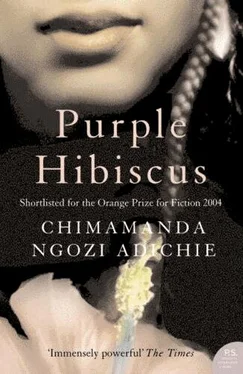

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I wondered where Jaja and I would be sleeping, and as if Aunty Ifeoma had read my thoughts, she said, "You and Amaka will sleep here, nne. Obiora sleeps in the living room so Jaja will stay with him."

I heard Kevin and Jaja come into the flat.

"We have finished bringing the things in, Mah. I'm leaving now," Kevin said. He spoke from the living room, but the flat was so small he did not have to raise his voice.

"Tell Eugene I said thank you. Tell him we are well. Drive carefully."

"Yes, Mah."

I watched Kevin leave, and suddenly my chest felt tight. I wanted to run after him, to tell him to wait while I got my bag and got back in the car.

"Nne, Jaja, come and join me in the kitchen until your cousins come back." Aunty Ifeoma sounded so casual, as if it were completely normal to have us visit, as if we had visited so many times in the past. Jaja led the way into the kitchen and sat down on a low wooden stool. I stood by the door because there was hardly enough room in the kitchen not to get in her way, as she drained rice at the sink, checked on the cooking meat, blended tomatoes in a mortar. The light blue kitchen tiles were worn and chipped at the corners, but they looked scrubbed clean, as did the pots, whose lids did not fit, one side slipping crookedly into the pot. The kerosene stove was on a wooden table by the window. The walls near the window and the threadbare curtains had turned black-gray from the kerosene smoke.

Aunty Ifeoma chattered as she put the rice back on the stove and chopped two purple onions, her stream of sentences punctuated by her cackling laughter. She seemed to be laughing and crying at the same time because she reached up often to brush away the onion tears with the back of her hand. Her children came in a few minutes later. They looked different, maybe because I was seeing them for the first time in their own home rather than in Abba, where they were visitors in Papa-Nnukwu's house. Obiora took off a dark pair of sunglasses and slipped them in the pockets of his shorts as they came in. He laughed when he saw me.

"Jaja and Kambili are here!" Chima piped. We all hugged in greeting, brief clasps of our bodies. Amaka barely let her sides meet mine before she backed away. She was wearing lipstick, a different shade that was more red than brown, and her dress was molded to her lean body.

"How was the drive down here?" she asked, looking at Jaja.

"Fine," Jaja said. "I thought it would be longer than it was."

"Oh, Enugu really isn't that far from here," Amaka said.

"We still haven't bought the soft drinks, Mom," Obiora said.

"Did I not tell you to buy them before you left, gbo?" Aunty Ifeoma slid the onion slices into hot oil and stepped back.

"I'll go now. Jaja, do you want to come with me? We're just going to a kiosk in the next compound."

"Don't forget to take empty bottles," Aunty Ifeoma said. I watched Jaja leave with Obiora. I could not see his face. I could not tell if he felt as bewildered as I did.

"Let me go and change, Mom, and I'll fry the plantains!! Amaka said, turning to leave.

"Nne, go with your cousin," Aunty Ifeoma said to me. I followed Amaka to her room, placing one frightened foot after the next. The cement floors were rough, did not let my feet glide over them the way the smooth marble floors back home did. Amaka took her earrings off, placed them on top off the dresser, and looked at herself in the full-length mirror. I sat on the edge of the bed, watching her, wondering if she knew that I had followed her into the room.

"I'm sure you think Nsukka is uncivilized compared to Enugu," she said, still looking in the mirror. "I told Mom to stop forcing you both to come."

"I… we… wanted to come."

Amaka smiled into the mirror, a thin, patronizing smile that seemed to say I should not have bothered lying to her. "There's no happening place in Nsukka, in case you haven't realized that already. Nsukka has no Genesis or Nike Lake."

"What?"

"Genesis and Nike Lake, the happening places in Enugu. You go there all the time, don't you?"

"No."

Amaka gave me an odd look. "But you go once in a while?"

"I… yes." I had never been to the restaurant Genesis and had only been to the hotel Nike Lake when Papa's business partner had a wedding reception there. We had stayed only long enough for Papa to take pictures with the couple and give them a present.

Amaka picked up a comb and ran it through the ends of her short hair. Then she turned to me and asked, "Why do you lower your voice?"

"What?"

"You lower your voice when you speak. You talk in whispers."

"Oh," I said, my eyes focused on the desk, which was full of things-books, a cracked mirror, felt-tipped pens. Amaka put the comb down and pulled her dress over her head. In her white lacy bra and light blue underwear, she looked like a Hausa goat: brown, long and lean. I quickly averted my gaze. I had never seen anyone undress; it was sinful to look upon another person's nakedness.

"I'm sure this is nothing close to the sound system in your room in Enugu," Amaka said. She pointed at the small cassete player at the foot of the dresser. I wanted to tell her that I die not have any kind of music system in my room back home, but I was not sure she would be pleased to hear that, just as she would not be pleased to hear it if I did have one. She turned the cassette player on, nodding to the polyphonic beat of drums. "I listen mostly to indigenous musicians. They're culturally conscious; they have something real to say. Fela and Osadebe and Onyeka are my favorites. Oh, I'm sure you probably don't know who they are, I'm sure you're into American pop like other teenagers." She said "teenagers" as if she were not one, as if teenagers were a brand of people who, by not listening to culturally conscious music, were a step beneath her. And she said "culturally conscious" in the proud way that people say a word they never knew they would learn til they do.

I sat still on the edge of the bed, hands clasped, wanting to tell Amaka that I did not own a cassette player, that I could hardly tell any kinds of pop music apart. "Did you paint this?" I asked, instead. The watercolor painting of a woman with a child was much like a copy of the Virgin and Child oil painting that hung in Papa's bedroom, except the woman and child in Amaka's painting were dark-skinned.

"Yes, I paint sometimes."

"It's nice." I wished that I had known that my cousin painted realistic watercolors. I wished that she would not keep looking at me as if I were a strange laboratory animal to be explained and catalogued.

"Did something hold you girls in there?" Aunty Ifeoma called from the kitchen. I followed Amaka back to the kitchen and watched her slice and fry the plantains. Jaja soon came back with the boys, the bottles of soft drinks in a black plastic bag. Aunty Ifeoma asked Obiora to set the table. "Today we'll treat Kambili and Jaja as guests, but from tomorrow they will be family and join in the work," she said.

The dining table was made of wood that cracked in dry weather. The outermost layer was shedding, like a molting cricket, brown slices curling up from the surface. The dining chairs were mismatched. Four were made of plain wood, the land of chairs in my classroom, and the other two were black and padded. Jaja and I sat side by side. Aunty Ifeoma said the grace, and after my cousins said "Amen," I still had my eyes closed.

"Nne, we have finished praying. We do not say Mass in the name of grace like your father does," Aunty Ifeoma said with a chuckle.

I opened my eyes, just in time to catch Amaka watching me.

"I hope Kambili and Jaja come every day so we can eat like this. Chicken and soft drinks!" Obiora pushed at his glasses as he spoke.

"Mommy! I want the chicken leg," Chima said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)