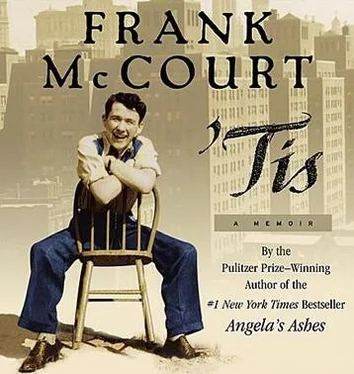

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I’m not destroying. I just want to know where you got the idea that Humpty is an egg.

Because, Mr. McCourt, it’s in all the pictures and whoever drew the first picture musta known the guy who wrote the poem or he’d never have made it an egg.

All right. If you’re content with the idea of egg we’ll let it be but I know the future lawyers in this class will never accept egg where there is no evidence of egg.

As long as there’s no threat of grades they’re comfortable with the matter of childhood and when I suggest they write their own children’s books they don’t complain, they don’t resist.

Oh, yeah, yeah, what a great idea.

They are to write, illustrate and bind their books, original work, and when they’re finished I take them to an elementary school down the street on First Avenue to be read and evaluated by real critics, the ones who would read such books, third and fourth graders.

Oh, yeah, yeah, the little ones, that’d be cute.

On a bitter January day the little ones are brought to Stuyvesant by their teacher. Aw, gee, look at ’em. So c-u-t-e. Look at their little coats and earmuffs and mittens and their little colored boots and their little frozen faces. Aw, cute.

The books are laid out on a long table, books of all sizes, shapes, and the room blazes with color. My students sit and stand, giving up their seats to their little critics who sit on desks, their feet dangling far above the floor. One by one they come to the table to select the books they read and to comment. I’ve already warned my students these small children are poor liars, all they know for the moment is the truth. They read from sheets their teacher helped them prepare.

The book I read is Petey and the Space Spider. This book is okay except for the beginning, the middle and the end.

The author, a tall Stuyvesant junior, smiles weakly and looks at the ceiling. His girlfriend hugs him.

Another critic. The book I read was called Over There and I didn’t like it because people shouldn’t write about war and people shooting each other in the face and going to the bathroom in their pants because they’re scared. People shouldn’t write about things like that when they can write about nice things like flowers and pancakes.

For the little critic there is wild applause from her classmates, from the Stuyvesant authors a stony silence. The author of Over There glares over the head of his critic.

Their teacher had asked her pupils to answer the question, Would you buy this book for yourself or anyone else?

No, I wouldn’t buy this book for me or anyone. I already have this book. It was written by Dr. Seuss.

The critic’s classmates laugh and their teacher tells them shush but they can’t stop and the plagiarist, sitting on the windowsill, turns red and doesn’t know what to do with his eyes. He’s a bad boy, did the wrong thing, gave the little ones ammunition for their jeers, but I want to comfort him because I know why he did that bad thing, that he could hardly be in the mood for creating a children’s book when his parents separated during the Christmas break, that he’s caught in the bitterness of a custody battle, doesn’t know what to do when mother and father pull him in opposite directions, that he feels like running to his grandfather in Israel, that with all this he can meet his English assignment only by stapling together a few pages on which he has copied a Dr. Seuss story and illustrating it with stick figures, that this is surely the lowest point in his life and how do you handle the humiliation when you’re caught in the act by this smartass third grader who stands there laughing in the spotlight. He looks at me across the room and I shake my head, hoping he understands that I understand. I feel I should go to him, put my arm around his shoulder, comfort him, but I hold back because I don’t want third graders or high school juniors to think I condone plagiarism. For the moment I have to hold the high moral ground and let him suffer.

The little ones get into their winter clothes and leave and my classroom is quiet. A Stuyvesant author who suffered negative criticism says he hopes those damn kids get lost in the snow. Another tall junior, Alex Newman, says he feels okay because his book was praised but what those kids did to a few of the authors was disgraceful. He says some of those kids are assassins and there is agreement around the room.

But they’re softened up for the American Literature of the junior year, ready for the rant of Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. We chant Vachel Lindsay and Robert Service and T. S. Eliot, who can be recruited for either side of the Atlantic. We tell jokes because every joke is a short story with a fuse and an explosion. We journey back into childhood for games and street rhymes, Miss Lucy and Ring-around-a-rosy, and visiting educators wonder what’s going on in this classroom.

And tell me, Mr. McCourt, how does that prepare our children for college and the demands of society?

55

On the table by the bed in my mother’s apartment there were bottles of pills, tablets, capsules, liquid medicines, take this for that and that for this three times a day when it’s not four but not when you’re driving or operating heavy machinery, take before, during and after meals avoiding alcohol and other stimulants and be sure you don’t mix your medications, which Mam did, confusing the emphysema pills with the pills for the pain of her new hip and the pills that put her to sleep or woke her up and the cortisone that bloated her and caused hair to grow on her chin so that she was terrified to leave the house without her little blue plastic razor in case she might be away awhile and in danger of sprouting all kinds of hair and she’d be ashamed of her life, so she would, ashamed of her life.

The city provided a woman to care for her, bathe her, cook, take her for walks if she was able for it. When she wasn’t able for it she watched television and the woman watched with her though she reported later that Mam spent much of her time staring at a spot on the wall or looking out the window delighting in the times her grandson, Conor, called up to her and they chatted while he hung from the iron bars that secured her windows.

The woman from the city lined up the pill bottles and warned Mam to take them in a certain order during the night but Mam would forget and become so confused no one knew what she might have done to herself and the ambulance would have to take her to Lenox Hill Hospital where she was now well known.

The last time she was in the hospital I called her from my school to ask how she was.

Ah, I dunno.

What do you mean you dunno?

I’m fed up. They’re sticking things in me and pulling things out of me.

Then she whispered, If you’re coming to see me, would you do me a favor?

I would. What is it?

You’re not to tell anyone about this.

I won’t. What is it?

Will you bring me a blue plastic razor?

A plastic razor? For what?

Never mind. Couldn’t you just bring it and stop asking questions?

Her voice broke and there was sobbing.

All right, I’ll bring it. Are you there?

She could barely talk with the sobbing. And when you come up give the razor to the nurse and don’t come in till she tells you.

I waited while the nurse took in the razor and screened Mam from the world. On her way out, the nurse whispered, She’s shaving. It’s the cortisone. She’s embarrassed.

All right, said Mam, you can come in now and don’t be asking me any questions even if you didn’t do what I asked you.

What do you mean?

I asked you for a blue plastic razor and you brought me a white one.

What’s the difference?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.