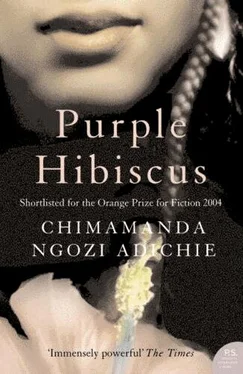

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Papa stared at her for a while, surprise widening the narrow eyes that so easily became red-spotted. "When?"

"This morning. In his sleep. They took him to the mortuary just hours ago."

Papa sat down and slowly lowered his head into his hands, and I wondered if he was crying, if it would be acceptable for me to cry, too. But when he looked up, I did not see the traces of tears in his eyes. "Did you call a priest to give him extreme unction?" he asked.

Aunty Ifeoma ignored him and continued to look at her hands, folded in her lap. "Ifeoma, did you call a priest?" Papa asked.

"Is that all you can say, eh, Eugene? Have you nothing else to say, gbo? Our father has died! Has your head turned upside down? Will you not help me bury our father?"

"I cannot participate in a pagan funeral, but we can discuss with the parish priest and arrange a Catholic funeral."

Aunty Ifeoma got up and started to shout. Her voice was unsteady. "I will put my dead husband's grave up for sale, Eugene, before I give our father a Catholic funeral. Do you hear me? I said I will sell Ifediora's grave first! Was our father a Catholic? I ask you, Eugene, was he a Catholic? Uchu gha gi!" Aunty Ifeoma snapped her fingers at Papa; she was throwing a curse at him. Tears rolled down her cheeks. She made choking sounds as she turned and walked into her bedroom.

"Kambili and Jaja, come," Papa said, standing up. He hugged us at the same time, tightly. He kissed the tops of our heads, before saying, "Go and pack your bags."

In the bedroom, most of my clothes were in the bag already. I stood staring at the window with the missing louvers and the torn mosquito netting, wondering what it would be like if I tore through the small hole and leaped out.

"Nne." Aunty Ifeoma came in silently and ran a hand over my cornrows. She handed me my schedule, still folded in crisp quarters. "Tell Father Amadi that I have left, that we have left, say good-bye for us," I said, turning. She had wiped the tears from her face, and she looked the same again, fearless.

"I will," she said. She held my hand in hers as we walked to the front door.

Outside, the harmatten wind tore across the front yard, ruffling the plants in the circular garden, bending the will and branches of trees, coating the parked cars with more dust. Obiora carried our bags to the Mercedes, where Kevin waited with the boot open. Chima started to cry; I knew he did not want Jaja to leave.

"Chima, o zugo. You will see Jaja again soon. They will come again," Aunty Ifeoma said, holding him close.

Papa did not say yes to back up what Aunty Ifeoma had said. Instead, to make Chima feel better he said, "O zugo, it's enough," hugged Chima, and stuffed a small wad of naira notes into Aunty Ifeoma's hand to buy Chima a present, which made Chima smile. Amaka blinked rapidly as she said good-bye, and I was not sure if it was from the gritty wind or to keep more tears back. The dust coating her eyelashes looked stylish, like cocoa-colored mascara. She pressed something wrapped in black cellophane into my hands, then turned and hurried back into the flat.

I could see through the wrapping: it was the unfinished painting of Papa-Nnukwu. I hid it in my bag, quickly, and climbed into; the car.

Mama was at the door when we drove into our compound. Her face was swollen and the area around her right eye was the black-purple shade of an overripe avocado. She was smiling. "Umu m, welcome. Welcome." She hugged us at the same time, burying her head in Jaja's neck and then in mine. "It seems so long, so much longer than ten days."

"Ifeoma was busy tending to a heathen," Papa said, pouring a glass of water from a bottle Sisi placed on the table. "She did not even take them to Aokpe on pilgrimage."

"Papa-Nnukwu is dead," Jaja said.

Mama's hand flew to her chest. "Chi m! When?"

"This morning," Jaja said. "He died in his sleep."

Mama wrapped her hands around herself. "Etwuu, so he has gone to rest, etvuu".

"He has gone to face judgment," Papa said, putting his glass of water down. "Ifeoma did not have the sense to call a priest before he died. He might have converted before he died."

"Maybe he didn't want to convert," Jaja said.

"May he rest in peace," Mama said quickly.

Papa looked at Jaja. "What did you say? Is that what you have learned from living in the same house as a heathen?"

"No," Jaja said.

Papa stared at Jaja, then at me, shaking his head slowly as if we had somehow changed color. "Go and bathe and come down for dinner," he said. As we went upstairs, Jaja walked in front of me and I tried to place my feet on the exact spots where he placed his.

Papa's prayer before dinner was longer than usual: he asked God to cleanse his children, to remove whatever spirit it was that made them lie to him about being in the same house as a heathen. "It is the sin of omission, Lord," he said, as though God did not know. I said my "amen" loudly.

Dinner was beans and rice with chunks of chicken. As I ate, I thought how each chunk of chicken on my plate would be cut into three pieces in Aunty Ifeoma's house.

"Papa, may I have the key to my room, please?" Jaja asked, setting his fork down. We were halfway through dinner. I took a deep breath and held it. Papa had always kept the keys to our rooms.

"What?" Papa asked.

"The key to my room. I would like to have it. Makana, because I would like some privacy."

Papa's pupils seemed to dart around in the whites of his eyes. "What? What do you want privacy for? To commit a sin against your own body? Is that what you want to do, masturbate?"

"No," Jaja said. He moved his hand and knocked his glass of water over.

"See what has happened to my children?" Papa asked the ceiling. "See how being with a heathen has changed them, has taught them evil?"

We finished dinner in silence. Afterward, Jaja followed Papa upstairs. I sat with Mama in the living room, wondering why Jaja had asked for the key. Of course Papa would never give it to him, he knew that, knew that Papa would never let us lock our doors. For a moment, I wondered if Papa was right, if being with Papa-Nnukwu had made Jaja evil, had made us evil.

"It feels different to be back, okwia?" Mama asked. She was looking through samples of fabric, to pick out a shade for the new curtains. We replaced the curtains every year, toward the end of harmattan. Kevin brought samples for Mama to look at, and she picked some and showed Papa, so he could make the final decision. Papa usually chose her favorite. Dark beige last year. Sand beige the year before. I wanted to tell Mama that it did feel different to be back, that our living room had too much empty space, too much wasted marble floor that gleamed from Sisi's polishing and housed nothing. Our ceilings were too high. Our furniture was lifeless: the glass tables did not shed twisted skin in the harmattan, the leather sofas' greeting was a clammy coldness, the Persian rugs were too lush to have any feeling. But I said, "You polished the etagere."

"Yes."

"When?"

"Yesterday."

I stared at her eye. It appeared to be opening now; it must have been swollen completely shut yesterday.

"Kambili!" Papa's voice carried clearly from upstairs. I held my breath and sat still. "Kambili!"

"Nne, go," Mama said.

I went upstairs slowly. Papa was in the bathroom, with the door ajar. I knocked on the open door and stood by, wondering why he had called me when he was in the bathroom. "Come in," he said. He was standing by the tub. "Climb into the tub."

I stared at Papa. Why was he asking me to climb into the tub? I looked around the bathroom floor; there was no stick anywhere. Maybe he would keep me in the bathroom and then go downstairs, out through the kitchen, to break a stick off one of the trees in the backyard. When Jaja and I were younger, from elementary two until about elementary five, he asked us to get the stick ourselves. We always chose whistling pine because the branches were malleable, not as painful as the stiffer branches from the gmelina or the avocado. And Jaja soaked the sticks in cold water because he said that made them less painful when they landed on your body. The older we got, though, the smaller the branches we brought, until Papa started to go out himself to get the stick.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)