— Before they arrested Panayótis.

— Before they arrested Panayótis. They arrested Panayótis instead of me.

— So they arrested you in 1943 then, in Astros.

— It couldn’t be 1943.

— It was ’43. And in February 1944 you were freed. How did they arrest you in Astros?

— How they arrested me?

— Yes.

— It was — I went to that fellow Kateriniós. The father of Níkos the fishmonger.

— Yes.

— Because I came back half-dead, I’d been shut in a cave without food for eight days. When the officers left. When we left Artemísion.

— Yes.

— I went to that cave, back toward Náfplion. I was tired and barefoot. I went to some house to get bread and had a quarrel. They were sleeping. I quarreled with them. And I got on the caïque to leave.

— To go where?

— To Náfplion. Kateriniós, God rest his soul. At any rate, he was with them. Hanging around with them.

— With the men from ELAS?

— Yes, I tell him. I tell Níkos the fishmonger’s father.

— Yes.

— I tell him, Take me to Náfplion. The caïque was at the far pier. And on the other side, at Koutrouyiórghis’s bakeshop, Pepónias and Vamprákos had set up a machine gun.

— I see.

— They fire a burst, and they tell the caïque to turn back. I tell him, Keep going, Kateriniós. Nothing doing. He turned round right there. Then they arrested me and took me to the detention camp. I threw my pistol in the sea. If I’d killed Kateriniós I’d have made it to Náfplion. I knew how to take the caïque there. But it never crossed my mind to kill him. Or to threaten him. I knew how to get the motor started. I’d have taken it there. Taken it to Náfplion. And my troubles would never have started.

— Pepónias and Vamprákos were the ones who arrested you.

— Vamprákos and Pepónias. And Kapetán Mavromantilás.

— Mavromantilás.

— Mihális. He was down there. Mavromantilás, Pepónias, and Vamprákos. And Kapetán Pávlos Bouziánis. From Mánesi. He had a brother-in-law in Trípolis, in Dalaína. Who was hanging around with the Italians. His daughters were. He had stolen lots of money from people. He was a big businessman, general foodstuffs. It was down there that they arrested me. They took me to the school in Meligoú. And in Meligoú they tied me up. Tied my feet — my knees and my ankles. And my hands. Kapetán Pávlos Bouziánis arrives and hits me with the butt of his rifle. I fall down, with half my teeth knocked out. I tell him, Why are you hitting me? He says, You’re a goddamn traitor. I say, Who did I betray? I went after the Italians, I fought them. You’re a traitor. Tell us what officers you were keeping company with. I say, I don’t know any officers, I don’t remember.

— On Mount Taygetus?

— Yes. The officers I kept company with. I don’t remember. You don’t remember? And then they gave it to me. They put the rifle through the ropes on my legs, and they turned my legs with the soles facing up. And they started. Thirty lashes with a metal cable.

— At the school in Meligoú.

— In Meligoú. From there they take me to Loukoú.

— Were there other men there?

— Lots of them. They killed a boy, Pátra’s boy. Pátra of all people. Such a well-respected lady. Cleopatra’s boy. He had a Martelli, a small bouzouki, and he used to play. He’d go begging, have himself a drink. And they killed him.

— In Loukoú?

— Outside Loukoú. They put me in the next day. I slept tied up in ropes. I slept on a board. We didn’t all fit in Loukoú. Nikoláou was there, Dránias was there.

— Yiánnis?

— Yiánnis. That son of a bitch Theóktistos was there. The deacon. He calls me a traitor and spits at me. Does the same to Astéris Papayiánnis’s sister. Ada. I spit on you, you traitoress. Why am I a traitor, Father? I only just now got back from Albania. At any rate. Then they made me dig my grave. In the yard of the monastery. In the corner. I dug it out with a pickax and a shovel.

— With your feet all swollen?

— My feet still swollen. Open and oozing. At any rate. They put me in, they throw me in there alive. Someone comes over.

— Who came over?

— Someone named Kíliaris. Thodorís Kíliaris. He worked for the Trípolis Electric Company. Down below, at the railroad tracks. Thodorís Kíliaris. And a man from some island. And Vasílis Tóyias from Mesorráhi. They threw me in, they buried me up to my neck. Will you become a rebel? No. Why not, you traitor? And then he hits me with his rifle butt right here, and knocks out the rest of my teeth. My lips were all cut up.

— Kíliaris?

— Tóyias. He hit me with his rifle butt, while I was half-buried. He hit me right here. That was it. They got me out. They gave me a good thrashing. With that metal cable. On my sides, on my kidneys. It was thick. They made it into a club. My skin welted up, they beat me black and blue. Nikoláou and Hasánis, God rest his soul. They tell me, Be patient, Iraklís. Those bastards, they wouldn’t just shoot me. I tell Tóyias, Why don’t you shoot me, why are you torturing me? What have I done to you? I won’t become a rebel. That’s it. They take us, and we go to Karakovoúni.

— From Loukoú.

— From Loukoú. On my knees most of the way. So we went up there. Yiánnis Vasílimis was there. The brother of Kapetán Vasílimis, Kóstas’s brother. And Aristídis. The one who went crazy and died recently. And Lykoúrgos. The father of Yiórghis Vasílimis, who had the stables over in Koúvli, with the calves. Yiánnis’s wife Miliá came there. She brought her husband squash patties. But me, they wouldn’t let me eat.

— What month was that?

— Now it was winter. In February I was freed. Twenty centimeters of snow outside. They had me cutting wood in my bare feet. But no, I couldn’t eat. Keep going, Yiánnis tells me, take my army coat and put it on. Inside his coat he had four patties, squash patties. Vasílimis. I ate them, like medicine. Someone saw me do that, he starts yelling. Hey, you, what were you eating? I say, Nothing. What did you hide in your pocket and eat? I didn’t hide anything. And so a few days later Nikitákis arrives, Dimítris Nikitákis himself, a dairy farmer from Sparta. He brings about sixty prisoners with him. All from Laconía. He brings them, and they join the two detention camps. Ours was under the command of Kapetán Kléarhos Aryiríou. Under his administration.

— Kléarhos was there?

— Of course.

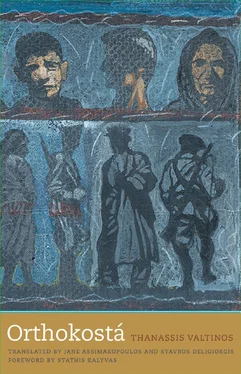

— Now you were all in Orthokostá.

— In Orthokostá. They beat me again there. A lot. Mítsos Nikitákis calls me. The dairy farmer. Who later on had a shop in Ayía Paraskeví, at the main intersection. In Athens. Mítsos’s story is very long. He escaped from a group of men the Germans shot in Monodéndri, and he went and joined the rebels. With two twelve-year-old children and his wife. He had his children with him. But he was a good man. A very good man. And he’s the one that helped us escape from Mávri Trýpa. We were slow getting out, the Germans arrived, we couldn’t get away in time, there was an order to execute us. He got us out.

— So Nikitákis calls you over.

— Yes. He tells me, Come here. Are you hungry? I am. He gives me a piece of pork. A thick piece. Do you have cigarettes? I didn’t have any. Money? I had a little money. He went and brought me cigarettes. Then he tells me. Or rather he told them, Don’t beat this prisoner any more. And he asked me why I wouldn’t join. I tell him, It’s like this. What could I say to him? Where you from? From Kastrí, Kynouría. Don’t beat this prisoner again. If anyone lays a hand on you, you tell me. All right. What could I do, as soon as he left they’d beat me senseless. They’d already done the worst torture on me. And they’d just finish me off. Like when they locked me in the monastery. Lying on a big table. My feet were bound and freezing underneath. And they had a fire and nails and they’d burn them.

Читать дальше