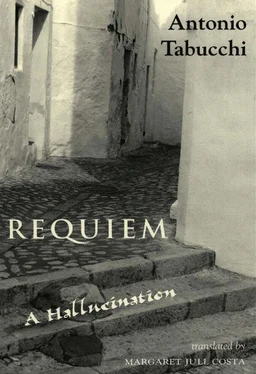

Antonio Tabucchi

Requiem: A Hallucination

THIS STORY, which takes place on a Sunday in July in a hot, deserted Lisbon, is the Requiem that the character I refer to as “I” was called on to perform in this book. Were someone to ask me why I wrote this story in Portuguese, I would answer simply that a story like this could only be written in Portuguese; it’s as simple as that. But there is something else that needs explaining. Strictly speaking, a Requiem should be written in Latin, at least that’s what tradition prescribes. Unfortunately, I don’t think I’d be up to it in Latin. I realised though that I couldn’t write a Requiem in my own language and that I required a different language, one that was for me a place of affection and reflection.

Besides being a “sonata”, this Requiem is also a dream, during which my character will meet both the living and the dead on equal terms: people, things and places that were, perhaps, in need of a prayer, a prayer that my character can only express in his own way, through a novel. But this book is, above all, a homage to a country I adopted and which, in turn, adopted me, to a people who liked me as much as I liked them.

Should anyone remark that this Requiem was not performed with due solemnity, I cannot but agree. But the fact is that I chose to play my music not on an organ, which is an instrument proper to cathedrals, but on a mouth-organ that you can carry about in your pocket, or on a barrel-organ that you can wheel through the streets. Like Carlos Drummond de Andrade, I’ve always had a fondness for street music and I agree with him when he says: “I have no desire to be friends with Handel, I’ve never heard the dawn chorus of the archangels. I’m happy with the noises that drift up from the street, which bear no message and are lost, just as we are lost.”

A.T.

THE CHARACTERS

ENCOUNTERED IN THIS BOOK

The Young Junky

The Lame Lottery-Ticket Seller

The Taxi Driver

The Waiter at the Brasileira

The Old Gypsy Woman

The Cemetery Keeper

Tadeus

Senhor Casimiro

Senhor Casimiro’s Wife

The Porter at the Pensão Isadora

Isadora

Viriata

My Father as a Young Man

The Barman at the Museum of Ancient Art

The Copyist

The Ticket Collector

The Lighthousekeeper’s Wife

The Manager of the Casa do Alentejo

Isabel

The Seller of Stories

Mariazinha

My Guest

The Accordionist

I

I THOUGHT: the guy isn’t going to turn up. And then I thought: I can’t call him a “guy,” he’s a great poet, perhaps the greatest poet of the twentieth century, he died years ago, I should treat him with respect or, at least, with deference. Meanwhile, however, I was beginning to get fed up. The Late July sun was blazing down and I thought: Here I am on holiday, I was having a really nice time at my friends’ house in the country in Azeitão, so why did I agree to this meeting here on the quayside? it’s utterly absurd. And, at my feet, I glimpsed the silhouette of my shadow and that seemed absurd to me too, incongruous, senseless; it was a brief shadow, crushed by the midday sun, and it was then that I remembered: He said twelve o’clock, but perhaps he meant twelve o’clock at night, because that’s when ghosts appear, at midnight. I got up and walked along the quayside. The traffic along the avenue had almost stopped, only a few cars passed now, some with sunshades on their roof-racks, people going to the beaches at Caparica, it was after all a sweltering hot day. I thought: What am I doing here in Lisbon on the last Sunday in July? and I started walking faster in order to reach Santos as quickly as possible, it might be a little cooler in the small park there.” The park was deserted, apart from the man at the newspaper stand. I went over to him and the man smiled. Have you read the news? he asked cheerily, Benfica won. I shook my head, no, I hadn’t seen the news yet, and the man said: it was an evening game in Spain, a benefit match. I bought the sports paper, A Bola , and chose a bench to sit down on. I was reading about the shot that had given Benfica the winning goal against Real Madrid, when I heard someone say: Good afternoon, and I looked up. Good afternoon, repeated the unshaven youth standing in front of me, I need your help. Help? For what? I asked. Food, he said, I haven’t eaten for two days. He was a young man in his twenties, wearing jeans and a shirt, and was timidly holding out his hand to me, as if asking for alms. He was blond and had bags under his eyes. You mean you haven’t had a fix for two days, I said instinctively, and the young man replied: it comes to the same thing, drugs are food too, at least for me they are. In theory, I’m in favour of all drugs, I said, soft and hard, but only in theory, in practice I’m against them, I’m afraid I’m one of those bourgeois intellectuals full of prejudices and I don’t think it’s right that you should take drugs in a public park, that you should make such a distressing spectacle of your body, I’m sorry, but it’s against my principles, I might be able to accept you taking drugs in the privacy of your own home, as people used to do, in the company of intelligent and cultivated friends, listening to Mozart or Erik Satie. By the way, I added, do you like Erik Satie? The Young Junky looked at me in surprise. Is he a friend of yours? he asked. No, I said, he’s a French composer, he was part of the avant-garde movement, a great composer from the age of surrealism, if one can speak of surrealism as belonging to an age, he wrote mostly for the piano, a deeply neurotic man I believe, like you and me perhaps, I’d like to have known him but we were born into different ages. Just two hundred escudos , said the Young Junky, two hundred escudos is all I need, I’ve got the rest of the money, Camarão will be along in half an hour, he’s the dealer, I need another fix, I’m getting withdrawal symptoms. The Young Junky took a handkerchief out of his pocket and blew his nose loudly. He had tears in his eyes. You’re not being fair, he said, I could have been aggressive, I could have threatened you, I could have played the hardened addict, but no, I was friendly, pleasant, we even chatted about music, and you still won’t give me two hundred escudos , it’s incredible. He blew his nose again and went on: Besides, the one hundred escudo notes are cool, they’ve got a picture of Fernando Pessoa on them, and now let me ask you a question, do you like Pessoa? Very much, I replied, I could even tell you a good story about him, but it’s not worth it, I feel a bit strange, I’ve just come from the Cais de Alcântara, but there was no one there, and I intend going back there at midnight, do you understand? No, I don’t, said the Young Junky, but it doesn’t matter, and thanks. He slipped the two hundred escudos I was holding out to him into his pocket, then blew his nose again. Right, he said, if you’ll excuse me, I have to go and look for Camarão now, I’m sorry, I really enjoyed talking to you, have a nice day, goodbye.

I leaned back on the bench and closed my eyes. It was horribly hot, I didn’t feel like reading A Bola any more, maybe it was hunger, but I couldn’t really be bothered to get up and go off in search of a restaurant, I preferred to stay there, in the shade, barely breathing.

It’s the big draw tomorrow, said a voice, wouldn’t you like to buy a lottery ticket? I opened my eyes. The voice belonged to a small man in his seventies, who was dressed modestly but bore on his face and in his manner the traces of a former dignity.

Читать дальше