple and profound. Everything about him fascinated her. His calmness and detachment, so different from her own hectic, grasping life, the clear, logical coldness of his scientific mind, and something else, imperfectly understood, a secret force in the man masked by his unassuming slightly pedantic manner, but which she nevertheless felt and sensed instinctively.

In Rex Donaldson there was genius—and the fact that his profession was the main preoccupation of his life and that she was only a part—though a necessary part—of existence to him only heightened his attraction for her. She found herself for the first time in her selfish pleasure-loving life content to take second place. The prospect fascinated her. For Rex she would do anything—anything!

‘What a damned nuisance money is,’ she said, petulantly. ‘If only Aunt Emily were to die we could get married at once, and you could come to London and have a laboratory full of test tubes [53] test tube – пробирка

and guinea pigs, and never bother any more about children with mumps and old ladies with livers.’

Donaldson said:

‘There’s no reason why your aunt shouldn’t live for many years to come—if she’s careful.’

Theresa said despondently:

‘I know that…’

In the big double-bedded room with the old-fashioned oak furniture, Dr Tanios said to his wife:

‘I think that I have prepared the ground sufficiently. It is now your turn, my dear.’

He was pouring water from the old-fashioned copper can into the rose-patterned china basin.

Bella Tanios sat in front of the dressing-table wondering why, when she combed her hair as Theresa did, it should not look like Theresa’s!

There was a moment before she replied. Then she said:

‘I don’t think I want—to ask Aunt Emily for money.’

‘It’s not for yourself, Bella, it’s for the sake of the children. Our investments have been so unlucky.’

His back was turned, he did not see the swift glance she gave him—a furtive, shrinking glance.

She said with mild obstinacy:

‘All the same, I think I’d rather not… Aunt Emily is rather difficult. She can be generous but she doesn’t like being asked.’

Drying his hands, Tanios came across from the washstand.

‘Really, Bella, it isn’t like you to be so obstinate. After all, what have we come down here for?’

She murmured:

‘I didn’t—I never meant—it wasn’t to ask for money…’

‘Yet you agreed that the only hope if we are to educate the children properly is for your aunt to come to the rescue.’

Bella Tanios did not answer. She moved uneasily.

But her face bore the mild mulish look that many clever husbands of stupid wives know to their cost [54] to know to one’s cost – знать по горькому опыту

.

She said:

‘Perhaps Aunt Emily herself may suggest—’

‘It is possible, but I’ve seen no signs of it so far.’

Bella said:

‘If we could have brought the children with us. Aunt Emily couldn’t have helped loving Mary. And Edward is so intelligent.’

Tanios said, drily:

‘I don’t think your aunt is a great child lover. It is probably just as well the children aren’t here.’

‘Oh, Jacob, but—’

‘Yes, yes, my dear. I know your feelings. But these desiccated English spinsters—bah, they are not human. We want to do the best we can, do we not, for our Mary and our Edward? To help us a little would involve no hardship to Miss Arundell.’

Mrs Tanios turned, there was a flush in her cheeks.

‘Oh, please, please, Jacob, not this time. I’m sure it would be unwise. I would so very very much rather not.’

Tanios stood close behind her, his arm encircled her shoulders. She trembled a little and then was still—almost rigid.

He said and his voice was still pleasant:

‘All the same [55] All the same – Тем не менее

, Bella, I think—I think you will do what I ask… You usually do, you know—in the end… Yes, I think you will do what I say…’

It was Tuesday afternoon. The side door to the garden was open. Miss Arundell stood on the threshold and threw Bob’s ball the length of the garden path. The terrier rushed after it.

‘Just once more, Bob,’ said Emily Arundell. ‘A good one.’

Once again the ball sped along the ground with Bob racing at full speed in pursuit.

Miss Arundell stooped down, picked up the ball from where Bob laid it at her feet and went into the house, Bob following her closely. She shut the side door, went into the drawing-room, Bob still at her heels [56] at one’s heels – по пятам, следом за к.-л.

, and put the ball away in the drawer.

She glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece. It was halfpast six.

‘A little rest before dinner, I think, Bob.’

She ascended the stairs to her bedroom. Bob accompanied her. Lying on the big chintz-covered [57] chintz-covered – обтянутый ситцем (хлопчатобумажная набивная ткань)

couch with Bob at her feet, Miss Arundell sighed. She was glad that it was Tuesday and that her guests would be going tomorrow. It was not that this weekend had disclosed anything to her that she had not known before. It was more the fact that it had not permitted her to forget her own knowledge.

She said to herself:

‘I’m getting old, I suppose…’ And then, with a little shock of surprise: ‘I am old…’

She lay with her eyes closed for half an hour, then the elderly house-parlourmaid, Ellen, brought hot water and she rose and prepared for dinner.

Dr Donaldson was to dine with them that night. Emily Arundell wished to have an opportunity of studying him at close quarters [58] at close quarters – в непосредственном соприкосновении

. It still seemed to her a little incredible that the exotic Theresa should want to marry this rather stiff and pedantic young man. It also seemed a little odd that this stiff and pedantic young man should want to marry Theresa.

She did not feel as the evening progressed that she was getting to know Dr Donaldson any better. He was very polite, very formal and, to her mind, intensely boring. In her own mind she agreed with Miss Peabody’s judgement. The thought flashed across her brain, ‘Better stuff in our young days.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу