It’s at a depth of 35 meters. Twenty-five cubic meters every twenty-four hours. At 160 meters’ depth, it’s 250 cubic meters. But I’ve had it up to here with those villagers from Másklina. I’m not going to let them in on this. Unless they pay me. If they don’t, then let the water lie.

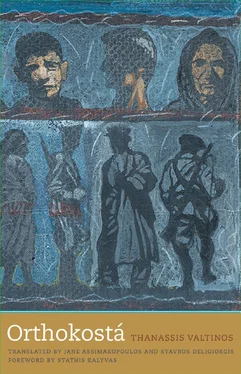

The Orthokostá Monastery is situated on the eastern foothills of Mount Parnon (locally known as Malevós), precisely on the road — until recently a mule path and at present a paved motorway — connecting the Ayios Andréas and the Prastós communities, both belonging to the wider Tsakoniá (southern Kynouría) region. The exact coordinates for the monastery (page titled: Dresthená-Asómatoi, sc. 1:50,000, Army Geographical Service, 1938) are K + 290838, and its earliest archaeological remains date back to the times of the Iconomachy . 1 It is dedicated to the Dormition of the Virgin, and its feast is celebrated on August 23 (the Ninth-day Feast), the meaning of the name Orthokostá being unknown to this day. One possible derivation is the mispronunciation of the Tsakónikan place name Órto-Kótsa (the hill on whose northeastern slope it stands). It lies above an impressively steep and narrow ravine, extending from north to south .

Isaákios’s mendacious assertions concerning the expansive alluvial plain of the river Mégas, the sea of Náfplion, and the bright-shining vein of silver and lead ought simply to be taken as the poetic escapism of a repressed existence. Isaákios, the bishop of Rhéon and Prastós (1730–1805), after being impeached by the Ecumenical Patriarchate for heretical beliefs and simony, spent the last twelve years of his life under a restraining order at the Orthokostá Monastery .

Thanassis Valtinos came onto the literary scene in Greece in the early 1960s with several novella-length prose narratives that heralded a marked shift away from the florid, discursive prose of the fiction of the times toward what was to become a much-imitated and highly respected style of documentary fiction marked by the sparse, unadorned speech of oral accounts. His early works, such as The Descent of the Nine (1963), The Life and Times of Andreas Kordopatis , Book 1: America (1964), and the later Deep Blue Almost Black (1985), are all relatively short first-person narratives that simulate the type of spontaneous communication usually heard among ordinary people.

In the 1990s Valtinos began combining similar first-person narratives with letters or documents into longer, polyphonic works and produced what are most certainly his three major works: Data from the Decade of the Sixties (1989), Orthokostá (1994), and The Life and Times of Andreas Kordopatis , Book 2: The Balkans ’22 (2000), to be followed again by shorter titles in the twenty-first century. Orthokostá can arguably be called the peak of Valtinos’s literary career, coming as it does midway between his other two major works. Indeed, its standing in the critical canon of Greece is undiminished today, more than twenty years since its publication.

The subject of Valtinos’s novels is not history itself but the recording of history, the way it is remembered and depicted, orally or in writing, reliably or not. What emerges from the seemingly unedited raw footage of his novels is a poignant re-living of history by its participants on a day-to-day basis, regardless of their social circumstances, level of education, or political orientation.

The numerous narrators, be they participants, victims, or innocent bystanders, recount in hindsight, and from many differing vantage points, the hardships and atrocities of the conflict portrayed in Orthokostá , such as the Communist guerrillas’ burning of Valtinos’s home village of Kastri and smaller villages like Ayia Sofia; their detaining of combatants and civilians alike in the monasteries of Orthokostá and Loukou and in local schools; the torture, forced marches, and executions of many of those detained, and the subsequent revenge killings by rightist and collaborationist Security Battalions. And while both sides engage in extensive looting and stealing, German troops are carrying out their own murderous “clean-up” operations in the region by arresting, torturing, and executing villagers while imposing consecutive blockades on the village of Kastri.

It is in the midst of such contrary tides that the human element begins to emerge. Although the narrators are not clearly identified initially, they gradually come into focus as their families and fortunes are pieced together through their own and others’ imperfect recollections of the decades-old events. Certain key incidents are told and retold throughout Orthokostá , each additional telling either contradicting an earlier account or shedding new light on the events in question.

In one of the closing chapters of the novel, at the prodding of an unnamed interlocutor, a surviving participant pulls together the different strands of the novel by recounting some of its central executions while also telling of his own travails at the hands first of the German occupying forces and then of the Communist guerrillas, as well as the horrific circumstances of his brother’s execution by the latter — the kind of account which today, in 2016, would immediately go viral on the Internet, but which in 1994, when Orthokostá was first published, was all the more shocking for having been repressed for fifty years as taboo subject matter.

In practical terms, Orthokostá is steeped in references to village customs and linguistic constructions which imbue the narratives with both local color and a sense of verisimilitude. In the original this is masterfully done through Valtinos’s frequent citing and trademark cataloguing of local-sounding names that impart an immediate ring of familiarity to the Greek text, as well as an unmistakable affinity with the epic tradition. To the English-speaking reader, however, Greek proper names are anything but familiar. We have resisted Anglicizing these names (Georgia for Yeorghía, for example) in the interest of preserving the Greekness at the core of Orthokostá . We have also tried to make the names and proper names less difficult to pronounce by accenting those that are not already familiar to English-speaking readers and by generally favoring a more phonetic spelling system than that dictated by tradition. Whether phonetic or traditional or a mix of both, individual names are consistently transliterated throughout the novel.

Names and naming, more so than expressions in a specific dialect, are in fact what often distinguishes local parlance in these and other peripheral regions from speech in mainland Greek cities. Whereas oral speech and dialogue are best rendered by equivalents rather than literal translations, names present their own set of problems. In Orthokostá , nicknames, diminutives, compound names, and first or last names with suffixes added are all cases in point. Suffixes added onto names in order to denote ownership (as in “Makréka,” meaning the house, houses, neighborhood, property, or land of the Makrís family) or relationship (as in “Sokrátaina,” meaning the wife, daughter, or mother of Sokrátis) are typical examples of this. We have dealt with these on a case-by-case basis, sometimes through free translation or interpretive interventions in the text itself and sometimes through explanatory notes.

From a grammatical point of view, and again in the interest of simplicity and intelligibility, the variously inflected forms of names of men and women in the Greek have been rendered in a rather unflattering masculine nominative singular that is currently the norm in English.

Читать дальше