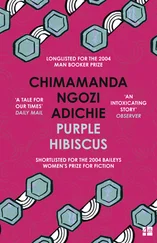

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But it was not only Papa who received visitors; the villagers trooped to every big house with a big gate, and sometimes they took plastic bowls with firm covers. It was Christmas.

Jaja and I were upstairs unpacking when Mama came in and said, "Ade Coker came by with his family to wish us a merry Christmas. They are on their way to Lagos. Come downstair and greet them."

Ade Coker was a small, round, laughing man. Every time I saw him, I tried to imagine him writing those editorials in the Standard; I tried to imagine him defying the soldiers. And I could not. He looked like a stuffed doll, and because he was always smiling, the deep dimples in his pillowy cheeks looked like permanent fixtures, as though someone had sunk a stick into his cheeks. Even his glasses looked dollish: they were thicker than window louvers, tinted a strange bluish shade, and framed in white plastic. He was throwing his baby, a perfectly round copy of himself, in the air when we came in. His little daughter was standing close to him, asking him to throw her in the air, too.

"Jaja, Kambili, how are you?" he said, and before we could reply, he laughed his tinkling laugh and, gesturing to the baby, said, "You know they say the higher you throw them when they're young, the more likely they are to learn how to fly!"

The baby gurgled, showing pink gums, and reached out for his father's glasses. Ade Coker tilted his head back, threw the baby up again. His wife, Yewande, hugged us, asked how we were, then slapped Ade Coker's shoulder playfully and took the baby from him. I watched her and remembered her loud, choking cries to Papa.

"Do you like coming to the village?" Ade Coker asked us.

We looked at Papa at the same time; he was on the sofa, reading a Christmas card and smiling. "Yes," we said.

"Eh? You like coming to this bush place?" His eyes widened theatrically. "Do you have friends here?"

"No," we said.

"So what do you do in this back of beyond, then?" he teased.

Jaja and I smiled and said nothing. "They are always so quiet," he said, turning to Papa. "So quiet."

"They are not like those loud children people are raising these days, with no home training and no fear of God," Papa said, and I was certain that it was pride that stretched Papa's lips and lightened his eyes. "Imagine what the Standard would be if we were all quiet." It was a joke. Ade Coker was laughing; so was his wife, Yewanda. But Papa did not laugh.

Jaja and I turned and went back upstairs, silently.

The rustling of the coconut fronds woke me up. Outside our high gates, I could hear goats bleating and cocks crowing and people yelling greetings across mud compound walls. "Gudu morni. Have you woken up, eh? Did you rise well?" "Gudu morni. Did the people of your house rise well, oh?"*.

I reached out to slide open my bedroom window, to hear they sounds better and to let in the clean air tinged with goat droppings and ripening oranges. Jaja tapped on my door before ha came into my room. Our rooms adjoined; back in Enugu, they were far apart.

"Are you up?" he asked. "Let's go down for prayers before Papa calls us."

I tied my wrapper, which I had used as a light cover in the warm night, over my nightdress, knotted it under my arm, and followed Jaja downstairs.

The wide passages made our house feel like a hotel, as did the impersonal smell of doors kept locked most of the year, of unused bathrooms and kitchens and toilets, of uninhabited rooms. We used only the ground floor and first floor; the other two were last used years ago, when Papa was made a chief and took his omelora title. The members of our umunna had urged him for so long, even when he was still a manager at Leventis and had not bought the first factory, to take a title. He was wealthy enough, they insisted; besides, nobody among our umunna had ever taken a title. So when Papa finally decided to after extensive talks with the parish priest and insisting that all pagan undertones be removed from his title-taking ceremony, it was like a mini New Yam festival. Cars had taken up every inch of the dirt road running through Abba. The third and fourth floors had swarmed with people. Now I went up there only when I wanted to see farther than the road just outside our compound walls.

"Papa is hosting a church council meeting today," Jaja said. "I heard him telling Mama."

"What time is the meeting?"

"Before noon." And with his eyes he said, We can spend time together then. In Abba, Jaja and I had no schedules. We talked more and sat alone in our rooms less, because Papa was too busy entertaining the endless stream of visitors and attending church council meetings at five in the morning and town council meetings until midnight. Or maybe it was because Abba was different, because people strolled into our compound at will, because the very air we breathed moved more slowly.

Papa and Mama were in one of the small living rooms that led off the main living room downstairs. "Good morning, Papa. Good morning, Mama," Jaja and I said.

"How are you both?" Papa asked.

"Fine," we said.

Papa looked bright-eyed; he must have been awake for hours. He was flipping through his Bible, the Catholic version with the deuterocanonical books, bound in shiny black leather. Mama looked sleepy. She rubbed her crusty eyes as she asked if we had slept well.

I could hear voices from the main living room. Guests arrived with dawn here. When we had made the sign of the cross and gotten down on our knees, around the table, someone knocked on the door. A middle-aged man in a threadbare T-shirt peeked in.

"Omelora!" the man said in the forceful tone people used when they called others by their titles. "I am leaving now. I want to see if I can buy a few Christmas things for my children at Oye Abagana." He spoke English with an Igbo accent so strong it decorated even the shortest words with extra vowels. Papa liked it when the villagers made an effort to speak English around him. He said it showed they had good sense.

"Ogbunambala!" Papa said. "Wait for me, I am praying with my family. I want to give you a little something for the children. You will also share my tea and bread with me."

"Hei! Omelora! Thank sir. I have not drank milk this year!"

The man still hovered at the door. Perhaps he imagined that leaving would make Papa's promise of tea with milk disappear.

"Ogbunambala! Go and sit down and wait for me."

The man retreated. Papa read from the psalms before saying the Our Father, the Hail Mary, the Glory Be, and the Apostles Creed. Although we spoke aloud after Papa said the first few words alone, an outer silence enveloped us all, shrouding us. But when he said, "We will now pray to the spirit in our own words, for the spirit intercedes for us in accordance with His will," the silence was broken. Our voices sounded loud, discordant. Mama started with a prayer for peace and for the rulers of our country. Jaja prayed for priests and for the religious. I prayed for the Pope. Finally, for twenty minutes, Papa prayed for our protection from ungodly people and forces, for Nigeria and the Godless men ruling it, and for us to continue to grow in righteousness. Finally, he prayed for the conversion of our Papa-Nnukwu, so that Papa-Nnukwu would be saved from hell. Papa spent some time describing hell, as if God did not know that the flames were eternal and raging and fierce. At the end we raised our voices and said, "Amen!"

Papa closed the Bible. "Kambili and Jaja, you will go this afternoon to your grandfather's house and greet him. Kevin will take you. Remember, don't touch any food, don't drink anything. And, as usual, you will stay not longer than fifteen minutes. Fifteen minutes."

"Yes, Papa." We had heard this every Christmas for the past few years, ever since we had started to visit Papa-Nnukwu. Papa-Nnukwu had called an umunna meeting to complain to the extended family that he did not know his grandchildren and that we did not know him. Papa-Nnukwu had told Jaja and me this, as Papa did not tell us such things. Papa-Nnukwu had told the umunna how Papa had offered to build him a house, buy him a car, and hire him a driver, as long as he converted and threw away the chi in the thatch shrine in his yard. Papa-Nnukwu laughed and said he simply wanted to see his grandchildren when he could. He would not throw away his chi; he had already told Papa this many times. The members of our umunna sided with Papa, they always did, but they urged him to let us visit Papa-Nnukwu, to greet him, because every man who was old enough to be called grandfather deserved to be greeted by his grandchildren. Papa himself never greeted 1111 Papa-Nnukwu, never visited him, but he sent slim wads of naira through Kevin or through one of our umunna members, slimmer wads than he gave Kevin as a Christmas bonus.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)