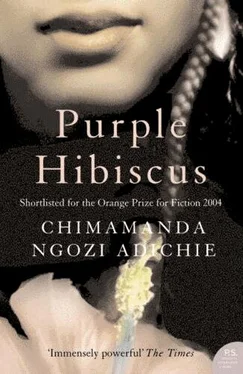

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"They hate it," Amaka said, and I immediately wished she hadn't.

"Nsukka has its charms," Father Amadi said, smiling. He had a singer's voice, a voice that had the same effect on my ears that Mama working Pears baby oil into my hair had on my scalp. I did not fully comprehend his English-laced Igbo sentences at dinner because my ears followed the sound and not the sense of his speech. He nodded as he chewed his yam and greens, and he did not speak until he had swallowed a mouthful and sipped some water. He was at home in Aunty Ifeoma's house; he knew which chair had a protruding nail and could pull a thread off your clothes. "I thought I knocked that nail in," he said, then talked about football with Obiora, the journalist the government had just arrested with Amaka, the Catholic women's organization with Aunty Ifeoma, and the neighborhood video game with Chima. My cousins chattered as much as before, but they waited until Father Amadi said something first and then pounced on it in response. I thought of the fattened chickens Papa sometimes bought for our offertory procession, the ones we took to the altar in addition to communion wine and yams and sometimes goats, the ones we let stroll around the backyard until Sunday morning. The chickens rushed at the pieces of bread Sisi threw to them, disorderly and enthusiastic. My cousins rushed at Father Amadi's words in the same way. Father Amadi included Jaja and me in the conversation, asking us questions. I knew the questions were meant for both of us because he used the plural "you," unu, rather than the singular, gi, yet I remained silent, grateful for Jaja's answers. He asked where we went to school, what subjects we liked, if we played any sports. When he asked what church we went to in Enugu, Jaja told him. "St. Agnes? I visited there once to say Mass," Father Amadi said. I remembered then, the young visiting priest who had broken into song in the middle of his sermon, whom Papa had said we had to pray for because people like him were trouble for the church. There had been many other visiting priests through the months, but I knew it was him. I just knew. And I remembered the song he had sung.

"Did you?" Aunty Ifeoma asked. "My brother, Eugene, almost single-handedly finances that church. Lovely church."

"Chelukwa. Wait a minute. Your brother is Eugene Achike? The publisher of the Standard?"

"Yes, Eugene is my elder brother. I thought I'd mentioned it before." Aunty Ifeoma's smile did not quite brighten her face.

"Ezi okwu? I didn't know." Father Amadi shook his head. "I hear he's very involved in the editorial decisions. The Standard is the only paper that dares to tell the truth these days."

"Yes," Aunty Ifeoma said. "And he has a brilliant editor, Ade Coker, although I wonder how much longer before they lock him up for good. Even Eugenes money will not buy everything."

"I was reading somewhere that Amnesty World is giving your brother an award," Father Amadi said. He was nodding slowly, admiringly, and I felt myself go warm all over, with pride, with a desire to be associated with Papa. I wanted to say something, to remind this handsome priest that Papa wasn't just Aunty Ifeoma's brother or the Standard's publisher, that he was my father. I wanted some of the cloudlike warmth in Father Amadi's eyes to rub off on me, settle on me.

"An award?" Amaka asked, bright-eyed. "Mom, we should at least buy the Standard once in a while so we'll know what is going on."

"Or we could ask for free copies to be sent to us, if prides were swallowed," Obiora said.

"I didn't even know about the award," Aunty Ifeoma said. "Not that Eugene would tell me anyway, igasikwa. We can't even have a conversation. After all, I had to use a pilgrimage to Aokpe to get him to say yes to the children's visiting us."

"So you plan to go to Aokpe?" Father Amadi asked.

"I was not really planning to. But I suppose we will have to go now, I will find out the next apparition date."

"People are making this whole apparition thing up. Didn't they say Our Lady was appearing at Bishop Shanahan Hospital the other time? And then that she was appearing in Transekulu?" Obiora asked.

"Aokpe is different. It has all the signs of Lourdes," Amaka said. "Besides, it's about time Our Lady came to Africa. Don't you wonder how come she always appears in Europe? She was from the Middle East, after all."

"What is she now, the Political Virgin?" Obiora asked, and I looked at him again. He was a bold, male version of what I could never have been at fourteen, what I still was not.

Father Amadi laughed. "But she's appeared in Egypt, Amaka. At least people flocked there, like they are flocking to Aokpe now. O bugodi, like migrating locusts."

"You don't sound like you believe, Father." Amaka was watching him.

"I don't believe we have to go to Aokpe or anywhere else to find her. She is here, she is within us, leading us to her Son." He spoke so effortlessly, as if his mouth were a musical instrument that just let sound out when touched, when opened.

"But what about the Thomas inside us, Father? The part that needs to see to believe?" Amaka asked. She had that expression that made me wonder if she was serious or not.

Father Amadi did not respond; instead he made a face, and Amaka laughed, the gap between her teeth wider, more angular, than Aunty Ifeoma's, as if someone had pried her two front teeth apart with a metal instrument.

After dinner, we all retired to the living room, and Aunty Ifeoma asked Obiora to turn the TV off so we could pray while Father Amadi was here. Chima had fallen asleep on the sofa, and Obiora leaned against him throughout the rosary. Father Amadi led the first decade, and at the end, he started an Igbo praise song. While they sang, I opened my eyes and stared at the wall, at the picture of the family at Chima's baptism. Next to it was a grainy copy of the pieta, the wooden frame cracked at the corners. I pressed my lips together, biting my lower lip, so my mouth would not join in the singing on its own, so my mouth would not betray me. We put our rosaries away and sat in the living room eating corn and ube and watching Newsline on television. I looked up to find Father Amadi's eyes on me, and suddenly I could not lick the ube flesh from the seed. I could not move my tongue, could not swallow. I was too aware of his eyes, too aware that he was looking at me, watching me.

"I haven't seen you laugh or smile today, Kambili," he said, finally.

I looked down at my corn. I wanted to say I was sorry that I did not smile or laugh, but my words would not come, and for a while even my ears could hear nothing.

"She is shy," Aunty Ifeoma said.

I muttered a word I knew was nonsense and stood up and walked into the bedroom, making sure to close the door that led to the hallway. Father Amadi's musical voice echoed in my ears until I fell asleep.

Laughter always rang out in Aunty Ifeoma's house, and no matter where the laughter came from, it bounced around all the walls, all the rooms. Arguments rose quickly and fell just as quickly. Morning and night prayers were always peppered with songs, Igbo praise songs that usually called for hand clapping. Food had little meat, each person's piece the width of two fingers pressed close together and the length of half a finger. The flat always sparkled-Amaka scrubbed the floors with a stiff brush, Obiora did the sweeping, Chima plumped up the cushions on the chairs. Everybody took turns washing plates. Aunty Ifeoma included Jaja and me in the plate-washing schedule, and after I washed the garri-encrusted lunch plates, Amaka picked them off the tray where I had placed them to dry and soaked them in water. "Is this how you wash plates in your house?" she asked. "Or is plate washing not included in your fancy schedule?"

I stood there, staring at her, wishing Aunty Ifeoma were there to speak for me. Amaka glared at me for a moment longer and then walked away.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)