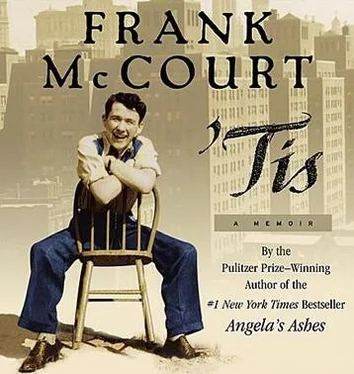

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And that makes me feel happier than anything.

The minute I turn off Barrington Street and down the hill to the lane I hear people saying, Oh, God, here’s Frankie McCourt in his American uniform. Kathleen O’Connell is at the door of her shop laughing and offering me a piece of Cleeve’s toffee. Sure, didn’t you always love that, Frankie, even if it destroyed the teeth of Limerick. Her niece is here, too, the one that lost an eye when the knife she was using to open a bag of potatoes slipped and went into her head. She’s laughing over the Cleeve’s toffee, too, and I’m wondering how you can still laugh with an eye gone.

Kathleen calls down to the little fat woman at the corner of the lane, He’s here, Mrs. Patterson, a regular film star he is. Mrs. Patterson takes my face in her hands and tells me, I’m happy for your poor mother, Frankie, the terrible life she had.

And there’s Mrs. Murphy who lost her husband at sea in the war, living now in sin with Mr. White, nobody in the lanes the slightest bit shocked, and smiling at me, You are a film star, indeed, Frankie, and how’s your poor eyes. Sure, they look grand.

The whole lane is out standing at doors and telling me I’m looking grand. Even Mrs. Purcell is telling me I’m looking grand and she’s blind. But I understand that’s what she’d tell me if she could see and when I come near her she holds out her arms and tells me, Come here outa that, Frankie McCourt, and give me a hug for the sake of the days we listened to Shakespeare and Sean O’Casey on the wireless together.

And when she puts her arms around me she says, Arrah, God above, there isn’t a pick on you. Aren’t they feeding you in the American army? But what matter, you smell grand. They always smell grand, the Yanks.

It’s hard for me to look at Mrs. Purcell and the delicate eyelids that barely flutter on the eyes set back in her head and remember the nights when she let me sit in the kitchen listening to plays and stories on the wireless and the way she’d think nothing of giving me a mug of tea and a big cut of bread and jam. It’s hard because the people in the lane are at their doors delighted and I’m ashamed of myself for walking away from my mother and sulking on the bed in the National Hotel. How could she explain to the neighbors that she met me at the station and I wouldn’t come home? I’d like to walk the few steps to my mother at her door and tell her how sorry I am but I can’t say a word for fear the tears might come and she’d say, Oh, your bladder is near your eye.

I know she’d say that to bring on a laugh and keep her own tears back so that we wouldn’t all feel shy and ashamed of our tears. All she can do now is say what any mother would in Limerick, You must be famished. Would you like a nice cup of tea?

My Uncle Pat is sitting in the kitchen and when he lifts his face to me it makes me sick to see the redness of his eyes and the yellow ooze. It reminds me of little Scabby Eyes over at the Lyric Cinema. It reminds me of myself.

Uncle Pat is my mother’s brother and he’s known all over Limerick as Ab Sheehan. Some people call him the Abbot and no one knows why. He says, That’s a grand uraform you have there, Frankie. Where’s your big gun? He laughs and shows the yellow stubs of teeth in his gums. His hair is black and gray and thick on his head from not being washed and there’s dirt in the creases on his face. His clothes, too, shine with the grease of not being washed and I wonder how my mother can live with him and not keep him clean till I remember how stubborn he is about not washing himself and wearing the same clothes day and night till they fall from his body. My mother couldn’t find the soap once and when she asked him if he had seen it he said, Don’t be blamin’ me for the soap. I didn’t see the soap. I didn’t wash meself in a week. And he said it as if everyone should admire him. I’d like to strip him in the backyard and hose him down with hot water till the dirt left the creases on his face and the pus ran from his eyes.

Mam makes the tea and it’s good to see she has decent cups and saucers now not like the old days when we drank from jam jars. The Abbot refuses the new cups. I want me own mug, he says. My mother argues with him that this mug is a disgrace with all the dirt in the cracks where all kinds of diseases might be lurking. He doesn’t care. He says, That was me mother’s mug that she left to me, and there’s no arguing with him when you know he was dropped on his head in his infancy. He gets up to limp out to the backyard lavatory and when he’s gone Mam says she did everything to move him out of this house and stay with her for a while. No, he won’t go. He’s not going to leave his mother’s house and the mug she gave him long ago and the little statue of the Infant of Prague and the big picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus above in the bedroom. No, he’s not going to leave all that. What matter. Mam has Michael and Alphie to take care of, Alphie still in school and poor Michael washing dishes down at the Savoy Restaurant, God help him.

We finish our tea and I take a walk with Alphie down O’Connell Street so that everyone will see me and admire me. We meet Michael coming up the street from his job and there’s a pain in my heart when I see him, the black hair falling down to his eyes and his body a bag of bones with clothes as greasy as the Abbot’s from washing dishes all day. He smiles in his shy way and says, God, you’re looking very fit, Frankie. I smile back at him and I don’t know what to say because I’m ashamed of the way he looks and if my mother were here I’d yell at her and ask her why Michael has to look like this. Why can’t she get him decent clothes or why can’t the Savoy Restaurant at least give him an apron to save himself from the grease? Why did he have to leave school at fourteen to wash dishes? If he came from the Ennis Road or the North Circular Road he’d be in school now playing rugby and going to Kilkee on his holidays. I don’t know what’s the use of coming back to Limerick where children are still running around in bare feet and looking at the world through scabby eyes, where my brother Michael has to wash dishes and my mother takes her time moving to a decent house. This is not the way I expected it to be and it makes me so sad I wish I were back in Germany drinking beer in Lenggries.

Some day I’ll get them out of here, my mother, Michael, Alphie, over to New York where Malachy is already working and ready to join the air force so that he won’t be drafted and sent to Korea. I don’t want Alphie to leave school at the age of fourteen like the rest of us. At least he’s at the Christian Brothers and not a National school like Leamy’s, the one we went to. Some day he’ll be able to go to secondary school so that he’ll know Latin and other important things. Now at least he has clothes and shoes and food and he needn’t be ashamed of himself. You can see how sturdy he is, not like Michael, the bag of bones.

We turn and make our way back up O’Connell Street and I know people are admiring me in my GI uniform till some call out, Jesus, is that you, Frankie McCourt? and the whole world knows I’m not a real American GI, that I’m just someone from the back lanes of Limerick all togged out in the American uniform with the corporal’s stripes.

My mother is coming down the street all smiles. The new house will have electricity and gas tomorrow and we can move in. Aunt Aggie sent word she heard I’d arrived and she wants us to come over for tea. She’s waiting for us now.

Aunt Aggie is all smiles, too. It’s not like the old days when there was nothing in her face but bitterness over not having children of her own and even if there was bitterness she was the one who made sure I had decent clothes for my first job. I think she’s impressed with my uniform and my corporal’s stripes the way she keeps asking if I’d like more tea, more ham, more cheese. She’s not that generous with Michael and Alphie and you can see it’s up to my mother to make sure they have enough. They’re too shy to ask for more or they’re afraid. They know she has a fierce temper from not having children of her own.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.