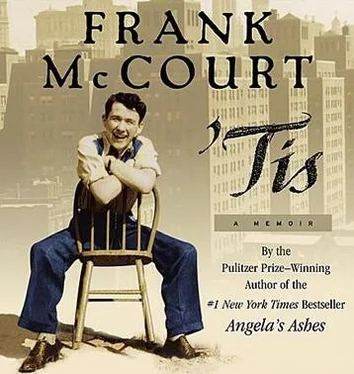

Frank McCourt - 'Tis

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Frank McCourt - 'Tis» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Старинная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:'Tis

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

'Tis: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «'Tis»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

'Tis — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «'Tis», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All the way on the train to Frankfurt I’m dreaming of the new house and the comfort it’s bringing my mother and my brothers, Michael and Alphie. You’d think that after all the miserable days in Limerick I wouldn’t even want to go back to Ireland but when the plane approaches the coast and the shadows of clouds are moving across the fields and it’s all green and mysterious I can’t stop myself from crying. People look at me and it’s a good thing they don’t ask me why I’m crying. I wouldn’t be able to tell them. I wouldn’t be able to describe the feeling that came around my heart about Ireland because there are no words for it and because I never knew I’d feel this way. It’s strange to think there are no words for the way I feel unless they’re in Shakespeare or Samuel Johnson or Dostoyevsky and I didn’t notice them.

My mother is at the railway station to meet me, smiling with her new white teeth, togged out in a bright new frock and shiny black shoes. My brother Alphie is with her. He’s going on twelve and wearing a gray suit that must have been his confirmation suit last year. You can see he’s proud of me, especially my corporal’s stripes, so proud he wants to carry my duffel bag. He tries but it’s too heavy and I can’t let him drag it along the ground because of the cuckoo clock and the Dresden china I brought my mother.

I feel proud myself knowing that people are looking at me in my American army uniform. It isn’t every day you see an American corporal getting off the train at the Limerick railway and I can’t wait to walk the streets knowing the girls are going to be whispering, Who’s that? Isn’t he gorgeous? They’ll probably think I fought the Chinese hand to hand in Korea, that I’m back for a rest from the serious wound which I’m too brave to show.

When we leave the station and walk to the street I know we’re not going the right way. We should be going toward Janesboro and the new house, instead we’re walking by the People’s Park the way we did when we first came from America and I want to know why we’re going to Grandma’s house in Little Barrington Street. My mother says that, well, the electricity and the gas aren’t in the new house yet.

Why not?

Well, I didn’t bother.

Why didn’t you bother?

Wisha, I don’t know.

That puts me in a rage. You’d think she’d be glad to be out of that slum in Little Barrington Street and up there in her new house planting flowers and making tea in her new kitchen that looks out on the garden. You’d think she’d be longing for the new beds with the clean sheets and no fleas and a bathroom. But no. She has to hang on to the slum and I don’t know why. She says ’tis hard moving out and leaving her brother, my Uncle Pat, that he’s not well in himself and barely hobbling. He still sells papers all around Limerick but, God help him, he’s a bit helpless and didn’t he let us stay in that house when we were in a bad way. I tell her I don’t care, I’m not going back to that house in the lane. I’ll stay here in the National Hotel till she gets the electricity and gas up in Janesboro. I hoist my duffel bag to my shoulder and when I walk away she whimpers after me, Oh, Frank, Frank, one night, one last night in my mother’s house, sure it wouldn’t kill you, one night.

I stop and turn and bark at her, I don’t want one night in your mother’s house. What the hell is the use of sending you the allotment if you want to live like a pig?

She cries and reaches her arms to me and Alphie’s eyes are wide, but I don’t care. I sign in at the National Hotel and throw my duffel bag on the bed and wonder what kind of a stupid mother I have who’ll stay in a slum a minute more than she has to. I sit on the bed in my American army uniform and my new corporal’s stripes and wonder if I should stay here in a fit of rage or walk the streets so that the world can admire me. I look out the window at Tait’s clock, the Dominican church, the Lyric Cinema beyond where small boys are waiting at the entrance to the gods where I used to go for tuppence. The boys are raggedy and rowdy and if I sit at this window long enough I can imagine I’m looking back at my own days in Limerick. It’s only ten years since I was twelve and falling in love with Hedy Lamarr up there on the screen with Charles Boyer, the two of them in Algiers and Charles saying, Come wiz me to ze Casbah. I went around saying that for weeks till my mother begged me to stop. She loved Charles Boyer herself and she’d prefer to hear it from him. She loved James Mason, too. All the women in the lane loved James Mason, he was so handsome and dangerous. They all agreed it was the dangerous part they loved. Sure a man without danger is hardly a man at all. Melda Lyons would tell all the women in Kathleen O’Connell’s shop how she was mad for James Mason and they’d laugh when she said, Bejesus, if I met him I’d have him naked as an egg in a minute. That would make my mother laugh harder than anyone in Kathleen O’Connell’s shop and I wonder if she’s over there now telling Melda and the women how her son Frank got off the train and wouldn’t come home for a night and I wonder if the women will go home and say Frankie McCourt is back in his American uniform and he’s too high and mighty now for his poor mother below there in the lane though we should have known for he always had the odd manner like his father.

It wouldn’t kill me to walk over to my grandmother’s house this one last time. I’m sure my brothers Michael and Alphie are bragging to the whole world that I’m coming home and they’ll be sad if I don’t stroll down the lane in my corporal’s stripes.

The minute I go down the steps of the National Hotel the boys at the Lyric Cinema call across Pery Square, Hoi, Yankee soldier, yoo hoo, do you have any choon gum? Do you have a spare shilling in your pocket or a bar of candy in your pocket?

They pronounce candy like Americans and that makes them laugh so hard they fall against each other and the wall.

There’s one boy off to the side who stands with his hands in his pockets and I can see he has two red scabby eyes in a face full of pimples and a head shaved to the bone. It’s hard for me to admit that’s the way I looked ten years ago and when he calls across the square, Hoi, Yankee soldier, turn around so we can all see your fat arse, I want to give him a good fong in his own scrawny arse. You’d think he’d have respect for the uniform that saved the world even if I’m only a supply clerk now with dreams of getting my dog back. You’d think Scabby Eyes would notice my corporal’s stripes and have a bit of respect but no, that’s the way it is when you grow up in a lane. You have to pretend you don’t give a fiddler’s fart even when you do.

Still, I’d like to cross the square to Scabby Eyes and shake him and tell him he’s the spitting image of me when I was his age but I didn’t stand outside the Lyric Cinema tormenting Yanks over their fat arses. I’m trying to convince myself that’s the way I was myself, till another part of my mind tells me I wasn’t a bit different from Scabby Eyes, that I was just as liable as him to torment Yanks or Englishmen or anyone with a suit or a fountain pen in his top pocket riding around on a new bike, that I was just as liable to throw a rock through the window of a respectable house and run away laughing one minute and raging the next.

All I can do now is walk away keeping myself twisted to the wall so that Scabby Eyes and the boys won’t see my arse and have ammunition.

It’s all confusion and dark clouds in my head till the other idea comes. Go back to the boys like a GI from the films and give them change from your pocket. It won’t kill you.

They watch me coming and they look as if they’re about to run though no one wants to be a coward and run first. When I dole out the change all they can say is, Ooh, God, and the different way they look at me makes me feel happy. Scabby Eyes takes his share and says nothing till I’m walking away and he calls after me, Hey, mister, sure you don’t have any arse at all at all.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «'Tis»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «'Tis» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «'Tis» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.