Today it is overhead

The mainmast pierces the palm of this hand, hurting it

The way my sliced-off hand hurts me, pierced by a continual sting

Cendrars becomes the hermit of Aix-en-Province, where he lives quietly from 1940 on. His children are at the front, his lover, Raymone, in Brazil with Louis Jouvet’s theater troupe. The poet has stopped writing, he kills time in country inns, curses the Krauts from bars along the Cours Mirabeau, scours the shelves of the Méjanes Library, and, in a large apartment on the rue Clémenceau, watches over “Mamanternelle,” the eighty-four-year-old mother of his forever lover. Three years of silence, three years before the demon of writing, drowned by France’s defeat, again dictates its law to him, the text will become The Astonished Man . Others follow, he writes about the Last Judgment, about the patron saint of aviation, Saint Joseph of Cupertino, an ace at levitation. Raymone has come home. Nearby, Laurin, another one-armed man, sabotages German trains; farther off in Céreste, René Char, another poet, aka Captain Alexandre, takes to the hills with the maquis. Following the Liberation, in October 1945, a young reporter by the name of Robert Doisneau photographs Blaise under an arbor in the garden, behind the cactuses and tall grasses, in shirtsleeves, a beret planted on his head and a cigarette screwed into the corner of his mouth. He is no longer the dandy in shabby clothes painted by Modigliani, but a grandfather, back from a thousand battles, wiser, living in exile, his creased face enlivened by half-shut eyes. At his worktable, the typewriter on one side, the glass and rum bottle on the other. Blaise ages, and the young come running. They visit Aix as if performing a pilgrimage. It tickles him.

Hard on the heels of Robert Doisneau comes René Fallet, just demobilized: “Monsieur Cendrars, you are fifty-six, I am eighteen, and you could be, as they say, my father, but I recognize you, celebrate you, love you …” he writes. Not a father but a brother, a friendly hand to join in scouring bistro counters, breaking glasses at the Deux Garçons, talking poetry, chameleons, birds, lilies, betting your life on a coin toss — someone to team up with. Words of sweet friendship. A disciple without discipline. The hermit of Saint-Victoire levies an army of lads with a wave of his friendly hand.

A young man, another, his son not by adoption but by blood, the pilot Rémy Sauser, dies while flying beyond the Mediterranean in Morocco. A dull pain, stunning, “a punch in the face,” Blaise says to a friend. He finishes The Bloody Hand , writes by way of epigraph: “FOR MY SONS ODILON AND RÉMY WHEN THEY RETURN FROM WAR AND CAPTIVITY AND FOR THEIR SONS WHEN THOSE SONS TURN TWENTY ALAS!..” then adds a new paragraph as a postscript, as if it were a last message, telegraphing his pain:

Alas!.. On November 26, 1945, a cable from Meknes (Morocco) informs me that Rémy was killed in an airplane accident. Poor Rémy, so happy to be flying over the Atlas Mountains every morning, so happy to be alive since returning from captivity in Krautland. It’s too sad … But one of the privileges of this dangerous calling of fighter pilot is that you can be killed in mid-flight and die young. My son rests, among his similarly fallen comrades, in the small and already overpopulated square of sand in the Meknes cemetery reserved for airmen, each folded into his parachute, like mummies or larvae, waiting among the infidels, poor kids, for the sun of resurrection .

And Raymone, separated, found again, mourns Rémy as her son, her favorite. Once more acting in the theater in Paris, she writes Blaise: “I was sure I would never see Rémy again. When he kissed me, at the metro, he felt that my eyes were saying farewell, and he came back and clasped my hands …” The phantom limb syndrome of the amputee, the son forever linked to the body, hallucinosis, a pathology of the stump, Rémy comes back to haunt his father in a “last little postcard,” sent on November 4, 1945: “Dear Blaise, My work is getting more and more interesting, and I’m delighted. Everything is great, my work, the weather, the grub (dates, oranges, and tangerines) and I hope to stay here until Easter, return to France in spring. I hope that everything is OK on your side too. Kisses. Rémy.”

A monoplane lost in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

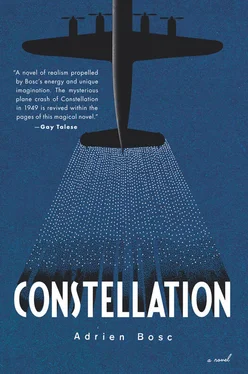

A Lockheed Constellation vaporized in the middle of the Atlantic.

When you love, you come back. A life of breaking the compass, opening up to the cardinal points, and then, at the far end of the world, discovering the commonplace. When you love, you come back. A life of playing hide-and-seek, cheating boredom, cheating death, and, at the far threshold, the old cabin, the origin, the treasure. When you love, you come back. Reviled, despairing, in a jumble, the mind gaudy with strange animals and utopian landscapes, to discover in the depths of the primeval forest a patient, protective sister soul. When you love, you come back. A life that leaves you breathless, Russia, eastern China, Panamanian uncles, the Amazon, whales off Tierra del Fuego, Amsterdam, Antwerp, the horizon declining at the equator, war and ships, a whole life under the sign of departure. Of arrival, an unexpected, a banal arrival, from right next door, and the Odyssey as a great detour. When you love, you come back. On October 27, 1949, at Sigriswil, in the Bernese Oberland, while a plane bearing the name Constellation takes off from Orly, the poet Blaise Cendrars marries the woman he has loved forever, Raymone Duchateau. The marriage of old lovers in a Swiss-German inn, first the engagement trip, the ring seals his return to his country of birth. Blaise, the stateless one, has found a state. Having left never to return, he finds in the village of Sigriswil, at the threshold of his life, the land of his ancestors. And he, a Swiss in flight afraid of never arriving, when finally Raymone agrees to marry, finds his Ithaca in the faces of the peasants from the Oberland. In its history, its expressions, its noses, he recognizes intangible signs of his ancestry. In the genealogy of the winemakers of Lake Thun, a shared character, a brotherhood of the untamed, the rebelled. In the drawing room of the inn, partying with friends after the wedding, Blaise announces that he is writing a Conquest of Sigriswil . Nothing will come of it. In the small ninth-century church, looking at a painting on wood, he recognizes his forebears among the thirty solid bourgeois on the altarpiece; on October 27, 1949, at the moment when the Constellation is taking off at Orly, the separated but inseparable lovers join, the poet with the missing hand arrives at safe haven.

In 1956, Blaise Cendrars publishes his last novel, Take Me to the End of the World! The title is a call in counterfeit form, no exoticism, no fantasized travel account, but a man’s truth. The end of the world, as a planet makes its revolution, is not far off. From the threshold , an initial, limiting value, the foot of a doorway marked by stone or wood, or else a term from the vocabulary of aviation, displaced threshold , near the beginning and end of a runway. He gives his testament, while the fantastic, the dream element in the shape of an endpoint, is here in Paris: “The end of the world is the Père-Lachaise cemetery.”

On the ground floor of the apartment on the rue José-Maria-de-Heredia, Blaise Cendrars dies. Paralyzed, he lives through an endless, monthlong agony. On January 21, 1961, Raymone closes her husband’s eyelids, Miriam holds her father’s hand. Don’t smile through your tears.

Читать дальше