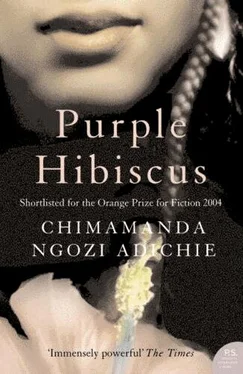

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Have you picked a confirmation name?" I asked.

"No," Amaka said. "Ngwanu, Mom wants to remind Aunty Beatrice of something."

"Greet Chima and Obiora," I said, before I handed the phone to Mama.

Back in my room, I stared at my textbook and wondered if Father Amadi had really asked about us or it Aunty Ifeoma had said so out of courtesy, so it would be that he remembered us, just as we remembered him. But Aunty Ifeoma was not like that. She would not say it if he had not asked. I wondered if he had asked about us, Jaja and me at the same time, like asking about two things that went together. Corn and ube. Rice and stew. Yam and oil. Or if he had separated us, asked about me and then about Jaja. When I heard Papa come home from work, I roused myself and looked at my book. I had been doodling on a sheet of paper, stick figures, and "Father Amadi" written over and over again. I tore up the piece of paper.

I tore up many more in the following weeks. They all had "Father Amadi" written over and over again. On some I tried to capture his voice, using the symbols of music. On others I formed the letters of his name using Roman numerals. I did not need to write his name down to see him, though. I recognized a flash of his gait, that loping, confident stride, in the gardeners. I saw his lean, muscular build in Kevin and, when school resumed, even a flash of his smile in Mother Lucy.

I joined the group of girls on the volleyball field on the second day of school. I did not hear the whispers of "backyard snob" or the ridiculing laughter. I did not notice the amused pinches they gave one another. I stood waiting with my hands clasped until I was picked. I saw only Father Amadi's clay-coiored face and heard only "You have good legs for running."

It rained heavily the day Ade Coker died, strange, furious rain in the middle of the parched harmattan. Ade Coker was at breakfast with his family when a courier delivered a package to him. His daughter, in her primary school uniform, was sitting across the table from him. The baby was nearby, in a high chair. His wife was spooning Cerelac into the baby's mouth. Ade Coker was blown up when he opened the package-a package everybody would have known was from the Head of State even if his wife Yewande had not said that Ade Coker looked at the envelope and said "It has the State House seal" before he opened it.

When Jaja and I came home from school, we were almost drenched by the walk from the car to the front door; the rain was so heavy it had formed a small pool beside the hibiscuses. My feet itched inside my wet leather sandals. Papa was crumpled on a sofa in the living room, sobbing. He seemed so small.

Papa who was so tall that he sometimes lowered his head to get through doorways, that his tailor always used extra fabric to sew his trousers. Now he seemed small; he looked like a rumpled roll of fabric.

"I should have made Ade hold that story," Papa was saving. "I should have protected him. I should have made him stop that story."

Mama held him close to her, cradling his face on her chest. "No," she said. "O zugo. Don't."

Jaja and I stood watching. I thought about Ade Coker's glasses, I imagined the thick, bluish lenses shattering, the white frames melting into sticky goo. Later, after Mama told us what had happened, how it had happened, Jaja said, "It was God's will, Papa," and Papa smiled at Jaja and gently patted his back.

Papa organized Ade Coker's funeral; he set up a trust for Yewande Coker and the children, bought them a new house. He paid the Standard staff huge bonuses and asked them all to take a long leave. Hollows appeared under his eyes during those weeks, as if someone had suctioned the delicate flesh, leaving his eyes sunken in.

My nightmares started then, nightmares in which I saw Ade Coker's charred remains spattered on his dining table, on his daughters school uniform, on his baby's cereal bowl, on his plate of eggs. In some of the nightmares, I was the daughter and the charred remains became Papa's.

Weeks after Ade Coker died, the hollows were still carved under Papas eyes, and there was a slowness in his movements, as though his legs were too heavy to lift, his hands too heavy to swing. He took longer to reply when spoken to, to chew his food, even to find the right Bible passages to read. But he prayed a lot more, and some nights when I woke up to pee, I heard him shouting from the balcony overlooking the front yard. Even though I sat on the toilet seat and listened, I never could make sense of what he was saying. When I told Jaja about this, he shrugged and said that Papa must have been speaking in tongues, although we both knew that Papa did not approve of people speaking in tongues because it was what the fake pastors at those mushroom Pentecostal churches did. Mama told Jaja and me often to remember to hug Papa tighter, to let him know we were there, because he was under so much pressure.

Soldiers had gone to one of the factories, carrying dead rats in a carton, and then closed the factory down, saying the rats had been found there and could spread. disease through the wafers and biscuits. Papa no longer went to the other factories as often as he used to. Some days, Father Benedict came before Jaja and I left for school, and was still in Papa's study when we came home. Mama said they were saying special novenas.

Papa never came out to make sure Jaja and I were following our schedules on such days, and so Jaja came into my room to talk, or just to sit on my bed while I studied, before going to his room. It was on one of those days that Jaja came into my room, shut the door, and asked, "Can I see the painting of Papa-Nnukwu?"

My eyes lingered on the door. I never looked at the painting when Papa was at home. "He is with Father Benedict," Jaja said. "He will not come in."

I took the painting out of the bag and unwrapped it.

Jaja stared at it, running his deformed finger over the paint, the finger that had very little feeling. "I have Papa-Nnukwus arms," Jaja said. "Can you see? I have his arms."

He sounded like someone in a trance, as if he had forgotten where he was and who he was. As if he had forgotten that his finger had little feeling in it.

I did not tell Jaja to stop, or point out that it was his deformed finger that he was running over the painting. I did not put the painting right back. Instead I moved closer to Jaja and we stared at the painting, silently, for a very long time. A long enough time for Father Benedict to leave. I knew Papa would come in to say good night, to kiss my forehead. I knew he would be wearing his wine-red pajamas that lent a slightly red shimmer to his eyes. I knew Jaja would not have enough time to slip the painting back in the bag, and that Papa would take one look at it and his eyes would narrow, his cheeks would bulge out like unripe udala fruit, his mouth would spurt Igbo words.

And that was what happened. Perhaps it was what we wanted to happen, Jaja and I, without being aware of it. Perhaps we all changed after Nsukka-even Papa-and things were destined to not be the same, to not be in their original order.

"What is that? Have you all converted to heathen ways? What are you doing with that painting? Where did you get it?" Papa asked.

"O nkem. It's mine," Jaja said. He wrapped the painting around his chest with his arms.

"It's mine," I said.

Papa swayed slightly, from side to side, like a person about to fall at the feet of a charismatic pastor after the laying on of hands. Papa did not sway often. His swaying was like shaking a bottle of Coke that burst into violent foam when you opened it. "Who brought that painting into this house?"

"Me," I said.

"Me," Jaja said. If only Jaja would look at me, I would ask him not to blame himself.

Papa snatched the painting from Jaja. His hands moved swiftly, working together. The painting was gone. It already represented something lost, something I had never had, would never have. Now even that reminder was gone, and at Papa's feet lay pieces of paper streaked with earth-tone colors. The pieces were very small, very precise. I suddenly and maniacally imagined Papa-Nnukwu's body being cut in pieces that small and stored in a fridge.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)