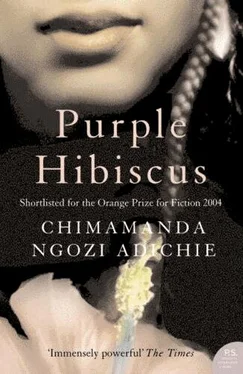

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Amaka!" Obiora shouted.

Aunty Ifeoma came out holding a huge rosary with blue beads and a metal crucifix. Obiora turned off the TV as the credits started to slide down the screen. Obiora and Amaka went to get their rosaries from the bedroom while Jaja and I slipped ours out of our pockets. We knelt next to the cane chairs and Aunty Ifeoma started the first decade. After we said the last Hail Mary, my head snapped back when I heard the raised, melodious voice. Amaka was singing! "Ka m bunie afa gi enu.." Aunty Ifeoma and Obiora joined her, their voices melding. My eyes met Jaja's. His eyes were watery, full of suggestions. No! I told him, with a tight blink. It was not right. You did not break into song in the middle of the rosary. I did not join in the singing, and neither did Jaja. Amaka broke into song at the end of each decade, uplifting Igbo songs that made Aunty Ifeoma sing in echoes, like an opera singer drawing the words from the pit of her stomach.

After the rosary, Aunty Ifeoma asked if we knew any of the songs. "We don't sing at home," Jaja answered.

"We do here," Aunty Ifeoma said, and I wondered if it was irritation that made her lower her eyebrows.

Obiora turned on the TV after Aunty Ifeoma said good night and went into her bedroom. I sat on the sofa, next to Jaja, watching the images on TV, but I couldn't tell the olive-skinned characters apart. I felt as if my shadow were visiting Aunty Ifeoma and her family, while the real me was studying in my room in Enugu, my schedule posted above me. I stood up shortly and went into the bedroom to get ready for bed. Even though I did not have the schedule, I knew what time Papa had penciled in for bed. I fell off to sleep wondering when Amaka would come in, if her lips would turn down at the corners in a sneer when she looked at me sleeping.

I dreamed that Amaka submerged me in a toilet bowl full of greenish-brown lumps. First my head went in, and then the bowl expanded so that my whole body went in, too. Amaka chanted, "Flush, flush, flush," while I struggled to break free. I was still struggling when I woke up. Amaka had rolled out of bed and was knotting her wrapper over her nightdress. "We're going to fetch water at the tap," she said. She did not ask me to come, but I got up, tightened my wrapper, and followed her. Jaja and Obiora were already at the tap in the tiny backyard, old car tires and bicycle parts and broken trunks were piled in a corner. Obiora placed the containers under the tap, aligning the open mouths with the rushing water. Jaja offered to take the first filled container back to the kitchen, but Obiora said not to worry and took it in. While Amaka took the next,]M placed a smaller container under the tap and filled it. He had slept in the living room, he told me, on a mattress that Obiofl unrolled from behind the bedroom door and covered with a wrapper. I listened to him and marveled at the wonder in his voice, at how much lighter the brown of his pupils was. I ofered to carry the next container, but Amaka laughed and said I had soft bones and could not carry it.

When we finished, we said morning prayers in the living room, a string of short prayers punctuated by songs. Aunt Ifeoma prayed for the university, for the lecturers and administration, for Nigeria, and finally, she prayed that we might find peace and laughter today. As we made the sign of the cross, I looked up to seek out Jaja's face, to see if he, too, was bewildered that Aunty Ifeoma and her family prayed for, of all things, laughter. We took turns bathing in the narrow bathroom, with half full buckets of water, warmed for a while with a heating coil plunged into them. The spotless tub had a triangular hole at one corner, and the water groaned like a man in pain as it drained. I lathered over with my own sponge and soap-Mama had carefully packed my toiletries-and although I scooped the water with a shallow cup and poured it slowly over my body, I still felt slippery as I stepped on the old towel placed on the floor.

Aunty Ifeoma was at the dining table when I came out, dissolving a few spoonfuls of dried milk in a jug of cold water. "If I let these children take the milk themselves, it will not last a week," she said, before taking the tin of Carnation dried milk back to the safety of her room. I hoped that Amaka would not ask me if my mother did that, too, because I would stutter if I had to tell her that we took as much creamy Peak milk as we wanted back home.

Breakfast was okpa that Obiora had dashed out to buy from somewhere nearby. I had never had okpa for a meal, only for a snack when we sometimes bought the steam-cooked cowpea-and-palm-oil cakes on the drive to Abba. I watched Amaka and Aunty Ifeoma cut up the moist yellow cake and did the same. Aunty Ifeoma asked us to hurry up. She wanted to show Jaja and me the campus and get back in time to cook. She had invited Father Amadi to dinner.

"Are you sure there's enough fuel in the car, Mom?" Obiora asked.

"Enough to take us around campus, at least. I really hope fuel comes in the next week, otherwise when we resume, I will have to walk to my lectures."

"Or take okada," Amaka said, laughing.

"I will try that soon at this rate."

"What are okada?" Jaja asked.

I turned to stare at him, surpprised. I did not think he would ask that question or any other question.

"Motorcycles," Obiora said. "They have become more popular than taxis."

Aunty Ifeoma stopped to pluck at some browned leaves in the garden as we walked to the car, muttering that the harmattan was killing her plants. Amaka and Obiora groaned and said, "Not the garden now, Mom!"

"That's a hibiscus, isn't it, Aunty?" Jaja asked, staring at a plant close to the barbed wire fencing. "I didn't know there were purple hibiscuses."

Aunty Ifeoma laughed and touched the flower, colored a deep shade of purple that was almost blue. "Everybody has that reaction the first time. My good friend Phillipa is a lecturer in botany. She did a lot of experimental work while she was here. Look, here's white ixora, but it doesn't bloom as fully as the red."

Jaja joined Aunty Ifeoma, while we stood watching them. "O maka, so beautiful," Jaja said. He was running a finger over a flower petal. Aunty Ifeoma's laughter lengthened to a few more syllables.

"Yes, it is. I had to fence my garden because the neighborhood children came in and plucked many of the more unusual flowers. Now I only let in the altar girls from our church or the Protestant church."

"Mom, o zugo. Let's go," Amaka said.

But Aunty Ifeoma spent a little longer showing Jaja her flowers before we piled into the station wagon and she drove off. The street she turned into was steep and she switched the ignition off and let the car roll, loose bolts rattling. "To save fuel," she said, turning briefly to Jaja and me.

The houses we drove past had sunflower hedges, and the palm-size flowers brightened the foliage in big yellow polka dots. The hedges had many gaping holes, so I could see the backyards of the houses-the metal water tanks balanced on unpainted cement blocks, the old tire swings hanging from guava trees, the clothes spread out on lines tied tree to tree. At the end of the street, Aunty Ifeoma turned the ignition on because the road had become level. "That's the university primary school," she said. "That's where Chima goes. It used to be so much better, but now look at all the missing louvers in the windows, look at the dirty buildings."

The wide schoolyard, enclosed by a trimmed whistling pine hedge, was cluttered with long buildings as if they had all sprung up at will, unplanned. Aunty Ifeoma pointed at a building next to the school, the Institute of African Studies, where her office was and where she taught most of her classes. The building was old; I could tell from the color and from the windows, coated with the dust of so many harmattans that they would never shine again. Aunty Ifeoma drove through a roundabout planted with pink periwinkle flowers and lined with bricks painted alternating black and white. On the side of the road, a field stretched out like green bed linen, dotted by mango trees with faded leaves struggling to retain their color against the drying wind. "That's the field where we have our bazaars," Aunty Ifeoma said. "And over there are female hostels. There's Mary Slessor Hall. Over there is Okpara Hall, and this is Bello Hall, the most famous hostel, where Amaka has sworn she will live when she enters the university and launches her activist movements." Amaka laughed but did not dispute Aunty Ifeoma. "Maybe you two will be together, Kambili."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)