Art. 66. It is expressly forbidden to throw loose harpoons (that is, not secured to the boat with a rope) at a whale, whatever the circumstances. Anyone who does so does not establish any right over the whale harpooned.

Art. 68. No boat shall, without authorization, cut the ropes of other boats, unless forced to do so to preserve their own safety.

Art. 69. Harpoons, ropes, registration numbers, etc., found on a whale by other boats shall be returned to their rightful owners, nor does returning such items give any right to remuneration or indemnity.

Art. 70. It is forbidden to harpoon or kill whales of the Balaena species, commonly known as French whales.

Art. 71. It is forbidden to harpoon or kill female whales surprised while suckling their young, or young whales still at suckling age.

Art. 72. In order to preserve the species and better exploit hunting activities, it will be the responsibility of the Minister for the Sea to establish the sizes of the whales which may be caught and the periods of close season, to set quotas for the number of whales which may be hunted, and to introduce any other restrictive measures considered necessary.

Art. 73. The capture of whales for scientific purposes may be undertaken only after obtaining ministerial authorization.

Art. 74. It is expressly forbidden to hunt whales for sport.

“Regulations Governing the Hunting of Whales,” published in the Diário do Governo, 19.5.54 and still in force

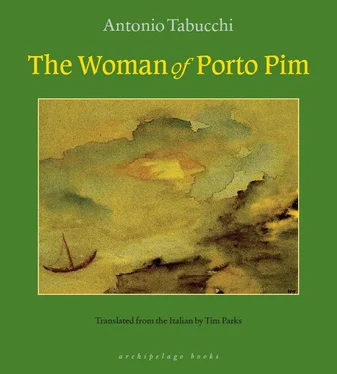

On the first Sunday in August the whalemen hold their annual festival in Horta. They line up their freshly painted boats in Porto Pim bay, the bell briefly rings out two hoarse clangs, the priest forms and climbs up to the promontory dominating the bay, where stands the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Guia. Behind the priest walk the women and children, with the whalemen bringing up the rear, each with his harpoon on his shoulder. They are very contrite and dressed in black. They all go into the chapel to hear Mass, leaving their harpoons standing against the wall outside, one next to the other, the way people elsewhere park their bicycles.

The harbor office is closed, but Senhor Chaves invites me in just the same. He is a distinguished, polite man with an open, slightly ironic smile and the blue eyes of some Flemish ancestor. There are hardly any left, he tells me, I don’t think it’ll be easy to find a boat. I ask if he means sperm whales and he laughs, amused. No, whalemen, he specifies, they’ve all emigrated to America, everybody in the Azores emigrates to America, the Azores are deserted, haven’t you noticed? Yes, of course I have, I say, I’m sorry. Why? he asks. It’s an embarrassing question. Because I like the Azores, I reply without much logic. So you’ll like them even more deserted, he objects. And then he smiles as if to apologize for having been brusque. In any event, you see about getting yourself some life insurance, he concludes, otherwise I can’t give you a permit. As for getting you on board, I’ll sort that out, I’ll speak to António José, who may be going out tomorrow, it seems there’s a herd on the way. But I can’t promise you a permit for more than two days.

A H

UNT

It’s a herd of six or seven, Carlos Eugénio tells me, his satisfied smile showing off such a brilliant set of false teeth it occurs to me he might have carved them himself from whale ivory. Carlos Eugénio is seventy, agile and still youthful, and he is mestre baleeiro, which, literally translated, means “master whaler,” though in reality he is captain of this little crew and has absolute authority over every aspect of the hunt. The motor launch leading the expedition is his own, an old boat about ten metres long, which he maneuvers with deftness and nonchalance, and without any hurry either. In any event, he tells me, the whales are splashing about, they won’t run away. The radio is on so as to keep in contact with the lookout based on a lighthouse on the island; a monotonous and it seems to me slightly ironic voice thus guides us on our way. “A little to the right, Maria Manuela,” says the grating voice, “you’re going all over the place.” Maria Manuela is the name of the boat. Carlos Eugénio makes a gesture of annoyance, but still laughing, then he turns to the sailor who is riding with us, a lean, alert man, a boy almost, with constantly moving eyes and a dark complexion. We’ll manage on our own, he decides, and turns the radio off. The sailor climbs nimbly up the boat’s only mast and perches on the crosspiece at the top, wrapping his legs around. He too points to the right. For a moment I think he’s sighted them, but I don’t know the whaleman’s sign language. Carlos Eugénio explains that an open hand with the index finger pointing upward means “whales in sight,” and that wasn’t the gesture our lookout made.

I turn to glance at the sloop we are towing. The whalemen are relaxed, laughing and talking together, though I can’t make out what they’re saying. They look as though they’re out on a pleasure cruise. There are six of them and they’re sitting on planks laid across the boat. The harpooner is standing up, though, and appears to be following our lookout’s gestures with attention: he has a huge paunch and a thick beard, young, he can’t be more than thirty. I’ve heard they call him Chá Preto, Black Tea, and that he works as a docker in the port in Horta. He belongs to the whaling cooperative in Faial, and they tell me he’s an exceptionally skilled harpooner.

I don’t notice the whale until we’re barely three hundred metres: a column of water rises against the blue as when some pipe springs a leak in the road of a big city. Carlos Eugénio has turned off the engine and only our momentum takes us drifting on towards that black shape lying like an enormous bowler hat on the water. In the sloop the whalemen are silently preparing for the attack: they are calm, quick, resolute, they know the motions they have to go through by heart. They row with powerful, well-spaced strokes, and in a flash they are far away. They go round in a wide circle, approaching the whale from the front so as to avoid the tail, and because if they approached from the sides they would be in sight of its eyes. When they are a hundred metres off they draw their oars into the boat and raise a small triangular sail. Everybody adjusts sail and ropes: only the harpooner is immobile on the point of the prow: standing, one leg bent forward, the harpoon lying in his hand as if he were measuring its weight. He concentrates, hanging on for the right moment, the moment when the boat will be near enough for him to strike a vital point, but far enough away not to be caught by a lash of the wounded whale’s tail. Everything happens with amazing speed in just a few seconds. The boat makes a sudden turn while the harpoon is still curving through the air. The instrument of death isn’t flung from above downwards, as I had expected, but upwards, like a javelin, and it is the sheer weight of the iron and the speed of the thing as it falls that transforms it into a deadly missile. When the enormous tail rises to whip first the air then the water, the sloop is already far away. The oarsmen are rowing again, furiously, and a strange play of ropes, which until now was going on underwater so that I hadn’t seen it, suddenly becomes visible and I realize that our launch is connected to the harpoon too, while the whaling sloop has jettisoned its own rope. From a straw basket placed in a well in the middle of the launch, a thick rope begins to unwind, sizzling as it rushes through a fork on the bow; the young deckhand pours a bucket of water over it to cool it and prevent it snapping from the friction. Then the rope tightens and we set off with a jerk, a leap, following the wounded whale as it flees. Carlos Eugénio holds the helm and chews the stub of a cigarette; the sailor with the boyish face watches the sperm whale’s movements with a worried expression. In his hand he holds a small sharp axe ready to cut the rope if the whale should go down, since it would drag us with it underwater. But the breathless rush doesn’t last long. We’ve hardly gone a kilometre when the whale stops dead, apparently exhausted, and Carlos Eugénio has to put the launch into reverse to stop the momentum from taking us on top of the immobile animal. He struck well, he says with satisfaction, showing off his brilliant false teeth. As if in confirmation of his comment, the whale, whistling, raises his head right out of the water and breathes; and the jet that hisses up into the air is red with blood. A pool of vermilion spreads across the sea and the breeze carries a spray of red drops as far as our boat, spotting faces and clothes. The whaling sloop has drawn up against the launch: Chá Petro throws his tools up on deck and climbs up himself with an agility truly surprising for a man of his build. I gather that he wants to go on to the next stage of the attack, the lance, but the mestre seems not to agree. There follows some excited confabulation, which the sailor with the boyish face keeps out of. Then Chá Petro obviously gets his way; he stands on the prow and assumes his javelin-throwing stance, having swapped the harpoon for a weapon of the same size but with an extremely sharp head in an elongated heart shape, like a halberd. Carlos Eugénio moves forward with the engine on minimum, and the boat starts over to where the whale is breathing, immobile in a pool of blood, restless tail spasmodically slapping the water. This time the deadly weapon is thrown downwards; hurled on a slant, it penetrates the soft flesh as if it were butter. A dive: the great mass disappears, writhing underwater. Then the tail appears again, powerless, pitiful, like a black sail. And finally the huge head emerges and I hear the deathcry, a sharp wail, almost a whistle, shrill, agonizing, unbearable.

Читать дальше