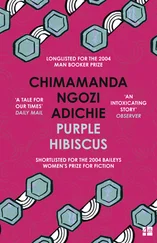

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Let us go, Papa-Nnukwu," Jaja said, finally, rising.

"All right, my son," Papa-Nnukwu said. He did not say "What, so soon?" or "Does my house chase you away?" He was used to our leaving moments after we arrived. When he walked us to the car, balancing on his crooked walking stick made from a tree branch, Kevin came out of the car and greeted him, then handed him a slim wad of cash.

"Oh? Thank Eugene for me," Papa-Nnukwu said, smiling. "Thank him."

He waved as we drove off. I waved back and kept my eyes on him while he shuffled back into his compound. If Papa-Nnukwu minded that his son sent him impersonal, paltry amounts of money through a driver, he didn't show it. He hadn't shown it last Christmas, or the Christmas before. He had never shown it.

It was so different from the way Papa had treated my maternal grandfather until he died five years ago. When we arrived at Abba every Christmas, Papa would stop by Grandfather's house at our ikwu nne, Mother's maiden home, before we even drove to our own compound. Grandfather was very light-skinned, almost albino, and it was said to be one of the reasons the missionaries had liked him. He determinedly spoke English, always, in a heavy Igbo accent. He knew Latin, too, often quoted the articles of Vatican I, and spent most of his time at St. Paul's, where he had been the first catechist. He had insisted that we call him Grandfather, in English, rather than Papa-Nnukwu or Nna-Ochie. Papa still talked about him often, his eyes proud, as if Grandfather were his own father. He opened his eyes before many of our people did, Papa would say; he was one of the few who welcomed the missionaries. Do you know how quickly he learned English? When he became an interpreter, do you know how many converts he helped win? Why, he converted most of Abba himself! He did things the right way, the way the white people did, not what our people do now!

Papa had a photo of Grandfather, in the full regalia of the Knights of St. John, framed in deep mahogany and hung on our wall back in Enugu. I did not need that photo to remember Grandfather, though. I was only ten when he died, but I remembered his almost-green albino eyes, the way he seemed to use the word sinner in every sentence.

"Papa-Nnukwu does not look as healthy as last year," I whispered close to Jaja's ear as we drove off. I did not want Kevin to hear.

"He is an old man," Jaja said.

When we got home, Sisi brought up our lunch, rice and fried beef, on fawn-colored elegant plates, and Jaja and I ate alone. The church council meeting had started, and we heard the male voices rise sometimes in argument, just as we heard the up-down cadence of the female voices in the backyard, the wives of our umunna who were oiling pots to make them easier to wash later and grinding spices in wooden mortars and starting fires underneath the tripods.

"Will you confess it?" I asked Jaja, as we ate.

"What?"

"What you said today, that if we were thirsty, we would drink in Papa-Nnukwu's house. You know we can't drink in Papa-Nnukwu's house," I said.

"I just wanted to say something to make him feel better."

"He takes it well."

"He hides it well," Jaja said.

Papa opened the door then and came in. I had not heard him come up the stairs, and besides, I did not think he would come up because the church council meeting was still going on downstairs.

"Good afternoon, Papa," Jaja and I said.

"Kevin said you stayed up to twenty-five minutes with your grandfather. Is that what I told you?" Papa's voice was low.

"I wasted time, it was my fault," Jaja said.

"What did you do there? Did you eat food sacrificed to idols? Did you desecrate your Christian tongue?"

I sat frozen; I did not know that tongues could be Christian, too. "No," Jaja said.

Papa was walking toward Jaja. He spoke entirely in Igbo now. I thought he would pull at Jaja's ears, that he would tug and yank at the same pace as he spoke, that he would slap Jaja's face and his palm would make that sound, like a heavy book falling from a library shelf in school. And then he would reach across and slap me on the face with the casualness of reaching for the pepper shaker. But he said, "I want you to finish that food and go to your rooms and pray for forgiveness," before turning to go back downstairs.

The silence he left was heavy but comfortable, like a well-worn, prickly cardigan on a bitter morning. "You still have rice on your plate," Jaja said, finally.

I nodded and picked up my fork. Then I heard Papa's raised voice just outside the window and put the fork down.

"What is he doing in my house? What is Anikwenwa doing in my house?" The enraged timber in Papa's voice made my fingers cold at the tips.

Jaja and I dashed to the window, and because we could see nothing, we dashed out to the veranda and stood by the pillars. Papa was standing in the front yard, near an orange tree, screaming at a wrinkled old man in a torn white singlet and a wrapper wound round his waist. A few other men stood around Papa. "What is Anikwenwa doing in my house? What is a worshiper of idols doing in my house? Leave my house!"

"Do you know that I am in your father's age group, gbo?" the old man asked. The finger he waved in the air was meant for Papa's face, but it only hovered around his chest. "Do you know that I sucked my mother's breast when your father sucked his mother's?"

"Leave my house!" Papa pointed at the gate. Two men slowly ushered Anikwenwa out of the compound. He did not resist; he was too old to, anyway. But he kept looking back and throwing words at Papa. "Ifukwa gi! You are like a fly blindly following a corpse into the grave!"

I followed the old man's unsteady gait until he walked out through the gates.

Aunty Ifeoma came the next day, in the evening, when the orange trees started to cast long, wavy shadows across the water fountain in the front yard. Her laughter floated upstairs into the living room, where I sat reading. I had not heard it in two years, but I would know that cackling, hearty sound anywhere. Aunty Ifeoma was as tall as Papa, with a well-proportioned body. She walked fast, like one who knew just where she was going and what she was going to do there. And she spoke the way she walked, as if to get as many words out of her mouth as she could in the shortest time.

"Welcome, Aunty, nno," I said, rising to hug her. She did not give me the usual brief side hug. She clasped me in her arms and held me tightly against the softness of her body. The wide lapels of her blue, A-line dress smelled of lavender. "Kambili, kedu?" A wide smile stretched her dark-complected face, revealing a gap between her front teeth.

"I'm fine, Aunty."

"You have grown so much. Look at you, look at you." She reached out and pulled my left breast. "Look how fast these are growing!"

I looked away and inhaled deeply so that I would not start to stutter. I did not know how to handle that kind of playfulness.

"Where is Jaja?" she asked.

"He's asleep. He has a headache."

"A headache three days to Christmas? No way. I will wake him up and cure that headache." Aunty Ifeoma laughed. "We got here before noon; we left Nsukka really early and would have gotten here sooner if the car didn't break down on the road, but it was near Ninth Mile, thank God, so it was easy finding a mechanic."

"Thanks be to God," I said. Then, after a pause I asked, "How are my cousins?"

It was the polite thing to say; still, I felt strange asking about the cousins I hardly knew.

"They're coming soon. They're with your Papa-Nnukwu, and he had just started one of his stories. You know how he likes to go on and on."

"Oh," I said. I did not know that Papa-Nnukwu liked to go on and on. I did not even know that he told stories.

Mama came in holding a tray piled high with bottles of soft and malt drinks lying on their sides. A plate of chin-chin was balanced on top of the drinks. "Nwunye m, who are those for?" Aunty Ifeoma asked.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)