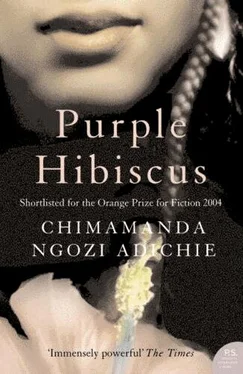

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I think these people have started to put less Coke in the bottles," Amaka said, holding her Coke bottle back to examine it. I looked down at the jollof rice, fried plantains, and half of a drumstick on my plate and tried to concentrate, tried to get the food down. The plates, too, were mismatched. Chima and Obiora used plastic ones while the rest of us had plain glass plates, bereft of dainty flowers or silver lines. Laughter floated over my head. Words spurted from everyone, often not seeking and not getting any response. We always spoke with a purpose back home, especially at the table, but my cousins seemed to simply speak and speak and speak.

"Mom, biko, give me the neck," Amaka said.

"Didn't you talk me out of the neck the last time, gfoop'?" Aunty Ifeoma asked, and then she picked up the chicken neck on her plate and reached across to place it on Amaka's plate.

"When was the last time we ate chicken?" Obiora asked.

"Stop chewing like a goat, Obiora!" Aunty Ifeoma said.

"Goats chew differently when they ruminate and when they eat, Mom. Which do you mean?"

I looked up to watch Obiora chewing. "Kambili, is something wrong with the food?" Aunty Ifeona asked, startling me. I had felt as if I were not there, that I was just observing a table where you could say anything at any time to anyone, where the air was free for you to breathe as you wished.

"I like the rice, Aunty, thank you."

"If you like the rice, eat the rice," Aunty Ifeoma said.

"Maybe it is not as good as the fancy rice she eats at home," Amaka said.

"Amaka, leave your cousin alone," Aunty Ifeoma said.

I did not say anything else until lunch was over, but I listened to every word spoken, followed every cackle of laughter and line of banter. Mostly, my cousins did the talking and Aunty Ifeoma sat back and watched them, eating slowly. She looked like a football coach who had done a good job with her team and was satisfied to stand next to the eighteen-yard box and watch.

After lunch, I asked Amaka where I could ease myself, although I knew that the toilet was the door opposite the bedroom. She seemed irritated by my question and gestured vaguely toward the hall, asking, "Where else do you think?" The room was so narrow I could touch both walls if I stretched out my hands. There were no soft rugs, no furry cover for the toilet seat and lid like we had back home. An empty plastic bucket was near the toilet. After I urinated, I wanted to flush but the cistern was empty; the lever went limply up and down. I stood in the narrow room for a few minutes before leaving to look for Aunty Ifeoma. She was in the kitchen, scrubbing the sides of the kerosene stove with a soapy sponge.

"I will be very miserly with my new gas cylinders," Aunty Ifeoma said, smiling, when she saw me. "I'll use them only for special meals, so they will last long. I'm not packing away this kerosene stove just yet."

I paused because what I wanted to say was so far removed from gas cookers and kerosene stoves. I could hear Obiora's laughter from the verandah. "Aunty, there's no water to flush the toilet."

"You urinated?"

"Yes."

"Our water only runs in the morning, o di egwu. So we don't flush when we urinate, only when there is actually something to flush. Or sometimes, when the water does not run for a few days, we just close the lid until everybody has gone and then we flush with one bucket. It saves water." Aunty Ifeoma was smiling ruefully.

"Oh," I said.

Amaka had come in as Aunty Ifeoma spoke. I watched her walk to the refrigerator. "I'm sure that back home you flush every hour, just to keep the water fresh, but we don't do here," she said.

"Amaka, o gini? I don't like that tone!" Aunty Ifeoma said.

"Sorry," Amaka muttered, pouring cold water from a plastic bottle into a glass. I moved closer to the wall darkened by kerosene smoke, wishing I could blend into it and disappear. I wanted to apologize to Amaka, but I was not sure what for.

"Tomorrow, we will take Kambili and Jaja around to show them the campus," Aunty Ifeoma said, sounding so normal that I wondered if I had just imagined the raised voice.

"There's nothing to see. They will be bored."

The phone rang then, loud and jarring, unlike the mute purr of ours back home. Aunty Ifeoma hurried to her bedroom to pick it up. "Kambili! Jaja!" she called out a moment later. I knew it was Papa. I waited for Jaja to come in from the verandah so we could go in together. When we got to the phone, Jaja stood back and gestured that I speak first. "Hello, Papa. Good evening," I said, and then I wondered if he could tell that I had eaten after saying a too short prayer.

"How are you?"

"Fine, Papa."

"The house is empty without you."

"Oh."

"Do you need anything?"

"No, Papa."

"Call at once if you need anything, and I will send Kevin. I'll call every day. Remember to study and pray."

"Yes, Papa."

When Mama came on the line, her voice sounded louder than her usual whisper, or perhaps it was just the phone. She told me Sisi had forgotten we were away and cooked lunch for four.

When Jaja and I sat down to have dinner that evening, I thought about Papa and Mama, sitting alone at our wide dining table. We had the leftover rice and chicken. We drank water because the soft drinks bought in the afternoon were finished. I thought about the always full crates of Coke and Fanta and Sprite in the kitchen store back home and then quickly gulped my water down as if I could wash away the thoughts. I knew that if Amaka could read thoughts, mine would not please her.

There was less talk and laughter at dinner because the TV was on and my cousins took their plates to the living room. The older two ignored the sofa and chairs to settle on the floor while Chima curled up on the sofa, balancing his plastic plate on his lap. Aunty Ifeoma asked Jaja and me to go and sit in the living room, too, so we could see the TV clearly. I waited to hear Jaja say no, that we did not mind sitting at the dining table, before I nodded in agreement.

Aunty Ifeoma sat with us, glancing often at the TV as she ate. "I don't understand why they fill our television with second rate Mexican shows and ignore all the potential our people have," she muttered.

"Mom, please don't lecture now," Amaka said.

"It's cheaper to import soap operas from Mexico," Obiorftj said, his eyes still glued to the television.

Aunty Ifeoma stood up. "Jaja and Kambili, we usually say the rosary every night before bed. Of course, you can stay up as long as you want afterward to watch TV or whatever else."

Jaja shifted on his chair before pulling his schedule out of his pocket. "Aunty, Papa's schedule says we should study in the evenings; we brought our books."

Aunty Ifeoma stared at the paper in Jaja's hand. Then she started to laugh so hard that she staggered, her tall body bending like a whistling pine tree on a windy day. "Eugene gave you a schedule to follow when you're here? Nekwanu anya, what does that mean?" Aunty Ifeoma laughed some more before she held out her hand and asked for the sheet of paper. When she turned to me, I brought mine, folded in crisp quarters, out of my skirt pocket.

"I will keep them for you until you leave."

"Aunty…" Jaja started.

"If you do not tell Eugene, eh, then how will he know that you did not follow the schedule, gbo? You are on holiday here, and it is my house, so you will follow my own rules."

I watched Aunty Ifeoma walk into her room with our schedules. My mouth felt dry, my tongue clinging to the roof.

"Do you have a schedule at home that you follow every day?" Amaka asked. She lay face up on the floor, her head resting on one of the cushions from a chair.

"Yes," Jaja said.

"Interesting. So now rich people can't decide what to do day by day, they need a schedule to tell them."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)