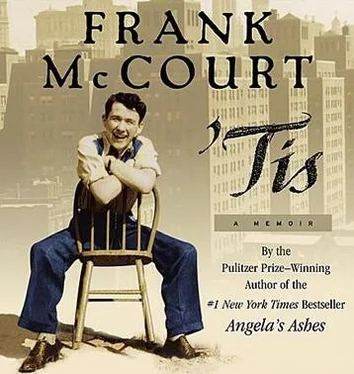

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I shook his hand because that’s all we ever did except for one time when I was in hospital with typhoid and he kissed my forehead. Now he drops my hand, reminds me once more to be a good boy, to obey my mother and remember the power of the daily rosary.

When we returned to his house I told my uncle I’d like to walk through the Protestant area, the Shankill Road. He shook his head. Quiet man. I said, Why not?

Because they’ll know.

What will they know?

They’ll know you’re a Catholic.

How will they know?

Och, they’ll know.

His wife agreed. She said, They have ways.

Do you mean to say you could spot a Protestant if he walked down this street?

We could.

How?

And my uncle smiled. Och, years of practice.

While we had another cup of tea there was shooting down Leeson Street. A woman screamed and when I went to the window Uncle Gerard said, Och, get your head away from the window. One little movement and the soldiers are so nervous they’ll spray it.

The woman screamed again and I had to open the door. She had a child in her arms and another one clinging to her skirt and she was being forced back by a soldier pushing his slanted rifle. She begged him to let her cross Leeson Street to her other children. I thought I’d help by carrying the child clinging to her but when I went to pick her up the woman dashed around the soldier and across the street. The soldier swung on me and put his rifle barrel against my forehead. Get inside, Paddy, or I’ll blow your fawking head off.

My uncle and his wife, Lottie, told me that was a foolish thing I did and it helped no one. They said that whether you were Catholic or Protestant there was a way of handling things in Belfast that outsiders would never understand.

Still, on my way back to the hotel in a Catholic taxi, I dreamed I could easily roam Belfast with an avenging flamethrower. I’d aim it at that bastard in his red beret and reduce him to cinders. I’d pay back the Brits for the eight hundred years of tyranny. Oh, by Jesus, I’d do my bit with a fifty-caliber machine gun. I would, indeed, and I was ready to sing “Roddy McCorley goes to die on the bridge of Toome today,” till I remembered that that was my father’s song and decided instead I’d have a nice quiet pint with Paddy and Kevin in the bar of our Belfast hotel and before I went to sleep that night I’d call Alberta so that she could hold the phone to Maggie and I’d carry my daughter’s gurgle into my dreams.

Mam flew over and stayed with us awhile at our rented flat in Dublin. Alberta went shopping on Grafton Street and Mam strolled with me to St. Stephen’s Green with Maggie in her pram. We sat by the water and threw crumbs to ducks and sparrows. Mam said it was lovely to be in this place in Dublin in the latter end of August the way you could feel autumn coming in with the odd leaf drifting before you and the light changing on the lake. We looked at children wrestling in the grass and Mam said it would be lovely to stay here a few years and see Maggie grow up with an Irish accent, not that she had anything against the American accent, but wasn’t it a pure pleasure to listen to these children and she could see Maggie growing and playing on this very grass.

When I said it would be lovely a shiver went through me and she said someone was walking on my grave. We watched the children play and looked at the light on the water and she said, You don’t want to go back, do you?

Back where?

New York.

How do you know that?

I don’t have to lift the lid to know what’s in the pot.

The porter at the Shelbourne Hotel said it would be no bother at all to keep an eye on Maggie’s pram against the railings outside while we sat in the lounge, a sherry for Mam, a pint for me, a bottle of milk for Maggie on Mam’s lap. Two women at the next table said Maggie was a dote, a right dote she was, oh gorgeous, and wasn’t she the spittin’ image of Mam herself. Ah, no, said Mam, I’m only the grandmother.

The women were drinking sherry like my mother but the three men were lowering pints and you could see from their tweed caps, red faces and great red hands they were farmers. One, with a dark green cap, called to my mother, The little child might be a lovely child, missus, but you’re not so bad yourself.

Mam laughed and called back to him, Ah, sure, you’re not so bad either.

Begod, missus, if you were a little older I’d run away with you.

Well, said Mam, if you were a little younger I’d go.

People all around the lounge were laughing and Mam threw her head back and laughed herself and you could see from the shine in her eyes she was having the time of her life. She laughed till Maggie whimpered and Mam said the child had to be changed and we’d have to go. The man with the dark green cap put on a begging act. Yerra, don’t go, missus. Your future is with me. I’m a rich widow man with a farm o’ land.

Money isn’t everything, said Mam.

But I have a tractor, missus. We could ride together and how would that suit you?

It stirs me, said Mam, but I’m still a married woman and when I put on the widow’s weeds you’ll be the first to know.

Fair enough, missus. I live in the third house on the left as you enter the southwest coast of Ireland, a grand place called Kerry.

I heard of it, said Mam. ’Tis known for sheep.

And powerful rams, missus, powerful.

You’re never short of an answer, are you?

Come to Kerry with me, missus, and we’ll walk the hills wordless.

Alberta was already at the flat making lamb stew and when Kevin Sullivan dropped in with Ben Kiely, the writer, there was enough for everyone and we drank wine and sang because there isn’t a song in the world Ben doesn’t know. Mam told the story of our time in the Shelbourne Hotel. Lord above, she said, that man had a way with him and if it wasn’t for Maggie needing to be changed and wiped I’d be on my way to Kerry.

In the nineteen seventies Mam was in her sixties. The emphysema that came from years of smoking left her so breathless she dreaded leaving her apartment anymore and the more she stayed at home the heavier she grew. For a while she came to Brooklyn to take care of Maggie on weekends but that stopped when she could no longer climb the subway stairs. I accused her of not wanting to see her granddaughter.

I do want to see her but ’tis hard for me to get around anymore.

Why don’t you lose weight?

’Tis hard for an elderly woman to lose weight and anyway why should I?

Don’t you want to have some kind of life where you’re not sitting in your apartment all day looking out the window?

I had my life, didn’t I, and what use was it? I just want to be left alone.

There were attacks which left her gasping and when she visited Michael in San Francisco he had to rush her to the hospital. We told her she was ruining our lives the way she always got sick on holidays, Christmas, New Year’s Eve, Easter. She shrugged and laughed and said, Pity about ye now.

No matter how her health was, no matter how breathless, she climbed the hill to the Broadway bingo hall till she fell one night and broke her hip. After the operation she was sent to an upstate convalescent home and then stayed with me at a summer bungalow in Breezy Point at the tip of the Rockaway Peninsula. Every morning she slept late and when she woke sat slumped on the side of her bed, staring out the window at a wall. After a while she’d drag herself into the kitchen for breakfast and when I barked at her for eating too much bread and butter, that she’d be the size of a house, she barked back at me, For the love o’ Jesus, leave me alone. The bread and butter is the only comfort I have.

52

When Henry Wozniak taught Creative Writing and English and American Literature he wore a shirt, a tie and a sports jacket every day. He was faculty adviser to the Stuyvesant High School literary magazine, Caliper, and to the students’ General Organization, and he was active in the union, the United Federation of Teachers.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.