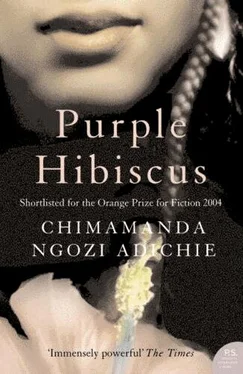

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"No!" I shrieked. I dashed to the pieces on the floor as if to save them, as if saving them would mean saving Papa-Nnukwu. I sank to the floor, lay on the pieces of paper.

"What has gotten into you?" Papa asked. "What is wrong with you?"

I lay on the floor, curled tight like the picture of a child in the uterus in my Integrated Science for Junior Secondary Schools.

"Get up! Get away from that painting!"

I lay there, did nothing.

"Get up!" Papa said again. I still did not move. He started to kick me. The metal buckles on his slippers stung like bites from giant mosquitoes. He talked nonstop, out of control, in a mix of Igbo and English, like soft meat and thorny bones.

Godlessness. Heathen worship. Hellfire. The kicking increased in tempo, and I thought of Amaka's music, her culturally conscious music that sometimes started off with a calm saxophone and then whirled into lusty singing. I curled around myself tighter, around the pieces of the painting; they were soft, feathery. They still had the metallic smell of Amaka's paint palette. The stinging was raw now, even more like bites, because the metal landed on open skin on my side, my back, my legs. Kicking. Kicking. Kicking.

Perhaps it was a belt now because the metal buckle seemed too heavy. Because I could hear a swoosh in the air. A low voice was saying, 'Please, biko, please." More stings. More slaps. A salty wetness warmed my mouth. I closed my eyes and slipped away into quiet.

When I opened my eyes, I knew at once that I was not in my bed. The mattress was firmer than mine. I made to get up, but pain shot through my whole body in exquisite little packets. I collapsed back. "Nne, Kambili. Thank God!" Mama stood up and pressed her hand to my forehead, then her face to mine. "Thank God. Thank God you are awake." Her face felt clammy with tears. Her touch was light, yet it sent needles of pain all over me, starting from my head. It was like the hot water Papa had poured on my feet, except now it was my entire body that burned. Each movement was too painful to even think about.

"My whole body is on fire," I said.

"Shhh," she said. "Just rest. Thank God you are awake."

I did not want to be awake. I did not want to feel the breathing pain at my side. I did not want to feel the heavy hammer knocking in my head. Even taking a breath was agony.

A doctor in white was in the room, at the foot of my bed. I knew that voice; he was a lector in church. He was speaking slowly and precisely, the way he did when he read the first and second readings, yet I could not hear it all. Broken rib. Heal nicely. Internal bleeding. He came close and slowly lifted my shirtsleeve. Injections had always scared me-whenever I had malaria, I prayed I would need to take Novalgin tablets instead of chloroquine injections. But now the prick of a needle was nothing. I would take injections every day over the pain in my body.

Papa's face was close to mine. It seemed so close that his nose almost brushed mine, and yet I could tell that his eyes were soft, that he was speaking and crying at the same time. "My precious daughter. Nothing will happen to you. My precious daughter."

I was not sure if it was a dream. I closed my eyes. When I opened them again, Father Benedict stood above me. He was making the sign of the cross on my feet with oil; the oil smelled like onions, and even his light touch hurt.

Papa was nearby. He, too, was muttering prayers, his hands resting gently on my side. I closed my eyes. "It does not mean anything. They give extreme unction to anyone who is seriously ill," Mama whispered, when Papa and Father Benedict left. I stared at the movement of her lips. I was not seriously ill. She knew that. Why was she saying I was seriously ill? Why was I here in St. Agnes hospital?

"Mama, call Aunty Ifeoma," I said.

Mama looked away. "Nne, you have to rest."

"Call Aunty Ifeoma. Please."

Mama reached out to hold my hand. Her face was puffy from crying, and her lips were cracked, with bits of discolored skin peeling off. I wished I could get up and hug her, and yet I wanted to push her away, to shove her so hard that she would topple over the chair.

Father Amadi's face was looking down at me when I opened my eyes. I was dreaming it, imagining it, and yet I wished that it did not hurt so much to smile, so that I could.

"At first they could not find a vein, and I was so scared." It was Mama's voice, real and next to me. I was not dreaming.

"Kambili. Kambili. Are you awake?" Father Amadi's voice was deeper, less melodious than in my dreams.

"Nne, Kambili, nne." It was Aunty Ifeoma's voice; her face appeared next to Father Amadi's. She had held her braided hair up, in a huge bun that looked like a raffia basket balanced on her head.

I tried to smile. I felt woozy. Something was slipping out of me, slipping away, taking my strength and my sanity, and I could not stop it.

"The medication knocks her out," Mama said. "Nne, your cousins send greetings. They would have come, but they are in school. Father Amadi is here with me. Nne…" Aunty Ifeoma clutched my hand, and I winced, pulling it away. Even the effort to pull it away hurt. I wanted to keep my eyes open, wanted to see Father Amadi, to smell his cologne, to hear his voice, but my eyelids were slipping shut.

"This cannot go on, nwunye m," Aunty Ifeoma said. 'When a house is on fire, you run out before the roof collapses on your head."

"It has never happened like this before. He has never punished her like this before," Mama said.

"Kambili will come to Nsukka when she leaves the hospital."

"Eugene will not agree."

"I will tell him. Our father is dead, so there is no threatening heathen in my house. I want Kambili and Jaja to stay with us, at least until Easter. Pack your own things and come to Nsukka. It will be easier for you to leave when they are not there."

"It has never happened like this before."

"Do you not hear what I have said, gbo?" Aunty Ifeoma said, raising her voice.

"I hear you."

The voices grew too distant, as if Mama and Aunty Ifeoma were on a boat moving quickly to sea and the waves had swallowed their voices. Before I lost their voices, I wondered where Father Amadi had gone.

I opened my eyes hours later. It was dark, and the light bulbs were off. In the glimmer of light from the hallway that streamed underneath the closed door, I could see the crucifix on the wall and Mama's figure on a chair at the foot of my bed.

"Kedu? I will be here all night. Sleep. Rest," Mama said. She got up and sat on my bed. She caressed my pillow; I knew she was afraid to touch me and cause me pain. "Your father has been by your bedside every night these past three days. He has not slept a wink."

It was hard to turn my head, but I did it and looked away.

My private tutor came the following week. Mama said Papa had interviewed ten people before he picked her.

She was a young Reverend Sister and had not yet made her final profession. The beads of the rosary, which were twisted around the waist of her sky-colored habit, rustled as she moved. Her wispy blond hair peeked from beneath her scarf. When she held my hand and said, "Kee ka ime?"

I was stunned. I had never heard a white person speak Igbo, and so well. She spoke softly in English when we had lessons and in Igbo, although not often, when we didn't. She created her own silence, sitting in it and fingering her rosary while I read comprehension passages. But she knew a lot of things; I saw it in the pools of her hazel eves. She knew, for example, that I could move more body parts than I told the doctor, although she said nothing. Even the hot pain in my side had become lukewarm, the throbbing in my head had lessened. But I told the doctor it was as bad as before and I screamed when he tried to feel my side. I did not want to leave the hospital. I did not want to go home.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)