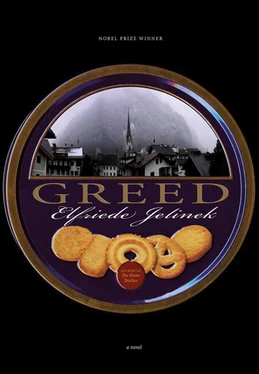

Elfriede Jelinek - Greed

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Elfriede Jelinek - Greed» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Greed

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Greed: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Greed»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

For anyone who wants to write or read daredevil, risk-taking prose, therefore, it was tremendously encouraging that Elfriede Jelinek won the Nobel prize for literature in 2004. But most British readers hadn't heard of her, despite four novels being available from Serpent's Tail (Lust, Wonderful, Wonderful Times, Women as Lovers, and The Piano Teacher), all of them full of her uniquely sneering tone and tireless fury with the human race. Jelinek seized the novel by its bootstraps and shook it upside down. Was she looking for coins or keys, or just trying to prevent fiction swallowing any more insincerity? Her dynamic writing gives a sense of civilisation surviving against the odds.

Jelinek's work is brave, adventurous, witty, antagonistic and devastatingly right about the sorriness of human existence, and her contempt is expressed with surprising chirpiness: it's a wild ride. She has also developed a form of cubism, whereby she can approach any subject from any angle, sometimes within the same sentence, homing in with sudden tenacity on some detail such as dirndls or murderers' female pen-pals. Recreating the way the brain lurches along, spreads out, reels itself in or goes on strike, her metaphors and puns run amok, beauteousness sacrificed to a kaleidoscopic inventiveness. Wrongly accused here of writing porn, in America she has been criticised, absurdly, for living with her mother, having a website, and not going along with the war in Iraq. They treat her like some kind of moral philosopher. You can't blame a novelist for being provocative and voicing dissent – that's her job! Without novelists, who's to guide us? Scientists? Priests? Politicians?

The innovation in Greed is that Jelinek intrudes more than ever before, rushing in and out of her own book like someone with tummy trouble. She likes to present herself as the bumbling author: "It's a frequent reproach, that I stand around looking stupid and drop my characters, before I even have them, because to be honest I pretty quickly find them dull." She admits to many mistakes: "Oh dear, that doesn't work, and it's also a repetition. Forgive me, I often can't keep up with myself." She hates naming her characters – "It sounds so silly." She identifies a needy piano teacher as a portrait of herself, then proceeds to ridicule and finally destroy her.

What it amounts to is a dismantling of the novel before our eyes. Greed lacks the focus of Jelinek's previous books, and is nearly incoherent at times. It is a cry of despair – despair about herself as a writer as much as about the characters she invents: "What is so wretched about me, that I can only be used for writing?" These are the exasperated outpourings of a great writer suffering from a lack of recognition (the book was written before Jelinek won the Nobel). There's a bewildered, lonely quality to it, as well as a few too many references to current affairs, and some lazy passages that suggest she no longer believes she has any readers at all – and despite that, some wonderful, defiant mischief-making. She can't go on, she will go on.

The plot, involving the semi-accidental murder of a teenage girl and the dumping of her body in an ominous lake, is minimal and haphazard, its main function to flesh out the divisions between men and women. They are on completely different wavelengths, the women in love with a "country policeman", and he latently in love with men, and blatantly with property. There are other greeds, too, that of banks, naturally, and phone companies, "hot for our voices", and the church. Describing a fancy crucifix, Jelinek writes: "the prominent victim is so full of pride at his stiff price that he's almost bursting out of the screws with which he's fastened to his instrument".

But the country policeman's greed surpasses all. He has prostituted himself to every woman in the vicinity and beyond, in the hope that they will hand over their houses to him, or at least leave him something in their wills. He thinks of female genitalia in the same way, all these doors permanently flung open for him. Jelinek circles round him, disgustedly observing that he "completely lacks a whole dimension, that is… that there are other people apart from himself". "We should all hate corporeal life, but only this country policeman… really does hate it. One just doesn't notice at first, because he sometimes jokes and laughs and sings songs to the accordion."

She is equally scathing about women and their repellent eagerness to be loved. Sex is furtive, violent, base – "you give each other a good licking" – and love merely a common foible which, for women at least, always involves a dangerous loss of selfhood. Jelinek gives us a startling glimpse here of what women are, as well as answering Freud's question, "What do women want?" It's neither gentle nor sweet nor safe nor reasonable – just true.

Carole Angier

***

Greed was published in German in 2000, and thus made part of the oeuvre for which Elfriede Jelinek was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2004. Its plot is soon told. Kurt Janisch, an Austrian country policeman, preys on women. He murders a very young one and drives an elderly one to suicide. This is a long novel, but few of its many pages actually advance the plot. Only now and then, as a sort of concession, will a sentence or two tell us what happens next. Greed might be variously described, but not, I think (pace the blurb), as a thriller.

Mostly, Greed consists of digression, commentary and repetition. A reader interested in story will feel consistently thwarted; perhaps also that such an interest is inappropriate. Serious fiction, you might begin to feel, shouldn't pander to readers wanting to know what happens next.

In German (but not in this translation) the novel has a sub-title: Ein Unterhaltungsroman; that is, light reading, or a novel you might read for fun. This term is at least Jelinek's own, a part of her project and the first note of her characteristic tone of voice, which is sardonic. There are many voices in Greed – the women, Janisch, others in their community – but all sound much the same, infected by the sardonic facetiousness of the author herself; so that, despite its variety of perspective, the tone of the whole is remarkably homogeneous. That tone is a slant expression of outrage, sign of Jelinek's moral seriousness. Her plot and its characters are a canker within the canker of Austria, which may itself be an exemplar of things in general.

Janisch is indeed a nasty piece of work. He has brutal sex with women, hates, fears and despises them; but his greed is really for property. Most readers would, I guess, have been able to develop out of Janisch's character and deeds a critique of the most rapacious and murderous tendencies in modern capitalism; Jelinek does it for them. She is a ranter, and there is much to rant about: polluted lakes, mined-out mountains, tourism, sport, old people's homes, the Nazi past, the fascistic present, the traffic… In the ranting, she resembles her compatriot Thomas Bernhard; but he is, blackly speaking, funnier.

Bernhard's sentences give pleasure. Jelinek seems to want to match the ugliness of her subject with a language that, if not always downright ugly, is never attractive. The sentences are made unshapely by the expanding bulk of ridiculed material. Her book steadfastly prohibits what literary language engenders naturally: pleasure. Her translator aids and abets her in this.

All the author's inventiveness goes into the book's lateral expansion. Her procedures are baroque: a heaping up of instances; frequent allegorising; bizarre conceits. You might even call her whimsical. She devises far-fetched ways of saying a thing, to shock us into awareness with a grisly whimsy.

Greed has considerable energy and force. Its moral urgency is beyond doubt. But, reading it, you enter a swirling fog of rage, outrage and sardonic contempt that envelops everything, victims and villain alike, the women in their way being as bad as he is: so foolish, so greedy for affection, gobbling him up, no wonder he is fearful. Throughout it all, insistently, comes the author's own voice, sardonic towards herself, doubting her right and ability do what she is doing. This is the stuff of secondary literature: fiction's failure in the face of life. But a persuasive fiction, one in which the author and readers believe, is more powerful, and can do more good, than Jelinek allows herself to suppose.

David Constantine