Rachel Carson

THE EDGE OF THE SEA

with illustrations by Bob Hines

and a new introduction by Sue Hubbell

To Dorothy and Stanley Freeman

who have gone down with me into the low-tide world

and have felt its beauty and its mystery.

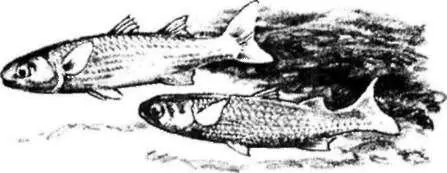

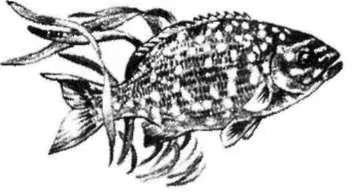

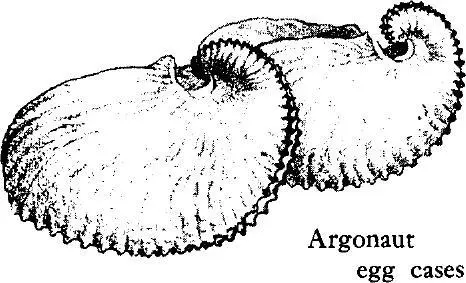

OUR UNDERSTANDING of the nature of the shore and of the lives of sea animals has been acquired through the labor of many hundreds of people, some of whom have devoted a lifetime to the study of a single group of animals. In my researches for this book I have been deeply conscious of the debt of gratitude we owe these men and women, whose toil allows us to sense the wholeness of life as it is lived by many of the creatures of the shore. I am even more immediately aware of my debt to those I have consulted personally, comparing observations, seeking advice and information and always finding it freely and generously given. It is impossible to express my thanks to all these people by name, but a few must have special mention. Several members of the staff of the United States National Museum have not only settled many of my questions but have given invaluable advice and assistance to Bob Hines in his preparation of the drawings. For this help we are especially grateful to R. Tucker Abbott, Frederick M. Bayer, Fenner Chace, the late Austin H. Clark, Harald Rehder, and Leonard Schultz. Dr. W. N. Bradley of the United States Geological Survey has been my friendly advisor on geological matters, answering many questions and critically reading portions of the manuscript. Professor William Randolph Taylor of the University of Michigan has responded instantly and cheerfully to my calls for aid in identifying marine algae, and Professor and Mrs. T. A. Stephenson of the University College of Wales, whose work on the ecology of the shore has been especially stimulating, have advised and encouraged me in correspondence. To Professor Henry B. Bigelow of Harvard University I am everlastingly in debt for encouragement and friendly counsel over many years. The grant of a Guggenheim Fellowship helped finance the first year of study in which the foundations of this book were laid, and some of the field work that has taken me along the tide lines from Maine to Florida.

LIKE THE SEA ITSELF, the shore fascinates us who return to it, the place of our dim ancestral beginnings. In the recurrent rhythms of tides and surf and in the varied life of the tide lines there is the obvious attraction of movement and change and beauty. There is also, I am convinced, a deeper fascination born of inner meaning and significance.

When we go down to the low-tide line, we enter a world that is as old as the earth itself—the primeval meeting place of the elements of earth and water, a place of compromise and conflict and eternal change. For us as living creatures it has special meaning as an area in or near which some entity that could be distinguished as Life first drifted in shallow waters-reproducing, evolving, yielding that endlessly varied stream of living things that has surged through time and space to occupy the earth.

To understand the shore, it is not enough to catalogue its life. Understanding comes only when, standing on a beach, we can sense the long rhythms of earth and sea that sculptured its land forms and produced the rock and sand of which it is composed; when we can sense with the eye and ear of the mind the surge of life beating always at its shores—blindly, inexorably pressing for a foothold. To understand the life of the shore, it is not enough to pick up an empty shell and say “This is a murex,” or “That is an angel wing.” True understanding demands intuitive comprehension of the whole life of the creature that once inhabited this empty shell: how it survived amid surf and storms, what were its enemies, how it found food and reproduced its kind, what were its relations to the particular sea world in which it lived.

The seashores of the world may be divided into three basic types: the rugged shores of rock, the sand beaches, and the coral reefs and all their associated features. Each has its typical community of plants and animals. The Atlantic coast of the United States is one of the few in the world that provide clear examples of each of these types. I have chosen it as the setting for my pictures of shore life, although—such is the universality of the sea world—the broad outlines of the pictures might apply-on many shores of the earth.

I have tried to interpret the shore in terms of that essential unity that binds life to the earth. In Chapter I, in a series of recollections of places that have stirred me deeply, I have expressed some of the thoughts and feelings that make the sea’s edge, for me, a place of exceeding beauty and fascination. Chapter II introduces as basic themes the sea forces that will recur again and again throughout the book as molding and determining the life of the shore: surf, currents, tides, the very waters of the sea. Chapters III, IV, and V are interpretations, respectively, of a rocky coast, the sand beaches, and the world of the coral reefs.

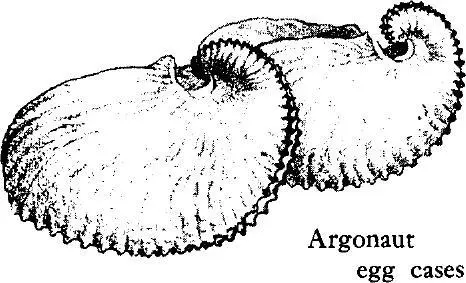

The drawings by Bob Hines have been provided in abundance so the reader may gain a sense of familiarity with the creatures that move through these pages, and may also be helped to recognize those he meets in his own explorations of the shore. For the convenience of those who like to pigeonhole their findings neatly in the classification schemes the human mind has devised, an appendix presents the conventional groups, or phyla, of plants and animals and describes typical examples. Each form mentioned in the book itself is listed under its Latin as well as its common name in the index.

RACHEL CARSON died in the springtime of 1964, a woman of only fifty-six years, with an established literary reputation and fame, too. She had written four books by that time, all excellent in varying ways and every one a bestseller.

Silent Spring, with its revelations about pesticides and their effects on the natural world, had been the most recent, published less than two years before cancer and its complications took her life. Its popularity with the general reading public—the right book at the right time—made her a pioneer of what we now call environmentalism. This reputation has made a great many people forget that Rachel Carson was first and foremost a writer of considerable literary style whose true love was the sea.

She was, by training, a marine zoologist, and her books before Silent Spring all had been about one aspect or another of the oceans. Part of the reason Silent Spring came to be such a success was that those previous books had established her name. Nevertheless, today her books on the sea seem to be all but forgotten, which is a shame, since in many ways a book such as The Edge of the Sea is more approachable, better written, and more relevant today than the monumental but now somewhat dated Silent Spring.

Читать дальше