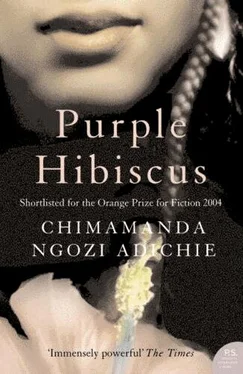

Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Чимаманда Адичи - Purple hibiscus» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2003, ISBN: 2003, Издательство: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Purple hibiscus

- Автор:

- Издательство:Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

- Жанр:

- Год:2003

- ISBN:1-56512-387-5

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Purple hibiscus: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Purple hibiscus»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Purple hibiscus — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Purple hibiscus», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Fine."

"Did you travel abroad?"

"No," I said. I didn't know what else to say, but I wanted Ezinne to know that I appreciated that she was always nice to me even though I was awkward and tongue-tied. I wanted to say thank you for not laughing at me and calling me a "backyard snob" the way the rest of the girls did, but the words that came out were, "Did you travel?"

Ezinne laughed. "Me? O di egivu. It's people like you and Gabriella and Chinwe who travel, people with rich parents. I just went to the village to visit my grandmother."

"Oh," I said.

"Why did your father come this morning?"

"I… I…" I stopped to take a breath because I knew I would stutter even more if I didn't. "He wanted to see my class."

"You look a lot like him. I mean, you're not big, but the features and the complexion are the same," Ezinne said.

"Yes."

"I heard Chinwe took the first position from you last term. Abi?"

I remained a backyard snob to most of my class girls until the end of term. But I did not worry too much about that because I carried a bigger load — the worry of making sure I came first this term. It was like balancing a sack of gravel on my head every day at school and not being allowed to steady it with my hand. I still saw the print in my textbooks as a red blur, still saw my baby brother's spirit strung together by narrow lines of blood. I memorized what the teachers said because I knew my textbooks would not make sense if I tried to study later. After every test, a tough lump like poorly made fufu formed in my throat and stayed there until our exercise books came back.

School closed for Christmas break in early December. I peered into my report card while Kevin was driving me home and saw 1/25, written in a hand so slanted I had to study it to make sure it was not 7/25. That night, I fell asleep hugging close the image of Papas face lit up, the sound of Papa's voice telling me how proud of me he was, how I had fulfilled God's purpose for me.

Dust-laden winds of harmattan came with December. They brought the scent of the Sahara and Christmas, and yanked the slender, ovate leaves down from the frangipani and the needlelike leaves from the whistling pines, covering everything in a film of brown. We spent every Christmas in our hometown. Sister Veronica called it the yearly migration of the Igbo. She did not understand, she said in that Irish accent that rolled her words across her tongue, why many Igbo people built huge houses in their hometowns, where they spent only a week or two in December, yet were content to live in cramped quarters in the city the rest of the year. I often wondered why Sister Veronica needed to understand it, when it was simply the way things were done. The morning winds were swift on the day we left, pulling and pushing the whistling pine trees so that they bent and twisted, as if bowing to a dusty god, their leaves and branches making the same sound as a football referee's whistle. The cars were parked in the driveway, doors and boots open, waiting to be loaded. Papa would drive the Mercedes, with Mama in the front seat and Jaja and me in the back. Kevin would drive the factory car behind us with Sisi, and the factory driver, Sunday, who usually stood in when Kevin took his yearly one-week leave, would drive the Volvo. Papa stood by the hibiscuses, giving directions, one hand sunk in the pocket of his white tunic while the other pointed from item to car. "The suitcases go in the Mercedes, and those vegetables also. The yams will go in the Peugeot 505, with the! cases of Remy Martin and cartons of juice. See if the stacks of okporoko will fit in, too. The bags of rice and garri and beans; and the plantains go in the Volvo."

There was a lot to pack, and Adamu came over from the gate to help Sunday and Kevin. The yams alone, wide tube the size of young puppies, filled the boot of the Peugeot 505 and even the front seat of the Volvo had a bag of beans slanting across it, like a passenger who had fallen asleep.

Kevin and Sunday drove off first, and we followed, so that if the soldiers at the roadblocks stopped them, he would see and stop, too. Papa started the rosary before we drove out of our gate street. He stopped at the end of the first decade so Mama could continue with the next set of ten Hail Marys. Jaja led the next decade; then it was my turn.

Papa took his time driving. The expressway was a single lane, and when we got behind a lorry he stayed put, muttering that the roads were unsafe, that the people in Abuja had stolen all the money meant for making the expressways dual-carriage. Many cars horned and overtook us, and some were so full of Christmas yams and bags of rice and crates of soft drinks that their boots almost grazed the road.

At Ninth Mile, Papa stopped to buy bread and okpa. Hawkers descended on our car, pushing boiled eggs, roasted cashew nuts, bottled water, bread, okpa, agidi into every window the car, chanting: "Buy from me, oh, I will sell well to you." "Look at me, I am the one you are looking for." Although Papa bought only bread and okpa wrapped in banana leaves, he gave a twenty-naira note to each of the other hawkers, and their "Thank sir, God bless you" chants echoed in my ear as we drove off and approached Abba.

The green welcome to abba town sign that led off the expressway would have been easy to miss because it was so small. Papa turned onto the dirt road, and soon I heard the screech-screech-screech of the low underbelly of the Mercedes scraping the bumpy, sun-baked dirt road. As we drove past, people waved and called out Papa's title: "Omelora!" Mud and thatch huts stood close to three-story houses that nestled behind ornate metal gates. Naked and seminaked children played with limp footballs. Men sat on benches beneath trees, drinking palm wine from cow horns and cloudy glass mugs.

The car was coated in dust by the time we got to the wide black gates of our country home. Three elderly men standing under the lone ukwa tree near our gates waved and shouted, "Nno nu! Nno nu! Have you come back? We will come in soon to say welcome!"

Our gateman threw the gates open. "Thank you, Lord, for journey mercies," Papa said as he drove into the compound, crossing himself.

"Amen," we said. Our house still took my breath away, the four-story white majesty of it, with the spurting fountain in front and the coconut trees flanking it on both sides and the orange trees dotting the front yard.

Three little boys rushed into the compound to greet Papa. They had been chasing our cars down the dirt road. "Omelora! Good afun, sah!" they chorused. They wore only shorts, and each one's belly button was the size of a small balloon. "Kedu nu?" Papa gave them each ten naira from a wad of notes he pulled out of his hold-all. "Greet your parents, make sure you show them this money."

"Yes sah! Tank sah!" They dashed out of the compound, laughing loudly.

Kevin and Sunday unpacked the foodstuffs while Jaja and I unpacked the suitcases from the Mercedes. Mama went to the backyard with Sisi to put away the cast iron cooking tripods. Our food would be cooked on the gas cooker inside the kitchen, but the metal tripods would balance the big pots that would cook rice and stews and soups for visitors. Some of the pots were big enough to fit a whole goat. Mama and Sisi hardly did any of that cooking; they simply stayed around and provided more salt, more Maggi cubes, more utensils, because the wives of the members of our umunna came over to do the cooking. They wanted Mama to rest, they said, after the stress of the city. And every year they took the leftovers-the fat pieces of meat, the rice and beans, the bottles of soft drink and maltii and beer-home with them afterward. We were always prepared to feed the whole village at Christmas, always prepared so that none of the people who came in would leave without eating and drinking to what Papa called a reasonable level of satisfaction. Papa's title was omelora, after all, The One Who Does for the Community.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Purple hibiscus» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Purple hibiscus» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![О Генри - Пурпурное платье [The Purple Dress]](/books/405339/o-genri-purpurnoe-plate-the-purple-dress-thumb.webp)