And if you stay a bit longer and my voice doesn’t give out, I’ll sing you the song that decided the destiny of this life of mine. I haven’t sung it for thirty years and maybe my voice isn’t up to it. I don’t know why I’m offering, I’ll dedicate it to that woman with the long neck, and to the power a face has to surface again in another’s, maybe that’s what’s touched a chord. And to you, young Italian, coming here every evening, I can see you’re hungry for true stories to turn them into paper, so I’ll make you a present of this story you’ve heard. You can even write down the name of the man who told it to you, but not the name they know me by in this bar, which is a name for tourists passing through. Write that this is the true story of Lucas Eduino who killed the woman he’d thought was his, with a harpoon, in Porto Pim.

Oh, there was just one thing she hadn’t lied to me about; I found out at the trial. She really was called Yeborath. If that’s important at all.

Always so feverish, and with those long limbs waving about. Not rounded at all, so they don’t have the majesty of complete, rounded shapes sufficient unto themselves, but little moving heads where all their strange life seems to be concentrated. They arrive sliding across the sea, but not swimming, as if they were birds almost, and they bring death with frailty and graceful ferocity. They’re silent for long periods, but then shout at each other with unexpected fury, a tangle of sounds that hardly vary and don’t have the perfection of our basic cries: the call, the love cry, the death lament. And how pitiful their lovemaking must be: and bristly, brusque almost, immediate, without a soft covering of fat, made easy by their threadlike shape which excludes the heroic difficulties of union and the magnificent and tender efforts to achieve it.

They don’t like water, they’re afraid of it, and it’s hard to understand why they bother with it. Like us they travel in herds, but they don’t bring their females, one imagines they must be elsewhere, but always invisible. Sometimes they sing, but only for themselves, and their song isn’t a call to others, but a sort of longing lament. They soon get tired and when evening falls they lie down on the little islands that take them about and perhaps fall asleep or watch the moon. They slide silently by and you realize they are sad.

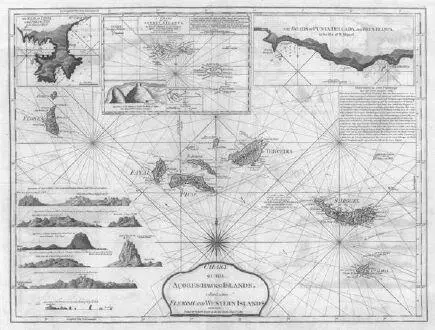

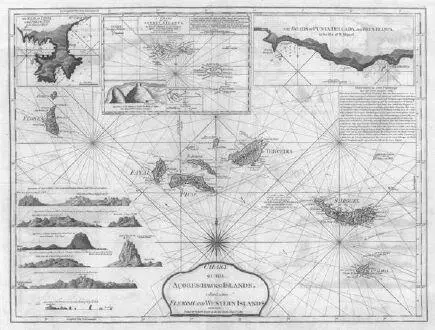

The Azores archipelago is situated in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, about halfway between Europe and America, between latitudes 36°55′ and 39°44′N and longitudes 25° to 31°W. It is composed of nine islands: Santa Maria, São Miguel, Terceira, Graciosa, São Jorge, Pico, Faial, Flores and Corvo. The archipelago stretches across a distance of around 600 km from NW to SE. The name Azores is the result of an error on the part of the first Portuguese sailors; they mistook for sparrow-hawks (in Portuguese, açores ) what in fact were numerous kites which populate the islands.

Portuguese colonization began in 1432 and went on for the whole of the fifteenth century, though at the same time the Azores also became the home of a large number of Flemish colonists, this as a result of marriages which linked the Portuguese throne with Flanders. The Flemish colonists left a considerable mark, not just on the physical features of the inhabitants, but also on the islands’ popular music and folklore in general. The soil is volcanic in origin. The rocky coasts are often made up of sheets of extremely hard lava, while in flatter areas there are stretches of pulverized pumice stone. The physical characteristics of the landscape show very clear signs of volcanic and seismic activity. As well as a whole series of minor volcanic phenomena (smokeholes, geysers, warm springs and mud swamps, etc.), there is an abundance of volcanic lakes which have taken over ancient craters, and the landscape is often broken by deep crevices scored out by the burning lava. The hinterland and the mountains have a savage and often gloomy beauty. The highest peak is Pico, which is 2,345 metres high and located on the island of the same name. Innumerable volcanic eruptions have been recorded: the most terrifying earthquakes took place in 1522, 1538, 1591, 1630, 1755, 1810, 1862, 1884, 1957. The effects of the 1978 earthquake, which hit the island of Terceira in particular, are clearly visible to any traveler stopping over in Angra. In the course of this incessant volcanic activity, the landscape of the Azores has been subjected to considerable change and countless little islands have surfaced and then disappeared. The most curious anecdote in this regard was told by an English sea captain, Tillard. In 1810, on board his warship, the Sabrina, Tillard witnessed the birth of a little island on which he had two men land with an English flag, claiming possession of the territory for the English crown and baptizing it Sabrina. But the day after, before lifting anchor, Captain Tillard was to find to his disappointment that the island of Sabrina had disappeared and the sea was as flat and calm as ever.

The climate of the Azores is mild, with abundant but brief rainfalls and very hot summers. Nature is luxuriant and there are countless species of plants. Typically Mediterranean flora, in which cedars, vines, orange trees and pines dominate, flourishes alongside tropical vegetation which includes pineapple trees, banana trees, passion fruit and a huge variety of flowers. Birds and butterflies abound, but there are no reptiles. Whale hunting, using the traditional methods described in this book, is now practiced only in Pico and Faial. In our century, the emigration of large numbers of people, for mainly economic reasons, has considerably depleted the archipelago’s population. Corvo, Flores and Santa Maria are almost uninhabited.