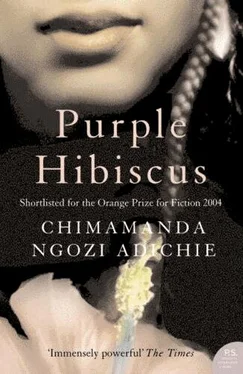

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I nodded stiffly, although Aunty Ifeoma could not see me. I had never thought about the university, where I would go or what I would study. When the time came, Papa would decide.

Aunty Ifeoma horned and waved at two balding men in tie dye shirts standing at a corner as she turned. She switched the ignition off again, and the car hurtled down the street. Gmelina and dogonyaro trees stood firmly on either side. The sharp, astringent scent of the dogonyaro leaves filled the car, and Amaka breathed deeply and said they cured malaria. We were in a residential area, driving past bungalows in wide compounds with rose bushes and faded lawns and fruit trees. The street gradually lost its tarred smoothness and its cultivated hedges, and the houses became low and narrow, their front doors so close together that you could stand at one, stretch out, and touch the next door. There was no pretense at hedges here, no pretense at separation or privacy, just low buildings side by side amid a scattering of stunted shrubs and cashew trees. These were the junior-staff quarters, where the secretaries and drivers lived, Aunty Ifeoma explained, and Amaka added, "If they are lucky enough to get it."

We had just driven past the buildings when Aunty Ifeoma pointed to the right and said, "There is Odim hill. The view from the top is breathtaking, when you stand there, you see just how God laid out the hills and valleys, ezi oktvu." When she made a U-turn and went back the way we had come, I let my mind drift, imagining God laying out the hills of Nsukka with his wide white hands, crescent-moon shadows underneath his nails just like Father Benedict's. We drove past the sturdy trees around the faculty of engineering, past the vast mango-filled fields around the female hostels. Aunty Ifeoma turned the opposite way when she got close to her street. She wanted to show us the other side of Marguerite Cartwright Avenue, where the seasoned professors lived, with the duplexes hemmed in by gravely driveways.

"I hear that when they first built these houses, some of the white professors-all the professors were white back then-wanted chimneys and fireplaces," Aunty Ifeoma said, with the same kind of indulgent laugh that Mama let out when she talked about people who went to witch doctors. She then pointed to the vice chancellor's lodge, to the high walls surrounding it, and said it used to have well-tended hedges of cherry and ixora until rioting students jumped over the hedges and burned a car in the compound.

"What was the riot about?" Jaja asked.

"Light and water," Obiora said, and I looked at him.

"There was no light and no water for a month," Aunty Ifeoma added. "The students said they could not study and asked if the exams could be rescheduled, but they were refused."

"The walls are hideous," Amaka said, in English, and I wondered what she would think of our compound walls back home, if she ever visited us. The V.C.'s walls were not very high; I could see the big duplex that nestled behind a canopy of trees with greenish-yellow leaves. "Putting up walls is all superficial fix, anyway," she continued. "If I were the VC, the students would not riot. They would have water and light."

"If some Big Man in Abuja has stolen the money, is the V.C. supposed to vomit money for Nsukka?" Obiora asked.

I turned to watch him, imagining myself at fourteen, imagining myself now.

"I wouldn't mind somebody vomiting some money for me, right now" Aunty Ifeoma said, laughing in that proud-coach-watching-the-team way. "We'll go into town to see if there is any decently priced ube in the market. I know Father Ama likes ube, and we have some corn at home to go with it."

"Will the fuel make it, Mom?" Obiora asked.

"Amarom, we can try." Aunty Ifeoma rolled the car down the road that led to the university entrance gates. Jaja turned to the statue of the preening lion as we drove past it, his lips moving soundlessly. To restore the dignity of man. Obiora was reading the plaque, too. He let out a short cackle and asked, "But when did man lose his dignity?"

Outside the gate, Aunty Ifeoma started the ignition again. When the car shuddered without starting, she muttered, "Blessed Mother, please not now," and tried again. The car only whined. Somebody horned behind us, and I turned to look at the woman in the yellow Peugeot 504. She came out and walked toward us; she wore a pair of culottes that flapped around her calves, which were lumpy like sweet potatoes. "My own car stopped near Eastern Shop yesterday." The woman stood at Aunty Ifeoma's window, her hair in a riotous curly perm swaying in the wind. "My son sucked one liter from my husband's car this morning, just so I can get to the market. O di egwu. I hope fuel comes soon."

"Let us wait and see, my sister. How is the family?" Aunty Ifeoma asked.

"We are well. Go well."

"Let's push it," Obiora suggested, already opening the car door.

"Wait." Aunty Ifeoma turned the key again, and the car shook and then started. She drove off, with a screech, as if she did not want to slow down and give the car another chance to stop.

We stopped beside an ube hawker by the roadside, her bluish fruits displayed in pyramids on an enamel tray. Aunty Ifeoma gave Amaka some crumpled notes from her purse. Amaka bargained with the trader for a while, and then she smiled and pointed at the pyramids she wanted. I wondered what it felt like to do that.

Back in the flat, I joined Aunty Ifeoma and Amaka in the kitchen while Jaja went off with Obiora to play football with the children from the flats upstairs. Aunty Ifeoma got one of the huge yams we had brought from home. Amaka spread newspaper sheets on the floor to slice the tuber; it was easier than picking it up and placing it on the counter. When Amaka put the yam slices in a plastic bowl, I offered to help peel them and she silently handed me a knife.

"You will like Father Amadi, Kambili," Aunty Ifeoma said. "He's new at our chaplaincy, but he is so popular with everybody on campus already. He has invitations to eat in everybody's house."

"I think he connects with our family the most," Amaka said.

Aunty Ifeoma laughed. "Amaka is so protective of him."

"You are wasting yam, Kambili," Amaka snapped. "Ah! Ah! Is that how you peel yam in your house?"

I jumped and dropped the knife. It fell an inch away from my foot. "Sorry," I said, and I was not sure ii it was for dropping the knife or for letting too much creamy white yam go with the brown peel.

Aunty Ifeoma was watching us. "Amaka, ngwa, show Kambili how to peel it."

Amaka looked at her mother with her lips turned down and her eyebrows raised, as if she could not believe that anybody had to be told how to peel yam slices properly. She picked up the knife and started to peel a slice, letting only the brown skin go. I watched the measured movement of her hand and the increasing length of the peel, wishing I could apologize, wishing I knew how to do it right. She did it so well that the peel did not break, a continuous twirling soil-studded ribbon.

"Maybe I should enter it in your schedule, how to peel a yam," Amaka muttered.

"Amaka!" Aunty Ifeoma shouted. "Kambili, get me some water from the tank outside."

I picked up the bucket, grateful for Aunty Ifeoma, for the chance to leave the kitchen and Amaka's scowling face. Amaka did not talk much the rest of the afternoon, until Father Amadi arrived, in a whiff of an earthy cologne. Chima jumped on him and held on. He shook Obiora's hand. Aunty Ifeoma and Amaka gave him brief hugs, and then Aunty Ifeoma introduced Jaja and me. "Good evening," I said and then added, "Father." It felt almost sacrilegious addressing this boyish man-in an open neck T-shirt and jeans faded so much I could not tell if they had been black or dark blue-as Father.

"Kambili and Jaja," he said, as if he had met us before. "How are you enjoying your first visit to Nsukka?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)