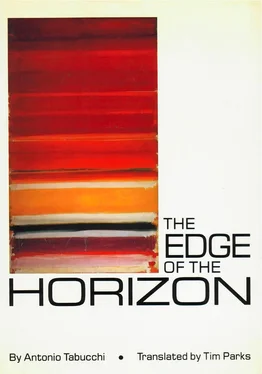

Antonio Tabucchi

The Edge of the Horizon

“Having been” belongs in some way to

a “third kind,” radically heterogeneous to both

being and non-being.

— VLADIMIR JANKELEVITCH

To open the drawers you have to turn the handle and press down. This disconnects the spring, the mechanism is set off with a slight metallic click, and the ball bearings automatically begin to slide. The drawers are stacked at a slight angle and run out of their own accord on small rails. First you see the feet, then the stomach, then the chest, then the head of the corpse. Sometimes, when an autopsy hasn’t been performed, you have to help the mechanism by pulling the drawer with your hands, since some of the corpses will have bloated stomachs which press against the drawer above and so get stuck. The corpses which have been autopsied on the other hand are dry, as though drained, with a sort of zip fastener along their stomachs and their innards stuffed with sawdust. They make you think of big dolls, oversized puppets from a show whose run has ended, tossed away in a store for old bric-a-brac. And in a way this is life’s storehouse. Before their final disappearance, the discarded products of the scene find a last home here while waiting for suitable classification, since the causes of their deaths cannot be left in doubt. That’s why they are lying here, and he looks after them and watches over them. He manages the anteroom that leads to the definitive disappearance of their visible image; he records their entry and their departure; he classifies them; he numbers them; sometimes he photographs them; he fills in the file-card that will allow them to vanish from the world of the senses; he hands out their final ticket. He is their last companion, and something more, like a posthumous guardian, impassive and objective.

Then is the distance that separates the living from the dead, he sometimes wonders, really so great? He’s unable to answer his own question. In any event cohabitation, if we can call it that, helps to reduce that distance. The corpses have to have a little card attached to their big toes with a registration number, but he’s sure that, in the remote way in which they are present, they detest being classified with a number as if they were objects. Because of this, when he thinks about them himself he gives them jokey nicknames, some entirely random, others suggested by a vague likeness to, or circumstance in common with, some character in an old film: Mae West, Professor Unrat, Marcelino Pan y Vino. Pablito Calvo, for example, is the exact double of Marcelino: round face, knobbly knees, a short shiny black fringe. Thirteen years old, Pablito was working illegally when he fell off some scaffolding. The father can’t be found, the mother lives in Sardinia and can’t come. They’ll be sending him back to her tomorrow.

Of the original hospital, only the temporary reception ward and the morgue are still here in this old part of town, otherwise referred to as the historic center. For a long time now this area has been considered a site for study and restoration. But the years go by, local governments alternate, vested interests change and the part to be restored grows more and more decrepit. And then the city encroaches menacingly from other areas, drawing the attention of the experts elsewhere, to suburbs where the “productive” population is ever more densely settled, where huge dormitories have been built. It’s the buildings in these areas that demand the time of the municipal engineers. Sometimes the hillside will slip, as if it wanted to shrug off those ugly encrustations — and urgent measures are introduced, special funds made available. Then there are roads to be built, sewers and gas pipes to be linked up, schools, nurseries, clinics. Here in the center, on the other hand, the agony is diffuse, a slow leprosy that has invaded walls and houses whose decay is stealthy and irreversible, like a pending death sentence. Here live pensioners, prostitutes, street vendors, fishmongers, unemployed young layabouts, grocers with ancient, damp, dark shops that smell of spices and dried cod, above whose doors one can barely make out faded signs announcing: “Wines — Colonial Products — Tobaccos.” The garbage men rarely come by; even they disdain the leavings of this second-class humanity. In the evening syringes glitter in the narrow streets, there are plastic bags, and sometimes the shapeless mass of a rat dead in a corner where a phosphorescent poster put up by the Pest Control Department warns you not to touch the verdigris-colored bait scattered on the ground.

Sara has frequently said she’d like to come and pick him up on those evenings his shift finishes at ten, but he has always forbidden her. Not so much for fear of the people; in the evening the narrow street is home for three quiet prostitutes who have watchful pimps at first-floor windows. No, what worries him most are the bands of rats that roam around aggressively in the evening. Sara has no idea how big they are; he’s sure she would be terrified; she can’t imagine what they’re like. True, the city abounds in rats, but this area has its own special breed. Spino has a theory, but he’s never told anyone, least of all Sara. He thinks it’s the morgue that attracts them.

Saturday evenings they usually go to the Magic Lantern. It’s a film club at the top of Vico dei Carbonari in a small courtyard that looks like some corner of a country village and reminds you of farmhouses, patches of countryside, times past. From up here you can see the harbor, the open sea, the tangle of tiny streets in the old Jewish ghetto, the pinkish bell tower of a church hemmed in between walls and houses, invisible from other parts of the city, unsuspected. You have to climb a brick stairway worn by long use, a long shiny iron bar serving as a handrail, twisting along a pitted wall invaded by tufts of caper plants obscuring faded graffiti. You can still read: “Long live Coppi” and “The exploiters’ law shall not pass.” Things from years gone by. On summer nights, after the film, they wind up their evening in a small café at the end of the narrow street where two blocks of granite with a chain between them mark off a little terrace complete with pergola and surrounded by a shaky wall. There are four small tables with green iron legs and marble tops where the circles of wine and coffee the stone has absorbed and made its own trace out hieroglyphics, little patterns to interpret, the archaeology of a recent past of other customers, other evenings, drinking bouts perhaps, late nights with card games and singing.

Beneath them the untidy geometry of the city falls sheer away together with the lights of villages along the bay, the world. Sara has a mint granita that they still make here using a primitive little gadget. With a grater fitted inside a small aluminum box, it scrapes the fragments of ice together compact and soft as snow. The proprietor is a fat man with bags under his eyes and a lazy walk. He wears a white apron that emphasizes his paunch, he smiles, he pronounces his always miserable weather predictions: “Tomorrow it’ll get colder, the wind is from the east” or “This haze’ll bring rain.” He prides himself on knowing the winds and weather; he was a seaman when he was younger; he worked on a steamship on the Americas route.

Even when it’s hot Sara draws in her legs and covers her shoulders with a shawl, since the night air gives her pains in her joints.

Читать дальше