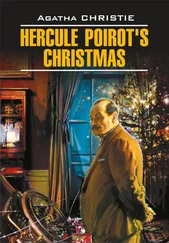

Her mind reverting to her niece’s fiance, Miss Arundell thought, ‘I don’t suppose he’ll ever take to drink [70] to take to drink – стать пьяницей

! Calls himself a man and drank barley water [71] barley water – ячменный отвар (сладкий напиток, приготовленный из ячменного отвара и фруктового сока)

this evening! Barley water! And I opened papa’s special port.’

Charles had done justice [72] to do justice – отдать справедливость

to the port all right. Oh! if only Charles were to be trusted. If only one didn’t know that with him—

Her thoughts broke off… Her mind ranged over the events of the weekend…

Everything seemed vaguely disquieting…

She tried to put worrying thoughts out of her mind.

It was no good.

She raised herself on her elbow and by the light of the night-light that always burned in a little saucer she looked at the time.

One o’clock and she had never felt less like sleep.

She got out of bed and put on her slippers and her warm dressing-gown. She would go downstairs and just check over the weekly books ready for the paying of them the following morning.

Like a shadow she slipped from her room and along the corridor where one small electric bulb was allowed to burn all night.

She came to the head of the stairs, stretched out one hand to the baluster rail and then, unaccountably, she stumbled, tried to recover her balance, failed and went headlong down the stairs.

The sound of her fall, the cry she gave, stirred the sleeping house to wakefulness. Doors opened, lights flashed on.

Miss Lawson popped out of her room at the head of the staircase.

Uttering little cries of distress she pattered down the stairs. One by one the others arrived—Charles, yawning, in a resplendent dressing-gown. Theresa, wrapped in dark silk. Bella in a navy-blue kimono, her hair bristling with [73] to bristle with – изобиловать ч.-л.

combs to ‘set the wave’.

Dazed and confused Emily Arundell lay in a crushed heap. Her shoulder hurt her and her ankle—her whole body was a confused mass of pain. She was conscious of people standing over her, of that fool Minnie Lawson crying and making ineffectual gestures with her hands, of Theresa with a startled look in her dark eyes, of Bella standing with her mouth open looking expectant, of the voice of Charles saying from somewhere—very far away so it seemed—

‘It’s that damned dog’s ball! He must have left it here and she tripped over it. See? Here it is!’

And then she was conscious of authority, putting the others aside, kneeling beside her, touching her with hands that did not fumble but knew.

A feeling of relief swept over her. It would be all right now.

Dr Tanios was saying in firm, reassuring tones:

‘No, it’s all right. No bones broken… Just badly shaken and bruised—and of course she’s had a bad shock. But she’s been very lucky that it’s no worse.’

Then he cleared the others off a little and picked her up quite easily and carried her up to her bedroom, where he had held her wrist for a minute, counting, then nodded his head, sent Minnie (who was still crying and being generally a nuisance) out of the room to fetch brandy and to heat water for a hot bottle.

Confused, shaken, and racked with pain, she felt acutely grateful to Jacob Tanios in that moment. The relief of feeling oneself in capable hands. He gave you just that feeling of assurance—of confidence—that a doctor ought to give.

There was something—something she couldn’t quite get hold of—something vaguely disquieting—but she wouldn’t think of it now. She would drink this and go to sleep as they told her.

But surely there was something missing—someone.

Oh well, she wouldn’t think… Her shoulder hurt her— She drank down what she was given.

She heard Dr Tanios say—and in what a comfortable assured voice—‘She’ll be all right, now.’

She closed her eyes.

She awoke to a sound that she knew—a soft, muffled bark.

She was wide awake in a minute.

Bob—naughty Bob! He was barking outside the front door—his own particular ‘out all night very ashamed of himself’ bark, pitched in a subdued key but repeated hopefully.

Miss Arundell strained her ears. Ah, yes, that was all right. She could hear Minnie going down to let him in. She heard the creak of the opening front door, a confused low murmur—Minnie’s futile reproaches—‘Oh, you naughty little doggie—a very naughty little Bobsie—’ She heard the pantry door open. Bob’s bed was under the pantry table.

And at that moment Emily realized what it was she had subconsciously missed at the moment of her accident. It was Bob. All that commotion—her fall, people running—normally Bob would have responded by a crescendo of barking from inside the pantry.

So that was what had been worrying her at the back of her mind. But it was explained now—Bob, when he had been let out last night, had shamelessly and deliberately gone off on pleasure bent [74] on pleasure bent – жаждущий наслаждаться жизнью

. From time to time he had these lapses from virtue [75] lapse from virtue – грехопадение

—though his apologies afterwards were always all that could be desired.

So that was all right. But was it? What else was there worrying her, nagging at the back of her head? Her accident—something to do with her accident.

Ah, yes, somebody had said—Charles—that she had slipped on Bob’s ball which he had left on the top of the stairs…

The ball had been there—he had held it up in his hand…

Emily Arundell’s head ached. Her shoulder throbbed. Her bruised body suffered…

But in the midst of her suffering her mind was clear and lucid. She was no longer confused by shock. Her memory was perfectly clear.

She went over in her mind all the events from six o’clock yesterday evening… She retraced every step.. .till she came to the moment when she arrived at the stairhead and started to descend the stairs…

A thrill of incredulous horror shot through her…

Surely—surely, she must be mistaken… One often had queer fancies after an event had happened. She tried— earnestly she tried—to recall the slippery roundness of Bob’s ball under her foot…

But she could recall nothing of the kind [76] nothing of the kind – ничего подобного

.

Instead—

‘Sheer nerves,’ said Emily Arundell. ‘Ridiculous fancies.’

But her sensible, shrewd, Victorian mind would not admit that for a moment. There was no foolish optimism about the Victorians. They could believe the worst with the utmost ease.

Emily Arundell believed the worst.

CHAPTER 4. Miss Arundell Writes a Letter

It was Friday.

The relations had left.

They left on the Wednesday as originally planned. One and all [77] One and all – Все без исключения

, they had offered to stay on. One and all they had been steadfastly refused. Miss Arundell explained that she preferred to be ‘quite quiet’.

During the two days that had elapsed since their departure, Emily Arundell had been alarmingly meditative. Often she did not hear what Minnie Lawson said to her. She would stare at her and curtly order her to begin all over again.

‘It’s the shock, poor dear,’ said Miss Lawson.

And she added with the kind of gloomy relish in disaster which brightens so many otherwise drab lives:

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу