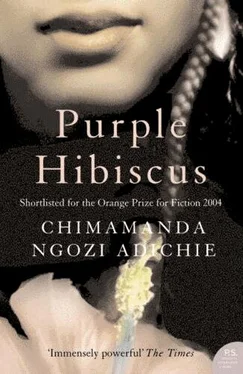

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I took my exams on my hospital bed while Mother Lucy, who brought the papers herself, waited on a chair next to Mama. She gave me extra time for each exam, but I was finished long before the time was up. She brought my report card a few days later. I came first. Mama did not sing her Igbo praise songs; she only said, "Thanks be to God."

My class girls visited me that afternoon, their eyes wide with awed admiration. They had heard I had survived an accident. They hoped I would come back with a cast that they could all scribble their signatures on. Chinwe Jideze brought me a big card that read "Get well soon to someone special," and she sat by my bed and talked to me, in confidential whispers, as if we had always been friends. She even showed me her report card-she had come second. Before they left, Ezinne asked, "You will stop running away after school, now, won't you?"

Mama told me that evening that I would be discharged in two days. But I would not be going home, I would be going to Nsukka for a week, and Jaja would go with me. She did not know how Aunty Ifeoma had convinced Papa, but he had agreed that Nsukka air would be good for me, for my recuperation.

Rain splashed across the floor of the verandah, even though the sun blazed and I had to narrow my eyes to look out the door of Aunty Ifeoma's living room. Mama used to tell Jaja and me that God was undecided about what to send, rain or sun. We would sit in our rooms and look out at the raindrops glinting with sunlight, waiting for God to decide.

"Kambili, do you want a mango?" Obiora asked from behind me.

He had wanted to help me into the flat when we arrived earlier in the afternoon, and Chima had insisted on carrying my bag. It was as if they feared my illness lingered somewhere within and would pounce out if I exerted myself. Aunty Ifeoma had told them mine was a serious illness, that I had nearly died.

"I will eat one later," I said, turning.

Obiora was pounding a yellow mango against the living room wall. He would do that until the inside became a soft pulp. Then he would bite a tiny hole in one end of the fruit and suck it until the seed wobbled alone inside the skin, like a person in oversize clothing. Amaka and Aunty Ifeoma were eating mangoes too, but with knives, slicing the firm orange flesh off the seed. I went out to the verandah and stood by the wet metal railings, watching the rain thin to a drizzle and then stop. God had decided on sunlight. There was the smell of freshness in the air, that edible scent the baked soil gave out at the first touch of rain. I imagined going into the garden, where Jaja was on his knees, digging out a clump of mud with my fingers and eating it. "Aku na-efe! Aku is flying!" a child in the flat upstairs shouted. The air was filling with flapping, water-colored wings. Children ran out of the flats with folded newspapers and empty Bournvita tins. They hit the flying aku down with the newspapers and then bent to pick them up and put them in the tins. Some children simply ran around, swiping at the aku just for the sake of it. Others squatted down to watch the ones that had lost wings crawl on the ground, to follow them as they held on to one another and moved like a black string, a mobi necklace. "Interesting how people will eat aku. But ask them to eat the wingless termites and that's another thing. Yet the wingless ones are just a phase or two away from aku," Obiora said.

Aunty Ifeoma laughed. "Look at you, Obiora. A few years ago, you were always first to run after them."

"Besides, you should not speak of children with such contempt," Amaka teased. "After all, they are your own kind."

"I was never a child," Obiora said, heading for the door.

"Where are you going?" Amaka asked. "To chase aku?"

"I'm not going to run after those flying termites, I am just going to look," Obiora said. "To observe."

Amaka laughed, and Aunty Ifeoma echoed her. "Can I go, Mom?" Chima asked. He was already heading for the door.

"Yes. But you know we will not fry them."

"I will give the ones I catch to Ugochukwu. They fry aku in their house," Chima said.

"Watch that they do not fly into your ears, inugo! Or they will make you go deaf!" Aunty Ifeoma called as Chima dashed outside.

Aunty Ifeoma put on her slippers and went upstairs to talk to a neighbor. I was left alone with Amaka, standing side by side next to the railings. She moved forward to lean on the railings, her shoulder brushing mine. The old discomfort was gone. "You have become Father Amadi's sweetheart," she said. Her tone was the same light tone she had used with Obiora. She could not possibly know how painfully my heart lurched. "He was really worried when you were sick. He talked about you so much. And, amam, it wasn't just priestly concern."

"What did he say?"

Amaka turned to study my eager face. "You have a crush on him, don't you?"

"Crush" was mild. It did not come close to what I felt, how I felt, but I said, "Yes."

"Like every other girl on campus."

I tightened my grip on the railings. I knew Amaka would not tell me more unless I asked. She wanted me to speak out more, after all. "What do you mean?" I asked.

"Oh, all the girls in church have crushes on him. Even some of the married women. People have crushes on priests all the time, you know. It's exciting to have to deal with God as a rival." Amaka ran her hand over the railings, smearing the water droplets. "You're different. I've never heard him talk about anyone like that. He said you never laugh. How shy you are although he knows there's a lot going on in your head. He insisted on driving Mom to Enugu to see you. I told him he sounded like a person whose wife was sick."

"I was happy that he came to the hospital," I said. It felt easy saying that, letting the words roll off my tongue.

Amaka's eyes still bored into me. "It was Uncle Eugene who did that to you, okwia?" she asked.

I let go of the railings, suddenly needing to ease myself. Nobody had asked, not even the doctor at the hospital or Father Benedict. I did not know what Papa had told them. Or if he had even told them anything.

"Did Aunty Ifeoma tell you?" I asked.

"No, but I guessed so."

"Yes. It was him," I said, and then headed for the toilet. I did not turn to see Amaka's reaction.

The power went off that evening, just before the sun fell. The refrigerator shook and shivered and then fell silent. I did not notice how loud its nonstop hum was until it stopped. Obiora brought the kerosene lamps out to the verandah and we sat around them, swatting at the tiny insects that blindly followed the yellow light and bumped against the glass bulbs. Father Amadi came later in the evening, with roast corn and ube wrapped in old newspapers.

"Father, you are the best! Just what I was thinking about, corn and ube," Amaka said.

"I brought this on the condition that you will not raise any arguments today," Father Amadi said. "I just want to see how Kambili is doing."

Amaka laughed and took the package inside to get a plate.

"It's good to see you are yourself again," Father Amadi said, looking me over, as if to see if I was all there. I smiled. He motioned for me to stand up for a hug. His body touching mine was tense and delicious. I backed away. I wished that Chima and Jaja and Obiora and Aunty Ifeoma and Amaka would all disappear for a while. I wished I were alone with him. I wished I could tell him how warm I felt that he was here, how my favorite color was now the same fired-clay shade of his skin.

A neighbor knocked on the door and came in with a plastic container of aku, anara leaves, and red peppers. Aunty Ifeoma said she did not think I should eat any because it might disturb my stomach. I watched Obiora flatten an anara leaf on his palm. He sprinkled the aku, fried to twisted crisps, and the peppers on the leaf and then rolled it up. Some of them slipped out as he stuffed the rolled leaf in his mouth.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)