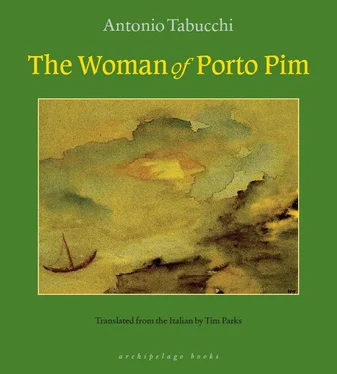

Antonio Tabucchi

The Woman of Porto Pim

I am very fond of honest travel books and have always read plenty of them. They have the virtue of bringing an elsewhere, at once theoretical and plausible, to our inescapable, unyielding here. Yet an elementary sense of loyalty obliges me to put any reader who imagines that this little book contains a travel diary on his or her guard. The travel diary requires either a flair for on-the-spot writing or a memory untainted by the imagination that memory itself generates — qualities which, out of a paradoxical sense of realism, I have given up any hope of acquiring. Having reached an age at which it seems more dignified to cultivate illusions than foolish aspirations, I have resigned myself to the destiny of writing after my own fashion.

Having said this, it would nevertheless be dishonest to pass these pages off as pure fiction: the friendly, I might almost say pocket-size muse that dictated them could not even remotely be compared with the majestic muse of Raymond Roussel, who managed to write his Impressions d’Afrique without ever stepping off his yacht. I did step off and put my feet on the ground, so that as well as being the product of my readiness to tell untruths, this little book partly has its origins in the time I spent in the Azores. Basically, its subject matter is the whale, an animal which more than any other would seem to be a metaphor; and shipwrecks, which insofar as they are understood as failures and inconclusive adventures, would likewise appear to be metaphorical. My respect for the imaginations which conjured up Jonah and Captain Ahab has luckily saved me from any attempt to sneak myself, via literature, in amongst the ghosts and myths that inhabit our imaginations. If I talk about whales and shipwrecks, it is merely because in the Azores such phenomena can boast an unequivocal reality. There are however two stories in this small volume which it would not be entirely inappropriate to define as fiction. The first, in its basic outline, is the life of Antero de Quental, that great and unhappy poet who measured the depths of the universe and the human spirit within the brief compass of the sonnet. I owe to Octavio Paz’s suggestion that poets have no biography and that their work is their biography, the idea of writing this story as if its subject were a fictional character. And then lives lost by the wayside, like Antero’s, perhaps hold up better than others to being told along the lines of the hypothetical. The story which closes the book, on the other hand, I owe to the confidences of a man whom I may be supposed to have met in a tavern in Porto Pim. I won’t rule out my having altered it with the kind of additions and motives typical of one who believes that he can draw out the sense of a life just by telling its story. Perhaps it will be considered an extenuating circumstance if I confess that alcoholic beverages were consumed in abundance in this tavern and that I felt it would have been impolite of me not to participate in the locally recognised custom.

The fragment of a story entitled “Small Blue Whales Strolling about the Azores” can be thought of as guided fiction, in the sense that it was prompted by a snatch of conversation overheard by chance. I don’t even know myself what had happened before and what afterwards. I presume it is about a kind of shipwreck, which is why I put it in the chapter where it is.

The piece entitled “A Dream in Letter Form” I owe partly to reading Plato and partly to the rolling motion of a slow bus from Horta to Almoxarife. It may be that in the transition from dream to text the content has suffered some distortions, but each of us has the right to treat his dreams as he thinks fit. On the other hand the pages entitled “High Seas” aspire to no more than a factual account, the only merit they can claim being their trustworthiness. Similarly many other pages, and I feel it would be superfluous to say which, are mere transcripts of the real or of what others have written before me. Finally, the piece entitled “A Whale’s View of Man,” in addition to my old vice of looking at things from another’s point of view, unashamedly takes its inspiration from a poem by Carlos Drummond de Andrade, who, before myself, and better than myself, chose to see mankind through the sorrowful eyes of a slow animal. And it is to Drummond that this piece is humbly dedicated, partly in memory of an afternoon in Plinio Doyle’s house in Ipanema when he told me about his childhood and about Halley’s comet.

Vecchiano, 23 September 1982

Having sailed for many days and many nights, I realized that the West has no end, but moves along with us, we can follow it as long as we like without ever reaching it. Such is the unknown sea beyond the Pillars, endless and always the same, and it is from that sea, like the thin backbone of an extinct colossus, that these small island crests rise up, knots of rock lost in the blue.

Seen from the sea, the first island you come to is a green expanse amidst which fruit gleams like gems, though sometimes what you may be seeing are strange birds with purple plumage. The coastline is impervious, black rock-faces inhabited by marauding sea birds which wail as twilight falls, flapping restlessly with an air of sinister torment. Rains are heavy and the sun pitiless: and because of this climate together with the island’s rich black soil, the trees are extremely tall, the woods luxuriant and flowers abound, great blue and pink flowers, fleshy as fruit, such as I have never seen anywhere else. The other islands are rockier, though always rich in flowers and fruit, and the inhabitants get much of their food from the woods, and then the rest from the sea, since the water is warm and teeming with fish.

The men have light complexions and astonished eyes, as if the wonder at a sight once seen but now forgotten still played across their faces. They are silent and solitary but not sad and they will frequently laugh over nothing, like children. The women are handsome and proud, with prominent cheekbones and high foreheads. They walk with waterjugs on their heads, and descending the steep flights of steps that lead to the water their bodies don’t sway at all, so that they look like statues on which some god has bestowed the gift of movement. These people have no king, they know nothing of class or caste. There are no warriors because they have no need to wage war, having no neighbors. They do have priests, though of a special kind which I will tell you about later on. And anybody can become one, even the humblest peasant or beggar. Their Pantheon is not made up of gods like ours who preside over the sky, the earth, the sea, the underworld, the woods, the harvest, war and peace and the affairs of mankind. Instead they are gods of the spirit, of sentiments and passions. The principal deities are nine in number, like the islands in the archipelago, and each has his temple on a different island.

The god of Regret and Nostalgia is a child with an old man’s face. His temple stands on the remotest of the islands in a valley protected by impenetrable mountains, near a lake, in a desolate, wild stretch of country. The valley is forever covered by a light mist, like a veil; there are tall beech trees which whisper in the breeze; a place of intense melancholy. To reach the temple you have to follow a path cut into the rock like the bed of a dried stream. And as you walk you come across strange skeletons of enormous unknown animals, fish perhaps, or maybe birds; and seashells, and stones the pink of mother-of-pearl. I called it a temple, but I ought to have said a shack: for the god of Regret and Nostalgia could hardly live in a palace or luxurious villa; instead he has but a hovel, poor as wept tears, something that stands amidst the things of this world with that same sense of shame as some secret sorrow lurking in our hearts. For this god is not only the god of Regret and Nostalgia; his deity extends to an area of the mind that includes remorse, and the sorrow for that which once was and which no longer causes sorrow but only the memory of sorrow, and the sorrow for that which never was but should have been, which is the most consuming sorrow of all. Men go to visit him dressed in wretched sackcloth, women cover themselves with dark cloaks; and they all stand in silence and sometimes you hear weeping, in the night, as the moon casts its silver light over the valley and over the pilgrims stretched out on the grass nursing their lifetime’s regrets.

Читать дальше