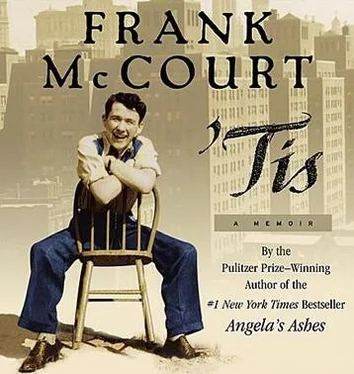

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On streets and in subways I’d meet former students from McKee High School who would tell me of the boys who went to Vietnam, heroes when they left and now home in body bags. Bob Bogard called to tell me about the funeral of a boy who had been in both our classes but I didn’t go because I knew that on Staten Island there would be pride in this blood sacrifice. The boys from Staten Island would fill more body bags than Stuyvesant could ever imagine. Mechanics and plumbers had to fight while college students shook indignant fists, fornicated in the fields of Woodstock and sat in.

In my classroom I wore no buttons, took no sides. There was enough ranting all around us and, for me, picking my way through five classes was minefield enough.

Mr. McCourt, why can’t our classes be relevant?

Relevant to what?

Well, you know, look at the state of the world. Look at what’s happening.

There’s always something happening and we could sit in this classroom for four years clucking over headlines and going out of our minds.

Mr. McCourt, don’t you care about the babies burned with napalm in Vietnam?

I do, and I care about the babies in Korea and China, in Auschwitz and Armenia, and the babies impaled on the lances of Cromwell’s soldiers in Ireland. I told them what I’d learned from my part-time teaching at New York Technical College in Brooklyn, from my class of twenty-three women, most from the Islands, and from my five men. There was a fifty-five-year-old working for a college degree so that he could return to Puerto Rico and spend the rest of his life helping children. There was a young Greek studying English so that he could work toward a Ph.D. in the literature of Renaissance England. There were three young African-American men in the class and when one, Ray, complained he’d been bothered by the police on a subway platform because he was black the women from the Islands had no patience with him. They told him if he stayed home and studied he wouldn’t be getting into trouble and no kid of theirs would come home with a story like that. They’d break his head. Ray was quiet. You don’t talk back to women from the Islands.

Denise, now in her late twenties, was often late to class and I threatened her with failure till she wrote an autobiographical essay which I asked her to read to the class.

Oh no, she couldn’t do that. She’d be ashamed to let people know she had two children whose father had left her to return to Montserrat and never sends her a penny. No, she wouldn’t mind if I read the essay to the class if I didn’t tell who wrote it.

She had described a day in her life. She’d wake early to do her Jane Fonda video exercises while thanking Jesus for the gift of another day. She’d take a shower, get her children up, her eight-year-old, her six-year-old, and take them to school and after that she’d rush to her college classes. In the afternoon she’d go straight to her job at a bank in downtown Brooklyn and from there to her mother’s house. Her mother had already picked up the children from school and without her Denise didn’t know what she’d do especially when her mother had that terrible disease that makes your fingers curl up in knots and Denise didn’t know how to spell. After taking the children home, putting them to bed and getting their clothes ready for the next morning, Denise would pray by the side of her bed, look up at the cross, thank Jesus once more for another wonderful day and try to fall asleep with His suffering image in her dreams.

The women from the Islands thought that was a wonderful story and looked at each other wondering who wrote it and when Ray said he didn’t believe in Jesus they told him shut up, what did he know hanging around subway platforms? They worked, took care of their families, went to school and this was a wonderful country where you could do what you liked even if you were black like the night and if he didn’t like it he could go back to Africa if he could ever find it without getting hassled by the police.

I told the women they were heroes. I told the Puerto Rican man he was a hero and I told Ray if he ever grew up he could be a hero, too. They looked at me, puzzled. They didn’t believe me and you could guess what was running through their minds, that they were doing only what they were supposed to do, getting an education, and why was this teacher calling them heroes?

My Stuyvesant students were not satisfied. Why was I telling them stories of women from the Islands and Puerto Ricans and Greeks when the world was going to hell?

Because the women from the Islands believe in education. You can demonstrate and shake your fists, burn your draft cards and block the traffic with your bodies, but what do you know in the end? For the ladies from the Islands there is one relevance, education. That is all they know. That is all I know. That is all I need to know.

Still, there was a confusion and a darkness in my head and I had to understand what I was doing in this classroom or get out. If I had to stand before those five classes I couldn’t let days dribble by in the routine of high school grammar, spelling, vocabulary, digging for the deeper meaning in poetry, bits of literature doled out for the multiple choice tests that would follow so that universities can be supplied with the best and the brightest. I had to begin enjoying the act of teaching and the only way I could do that was to start over, teach what I loved and to hell with the curriculum.

The year Maggie was born I told Alberta something my mother used to say, that a child gains her vision at six weeks and if that was true we should take her to Ireland so that her first image would be of moody Irish skies, a passing shower with the sun shining through.

Paddy and Mary Clancy invited us to stay on their farm in Carrick-on-Suir but newspapers were saying Belfast was in flames, a nightmare city, and I was anxious to see my father. I traveled north with Paddy Clancy and Kevin Sullivan and the night we arrived we walked the streets of Catholic Belfast. The women were out banging on the pavements with the lids of garbage cans, warning their men of approaching army patrols. They were suspicious of us till they recognized Paddy of the famous Clancy Brothers and we passed on without trouble.

Next day Paddy and Kevin stayed in the hotel while I went to my Uncle Gerard’s house so that he could take me to my father in Andersonstown. When my father opened his door he nodded at Uncle Gerard and looked through me. Uncle said, This is your son.

My father said, Is it little Malachy?

No. I’m your son Frank.

Uncle Gerard said, It’s a sad thing when your own father doesn’t know you.

My own father said, Come in. Sit down. Will you have a cup of tea?

He offered the tea but showed no signs of making it in his little kitchen till a woman came from next door and did it. Uncle Gerard whispered, See that. He never lifts a finger. He doesn’t have to with the way the ladies of Andersonstown wait on him hand and foot. They tempt him daily with soup and dainty things.

My father smoked his pipe but never touched his mug of tea. He was busy asking about my mother and three brothers. Och, your brother Alphie came to see me. Quiet lad your brother Alphie. Och, aye. Quiet lad. And you’re all well in America? Attending to your religious duties? Och, you have to be good to your mother and attend to your religious duties.

I wanted to laugh. Jesus, is this man preaching? I wanted to say, Dad, have you no memory?

No, what’s the use. I’d be better off leaving my father to his demons though you could see from the peaceful way he had with his pipe and his mug of tea that the demons wouldn’t cross his threshold. Uncle Gerard said we ought to leave before darkness fell on Belfast and I wondered how I should say good-bye to my father. Shake his hand? Embrace him?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.